For all the delights of my first trip to New York City in 1964, the summer I turned 11, none was greater than having my big sister, Sherrell, show me the town. Fifteen years older than me, my Alabama sister was already a savvy New Yorker, on the first rung of a television career that would eventually lead to being a director. As she walked me down colorful avenues, got us tickets to a Yankees game and took me to the ’64 World’s Fair, at age 26 she was, to me, already a star.

She had a romantic aura, in my mind. As the eldest of four, Sherrell had departed for Sophie Newcomb College at Tulane University when I was still in preschool. On visits home to Mobile, she was the mysterious sibling whose bedroom was at the top of the stairs. While she enjoyed activities I understood, like fishing from a Mobile Bay dock and riding horses, she was also enamored of the stage. Already a veteran of Murphy High theater under the direction of Lois Jean Delaney, with a turn at the Joe Jefferson Players, she was a drama major at Newcomb and loved to sing, filling our house with Rodgers and Hammerstein.

For many girls graduating from college with her, Sherrell later explained to me, a B.A. meant an “MRS” was not far behind. She had suitors, but her heart was drawn to Manhattan. With AEPhi sorority sisters Dianne Orkin, from Jackson, Miss., and Marilyn Meyer, from New Orleans, she headed north. They found a one bedroom on the Upper East Side, set up three beds, and took jobs as receptionists and clerks. They explored the city, went on dates, discovered performers – Sherrell wrote home about a wonderful new singer, Barbra Streisand – and became, in the parlance of the day, “career girls.”

|

While she gloried in theater – letters home were filled with the excitement of seeing new shows like “West Side Story” and “Fiddler on the Roof” – she did not aspire to the footlights.

Her ambition, a heady one then, was to be an independent woman.

She went to Broadway’s “Gypsy” and heard Ethel Merman belt out a song that struck a chord with her: “Some people can get a thrill/ knitting sweaters and sitting still/ That’s OK for some people/ who don’t know they’re alive.”

It was free-flowing big city life — not the world of “some humdrum people” as Merman sang — that brimmed with promise.

She had one lone showbiz contact — a family friend in Mobile, Jimmy Oppenheimer, whose export company she’d worked for one summer, knew someone in TV in New York — but that was it.

Sherrell found a job answering fan mail for “The Garry Moore Show” on CBS. Moore also moderated a quiz show, “I’ve Got a Secret.”

In 1962, “The Garry Moore Show” won an Emmy for Best Variety Show – his young comedienne Carol Burnett received the Emmy for Best Entertainer – and Moore invited each crew member to walk by the camera and offer a salute. In Mobile, we watched in amazement and cheered as Sherrell, in heels and a dress, dark hair cut short, crossed our black-and-white TV screen and gave a big wave.

On my 1964 visit, she took me backstage at “I’ve Got a Secret.” I was fascinated by the TV cameras, the control room monitors and Garry Moore himself: a man only a few inches taller than me, with a flattop and bow tie, who greeted Sherrell warmly and said hello to me and shook my hand.

As we headed back into the New York night, Sherrell was more than a big sister singing at the top of the stairs. She had opened the door to an exotic new world.

From the Deep South in the 1960s, New York City seemed a far cry away. We knew it was avant-garde from the movie “Breakfast at Tiffany’s, ” dangerous from the TV cop show, “Naked City, ” and offbeat from the sitcom, “The Honeymooners.”

Our dad, a prominent attorney who’d become president of the Mobile Bar Association in 1971, was worried about his daughter’s well-being in the vast and menacing “sidewalk jungle.”

|

Although she was 1, 200 miles from home, Sherrell stayed close, writing often.

I have a box of letters to our family in the mid-1960s, telling of entertainers she met, the opera, Central Park, snow and life in an apartment. She and her Newcomb friends had branched out in different directions, and her new roommate was a TWA stewardess, which intrigued my adolescent imagination to no end.

She gave us behind-the-scenes peeks at TV productions as her career

unfolded at variety shows, a popular format of the era.

“Dear Family, ” she wrote on Sept. 25, 1964, after Garry Moore was canceled and she signed on with Carol Burnett’s “The Entertainers, ” “Today is the big day in our office … we air our first show tonight, and you can’t help but feel the excitement and tension in the air.”

When Carol Burnett started a new show on the West Coast, Sherrell got on with a TV country-Western variety hour in New York: “The Jimmy Dean Show.”

“Dear Family, ” she wrote on March 28, 1965, “Jimmy Dean walks around, even on Fifth Avenue, in boots and a cowboy hat and jeans. He is very personable and friendly … There are more Southerners working here than any other place I’ve worked. Maybe I’ll be able to get back some of my accent.”

At “Jimmy Dean” she was secretary to the director, Hal Gurnee, who became her mentor. She also became friends with the show’s music coordinator, a stand-up bass player and former RCA Victor executive, Charles Randolph Grean. Sherrell and Charlie began dating, and she helped him out at Dot Records between TV gigs.

“Dear Family, ” she wrote on Feb. 9, 1967, “I’ve really been having fun, adding my two cents worth to some album ideas that Charlie’s been working on. Roy, perhaps you’ve seen a TV show called ‘Star Trek, ’ which is on Thursday night. There’s a man on there, Leonard Nimoy, who plays a character called Mr. Spock. Well, the album will be ‘Mr. Spock Presents Music From Outer Space.’”

|

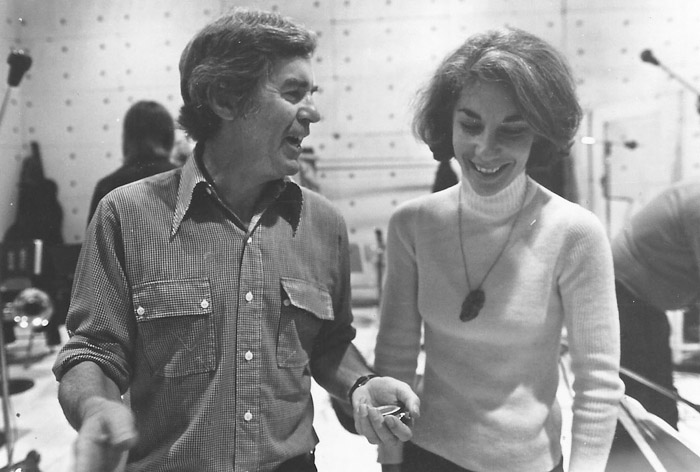

The next year, Sherrell became assistant director at “The David Frost Show, ” with Gurnee as director. She took me to see a David Frost interview when I visited while I was in high school. In the TV world, there were still few women behind the scenes.

In a photo of the 26-person “David Frost” crew that she kept on her wall, she was the only woman.

At “Jack Paar Tonight” in 1972, a return to prime time for the famous talk show host, Sherrell graduated to associate director under Gurnee. She got to work with Charlie again, too – the show’s bandleader – now as husband and wife.

At the dawn of the 1970s, a new soap opera, “All My Children, ” captivated the American scene, and by the mid-1970s, Sherrell became one of its directors. It was “a very big deal, ” as Gurnee said.

In rotation with three others, Sherrell took her turn in charge of the daily drama, a fast-paced schedule with demanding hours. She admired the actors who gave life to the passions and travails of fictional Pine Valley, including Ruth Warwick as Phoebe Tyler, James Mitchell as Palmer Cortlandt, Kim Delaney as Jenny Gardner, and Susan Lucci, whose character Erica Kane became a pop culture icon.

When I graduated from Tulane in 1975, I moved to New York, at first bunking with Sherrell, Charlie and their newborn, Aaron. I watched Sherrell work up close.

She would sit for hours on end with her “All My Children” scripts, making notes, readying scenes in order to work with the crew and the performers.

A day at the studio exhilarated her.

“Being a television director, ” said Gurnee, who went on to direct “Late Show With David Letterman, ” “is like being a fighter pilot: You have so little time to get so much done. Sherrell was always the calm center of things, and she had strength. She had a sense of humor, too, to get through days of tension and complexity.”

Also recalling her “delightful sense of humor, ” Susan Lucci described Sherrell to me as “a spectacular combination of talent, capability, warmth and a dose of Southern charm! I truly always looked forward to the days Sherrell would be directing. I knew I could count on her for wonderful direction and a lot of heart.”

Sherrell received six Daytime Emmy nominations for Outstanding Direction for a Drama Series for “All My Children, ” and one for “Guiding Light.”

For the “All My Children” nominations of 1981, ’82, and ’83, she was the only woman on the directing team.

|

Moving among the glamorous, she was still a Gulf Coast girl, humble, down-to-earth, letting her hair go silver, most at home in old jeans and a sweater.

If Sherrell was in an early wave of women working in television, she was also a pioneer in our family. From growing up in Mobile, to college in New Orleans, to a stint in New York – we followed similar paths.

With Sherrell’s inspiration, our sister Robbie hit the Manhattan stage for a while as a dancer; our sister Becky eventually became a New York City tour guide. When the next generation struck out for the big city, Sherrell’s pull-out sofa was the first stop.

My mother always enjoyed visits to Manhattan, and my dad finally became a fan of the city, too. When Sherrell incorporated them in an “All My Children” scene with nonspeaking, walk-on roles – the character Phoebe, using my mom’s real name, said, “Hello, Evelyn” – they became instantly famous in Mobile.

After retiring from television, Sherrell became licensed as a therapeutic riding instructor. With a zeal for helping special needs students, including her son who dealt with autism, she taught adaptive horseback riding. The process in part, I learned from her, helps those with physical and developmental challenges improve focus, self-confidence and strength, and know the joys of befriending a big, gentle animal.

She had weathered breast cancer at age 50, hardly skipping a beat at work. When cancer impacted her in other ways nearly 20 years later, she could not hold on.

We lost her in 2008, at age 70.

Whenever I’m visiting New York and pass the former studio of “All My Children” on the Upper West Side, I remember a particular day in the 1980s. I was waiting for Sherrell to exit the studio – we had a dinner date – and as soap stars headed out the door, fans came swarming.

Sherrell appeared, buoyant, smiling, her silver hair flowing, and gave me a hug. As we set off down the street, looking for just the right restaurant to share a meal and catch up, I realized that the 15 years difference between us was nothing now. We had started our New York years as little brother and big sister. Now we were closest of friends.

Roy Hoffman, who lives in Fairhope, is the author of five books, including the nonfiction “Alabama Afternoons, ” and the novel, “Chicken Dreaming Corn, ” set in downtown Mobile of the early 1900s. His new novel, “Come Landfall” (University of Alabama Press, Spring 2014), follows three women on the contemporary Gulf Coast whose lives, and loves, are impacted by far-off wars brought home. Contact: [email protected], or Facebook.com/RoyHoffmanWriter (A version of this essay also appeared in “Tulane Magazine.”)

text by Roy Hoffman • photos courtesy of the hoffman family