People are the subject of archaeology, and artifacts — the items produced by people in the past — are the means by which archaeologists learn about them. Pottery fragments and other artifacts remind us of the long history of life along the Gulf Coast — a history that stretches back over ten thousand years. The Indigenous People of the Gulf Coast and Mobile-Tensaw Delta manufactured a number of artifacts ranging from the enormous (earthen mounds) to the minute (shell beads). No single item can fully represent thousands of years or the ancestors of modern Choctaw, Creek and Seminole people. This broken piece of pottery, however, has the potential to weave a rich story of the owners’ lives: when and where they lived, what kinds of meals they cooked and ate, the nature of trade and interactions with other groups and even religious beliefs. This fragment of pottery is a piece of a much larger ceramic vessel, perhaps a bowl or bottle, and its physical features along with the context in which it was found have much to tell us about the people who made and used it.

Chronology

The first pottery made by people in the Mobile region dates to about 1400 B.C., but in fact, Native American people have lived here for much longer than that — over ten thousand years. Stone tools, pottery vessels and other artifacts changed over time as people invented new technologies and styles of decoration went in and out of fashion. We know from its shape and incised decoration that this pottery fragment dates to c. A.D. 1200 – 1550, what archaeologists call the Bottle Creek phase of the Pensacola culture. The early archaeologists who named this culture “Pensacola” did not realize that the cultural epicenter was actually in and around Mobile Bay. We now know that the people who made this pottery also built the large earthen mounds at the Bottle Creek site on Mound Island, as well as many of the shell mounds that are so common along Mobile Bay.

Function

Archaeologists can study how people used pottery based on the technological choices the potters made. Those in the Pensacola culture were farmers who grew corn (in addition to fishing, hunting and gathering wild foods), and their pottery reflects the fact that the corn they grew had to be cooked at boiling temperatures for long periods of time before it could be eaten. Pensacola pottery is made from local clay that has been tempered with crushed mussel shell. Potters understood that mussel shell improves the workability of clay as well as the thermal properties of the finished pot. When heated, shell expands at the same rate as clay, which means that shell-tempered pots are well suited to cooking corn and dishes made from it. This fragment of pottery is likely a serving vessel rather than a cooking pot, based on its shape and decoration, as well as the fact that its shell temper is so finely crushed.

Interaction and Trade

Archaeologists describe the Mobile area as a “fulcrum of cultural interaction,” with local people influencing and being influenced by their connections with the coastal people of present-day Louisiana, Mississippi, and Florida, as well as those living in the interior of what is now west-central Alabama and the Lower Mississippi Valley. Pottery tells us a particular story about that interaction. If you look closely at the design incised on the pottery fragment, you may make out the outlines of a hand held horizontally, with short vertical lines marking the finger joints and a circle incised on the palm. This design, called the “hand-and-eye” motif by archaeologists, was a very common design element of art from Moundville, near present-day Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Around A.D. 1200, people from Moundville or nearby moved into the Mobile area, probably to acquire salt from the salt springs in southern Clarke County and conch shells from the Gulf of Mexico, both valued trade items. One result of their interaction with local people was a new pottery tradition that incorporated shell temper as well as new decorative motifs such as the hand-and-eye design. The Pensacola people made this design their own, as the horizontal orientation of the hand is a Gulf Coast innovation.

Ideology

The hand-and-eye motif is also of interest to archaeologists because it relates to the worldview of Pensacola people. Collaborations with art historians and modern Native American religious practitioners have shown that the hand-and-eye motif represents the constellation known today as Orion. Pensacola and other Mississippian people believed that when Orion touched the western horizon, from late November to late April, a portal opened — here represented by the circle on the palm of the hand — allowing those who had passed on in the preceding months to enter the Milky Way or “Path of Souls,” upon which they traveled to their final resting place.

One item of material culture opens a world of information about people in the past. Exploring the variety of artifacts in their contexts provides archaeologists with a more complete understanding of the past. The Indigenous People of the Gulf Coast settled this area over ten thousand years ago and developed a complex lifeway and rich traditions in the environment of which they were a part. When Spanish, French and other European people colonized the new world, Native lifeways were disrupted in devastating ways. And yet, they were active participants in the forging of a new multicultural society. Since its founding by the French in 1702, Mobile has been an important center of trade and commerce between people of Native, European and African descent, but the rich cultural history of this area stretches back for millennia.

Philip J. Carr, Ph.D., is a professor of anthropology and Chief Calvin McGhee Endowed Professor of Native American Studies at the University of South Alabama. He is director of the USA Center for Archaeological Studies and Archaeology Museum.

Erin S. Nelson, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of anthropology at the University of South Alabama and is the author of “Authority, Autonomy, and the Archaeology of a Mississippian Community” (2020).

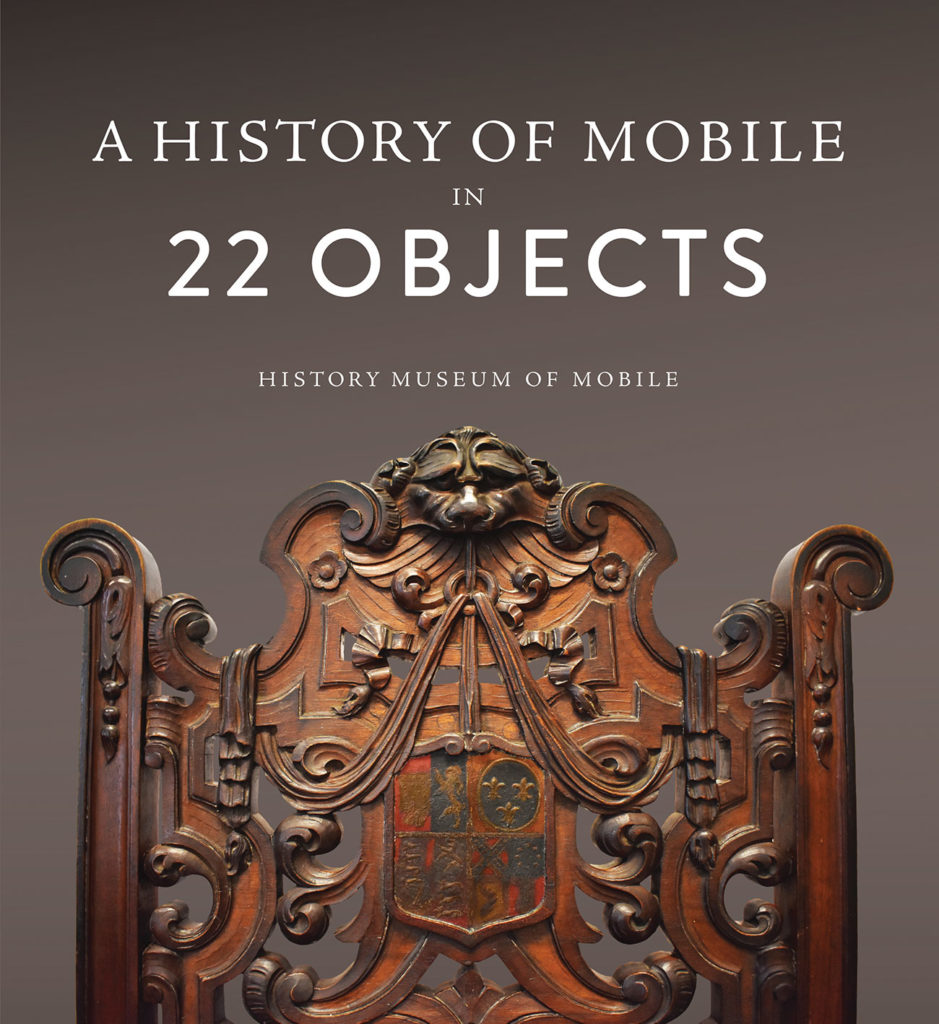

“A History of Mobile in 22 Objects” by various authors.

Click here to purchase

Released in conjunction with the History Museum of Mobile exhibit, this photo-heavy compendium delves into the city’s history through the analysis of 22 artifacts by Mobile’s leading researchers.