At the turn of the 20th century, more than three million immigrants from countries all over the world gained American citizenship. Ready for a new start, they embraced the opportunity to become anything they wanted to be. Erik Pederson Overboe, who later changed his name to Erik Overbey, came to Mobile in 1901. Overbey’s work utilized the utilitarian and artistic aspect of photography, making the commonplace seem extraordinary.

Mobile reflected nationwide changes and advancements. The establishment of the Union Depot, the Alabama Dry Dock and Shipbuilding Company, as well as services for the community, such as the Mobile Public Library and the Saenger Theatre, aided the Port City in meeting the needs of its growing population. Overbey saw these changes and decided to document them.

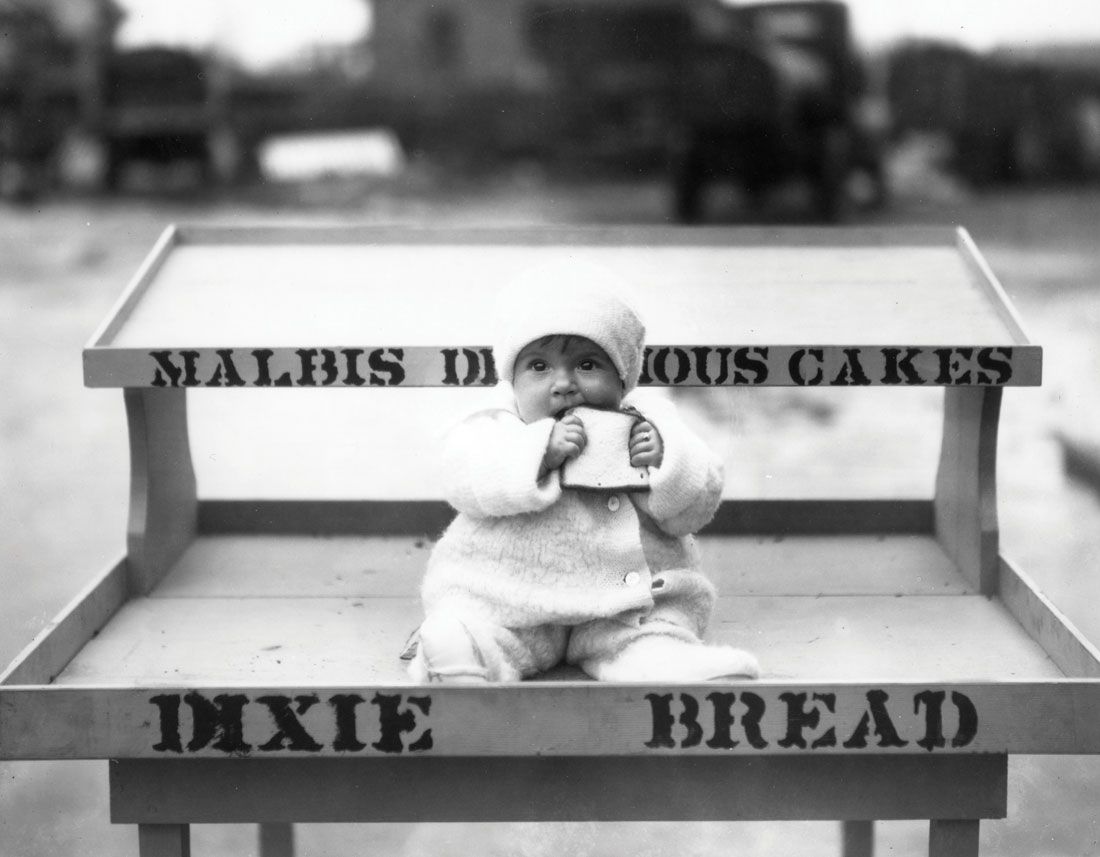

In 1906, Overbey took a leap of faith, invested in an 8-by-10 camera and used his talents to document 20th-century Mobile. He captured images of Dauphin, Royal and Conti streets with people going about their daily lives. He photographed dock workers hauling in fish to sell at the markets. He captured the Mardi Gras kings and queens in their finest garb and ladies donning their traditional bathing suits at the beach. Overbey photographed everything that happened in the city, such as the laying of the cornerstone of the Scottish Rite Temple, and became the chronicler of Mobile from 1906 to 1957.

He did not originally plan to be a photographer when he came to America from Hafslo, Sogn, Norway in 1901. He brought with him his skills as a tailor, not a photographer. Once settled down in Mobile, Overbey worked for John J. Tvedt, a tailor who was the owner of Metropolitan Dye Works.

Why he decided to make a drastic career change is unclear, but with little experience and a desire to learn, he left the only profession he knew and became a professional photographer. According to the Encyclopedia of Alabama, “He joined his fellow Norwegian, P.E. Johnson, who had some photography experience, in opening Johnson and Overbey Photographers. The young immigrant found his partner knew little about photography, however, so he had to teach himself, even as he learned the language and customs of his new home.”

Overbey’s decision to become a photographer was not without merit. There was an increasing number of photographers taking pictures outside the controlled environment of a studio. The ability to take equipment to various locations opened the door to commercial photography. The formats used included single images, stereographs, lantern slides and, in a very popular format, picture postcards.

While Overbey and his partner competed with 50 other studios in Mobile, his talent was obvious, and they quickly dominated the market. According to the book “Shot in Alabama” by Frances Robb, “His most impressive works are large panorama — some are five feet across — that epitomize the increasing importance of outdoor views and the availability of special equipment … Overbey depicted Mobile’s workplaces as symbols of progress, and he developed a telling eye for the viewpoints and details that would fulfill his clients’ needs.”

Overbey’s business quickly grew as he acquired a large collection of plate negatives belonging to W.A. Reed, and he began dedicating long days and nights to the profession that he so loved. As his business matured, he also hired Ernest Horton as his assistant. Horton would work for Overbey from 1918 to 1940.

Overbey was not picky in regards to what needed to be photographed, using his artistic style in all subjects, whether it was portraitures, ships in Mobile Bay or the city’s growing industrial establishments. He also shot for the Mobile Register. Within 10 years, Overbey became the premier local photographer.

He married Ida Cornelia Schiemann, a Mobile native, and they had three children. She passed away in 1944, 33 years before his own death.

Overbey continued working until a health condition prevented it. “He developed cataracts and had difficulty using his old-fashioned view cameras after eye surgery,” wrote Michael Thomason for the Encyclopedia of Alabama. “He retired in 1957 and sold his business to Frances White, who had worked for him for many years.” She sold the negatives to the Mobile Public Library in 1965, and in 1978, the Mobile Public Library transferred the collection to the University of South Alabama. Overbey died in 1977, at age 96.

The Erik Overbey Collection now resides in the Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library. The archives also includes the Horton Collection, which documents his African-American family and neighborhood. Call 341-3900 and schedule an appointment to view the images, or go online here.