Today, Mobile boasts the state’s largest school district, and in fact, it was the first public education system in Alabama. Since its beginnings, it has shared in many of the difficulties that public education as a whole has faced throughout the state. The legislature, led by Mobile Rep. Willoughby Barton, chartered its Board of School Commissioners in 1826, just seven years after Alabama became a state. However, no money was appropriated to support the new creation, and it wasn’t until 1836 that the board began building Barton Academy, financed by a lottery which raised $50, 000, a loan of $15, 000 from the City of Mobile and donations from private individuals such as Henry Hitchcock, perhaps the wealthiest person in Mobile at that time.

The resulting landmark structure, which was named in honor of Rep. Barton, cost more to build than estimated, and when completed, the roof leaked. The board, having no money left to run a public school, rented the building out to various private schools. After a little more than a decade, they decided to sell it and no longer pursue public education. However, when they proposed this to Mobile’s voters, the people soundly rejected it. In the next election, the old board members were turned out and a new group elected, made up of members who were fully committed to a free public education. Taxes were raised to fund the project, and in 1852, Barton opened as a school for all levels of public education. Two years later, the Alabama Legislature accepted the Mobile model for public education statewide. Mobile’s system was based on that of New York and was very progressive in a way, but it was only for whites at that time.

At the end of the 1800s, a few all-black schools were established to satisfy the Supreme Court’s decision that segregation was acceptable so long as facilities provided to both races were “separate but equal.” Despite its rigid segregation, Mobile was a leader in the education of black students. At least they had access to education through the high school level, when only Birmingham and Tuskegee offered such opportunities elsewhere in Alabama. Those high schools were “training schools” loosely based on Booker T. Washington’s model, but in the Port City, Mobile County Training School went far beyond that type of education, achieving accreditation from the Southern Association in the 1930s. It was one of the few black high schools in the South to do so. The institution’s outstanding education was due largely to the leadership of its long-serving principal Dr. Benjamin F. Baker and the support he received from the black community.

Over the decades, public education in Mobile has benefited from such dedicated individuals as Baker who put their students ahead of everything else, in good times and bad, and unfortunately, there have been more of the latter. After only nine years of existence, the public education system was shut down due to the Civil War, and it did not resume operations until after the conflict’s end. Mobile’s economy was in shambles, and tax returns for education reflected that fact.

Not until the turn of the century did Mobile add public schools such as Leinkauf Elementary. It opened in 1903 and was named for William Leinkauf (1827 – 1901), a prominent banker who had been elected to the school board first in 1865 and later served as its president from 1898 until his death. Schools built for black children in the era were named for prominent black educators such as Booker T. Washington. (The Orange Grove School was renamed for him.) Many of these schools were eventually closed, either because of antiquated facilities, changes brought on by integration in the 1960s and ’70s and the city’s population shift westward. Russell School on South Broad Street, Old Shell Road School and Raphael Semmes School on Springhill Avenue are prime examples of defunct school buildings that are still standing.

|

A Changing Society

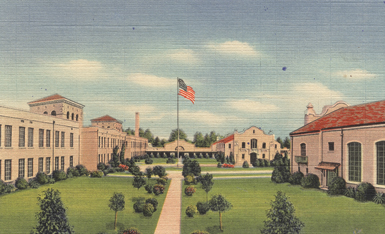

World War I changed Mobile, and those alterations would prove to be more far-reaching in World War II. In both wars, Mobile city and county populations grew rapidly, and the years after both wars would see several new schools open. During World War II, the influx of people here (largely due to war support jobs at Brookley Field) even forced schools to go on split shifts. Half of the students came before noon and the other half after, so that a school could serve twice as many pupils. It was an emergency wartime measure. Moreover, after the Great War, returning soldiers wanted to complete educations interrupted by military service or war work. There were so many new students that Barton, still the only public high school for whites at that time, was inundated. The school board, led by superintendent Samuel S. Murphy (1865 – 1926), rose to the challenge in 1922 and built a new facility, a Spanish Revival structure on the city’s western border. In 1927, two years after it opened its doors, the school was named for S.S. Murphy. Once nicknamed “The Million Dollar High School, ” in recognition of its construction cost, Murphy has been the flagship of Mobile County’s public schools since it opened. Despite the high school’s protracted battles over integration and damage by hurricanes and last year’s Christmas tornado, it remains an educational standout. Many outstanding teachers have made Murphy what it is, educators like “Miss Fitz, ” Lois Jean Fitzsimmons Delaney, who was the drama department there for decades after World War II. (The school’s auditorium is dedicated in her honor.)

Modern-Day Assessments

Schools reflect the communities they serve, including their problems and also their hopes. Mobile County’s Public School System faces the challenges of neighboring cities breaking away to establish their own school systems and the competition of private and parochial schools. The ever-changing expectations for educators and school systems and the shortage of tax revenue to support them are perpetually contentious issues. On top of all this, there is the explosion of paperwork, the rise of standardized testing and the oversight, guidelines and supervision of the state and federal governments.

There are also positive developments over the past few decades. The University of South Alabama, with its large department of education, trains new teachers and updates veteran educators. Other colleges and universities, both local and statewide, have also helped better prepare our teachers. The explosion of computer-based learning and instruction is revolutionizing education at all levels. By and large, the students take naturally to the electronic age, but many teachers must learn how to use these new and evolving tools.

Recently, the school system has seen improvement in its funding resources, thanks largely to a tax increase voters approved a few years ago — the first in half a century. And, the good news is that although new businesses may receive tax breaks to attract them to locate here, that does not include an abatement of taxes for education. High-tech employers, such as Austal and Airbus, want to be able to count on good schools to prepare the thousands of employees they will need.

There are more than 60, 000 students in the Mobile County Public School System. Their futures shape our future as well, and never more so than today.

|

Educators of Note

Across the county, public schools bear the names of other exceptional community leaders and teachers.

Augusta Evans (1835 – 1909) Mobile’s famous novelist, right, was recognized for her literary achievements and, in the 1952 – 1953 academic year, the board named a grade school for her. It later became a facility for educationally challenged children. The school will soon be moving from Florida Street to a new building in West Mobile.

Erwin Craighead (1852 – 1932) was a historian and longtime editor of the Mobile Register. He was a strong advocate for the local public school system, and Craighead Elementary on South Ann Street is named in his honor. It opened in 1943 in the midst of Mobile’s war-time years.

Peter Joseph Hamilton (1859 – 1927) was an attorney and noted historian whose book, “Colonial Mobile, ” has remained in print since it first appeared in 1897. The elementary school named for him is now part of the Chickasaw School System.

William Henry Brazier (1870 – 1941) began his career at Broad Street Academy in 1891 and served as principal of the Augusta Street School from 1908 until his death. For his long and distinguished service, a new school built in Trinity Gardens was named for him in 1964.

Mary B. Austin (1885 – 1943) served for more than 20 years as principal of the Spring Hill School. In 1943, parents of students petitioned to have the named changed to honor Austin’s long, devoted service. The school is located on Provident Lane in Spring Hill and celebrated its centennial in 2010.

Alma Bryant (1874 – 1986) began her career teaching at the Dauphin Island School, which was a long boat ride from her Bayou la Batre home. She survived the catastrophic 1906 hurricane, chronicled in the book “It’s Time to Leave, ” and went on to be one of her community’s leading educators. In 1918, she transferred to Alba School, and from 1919 until 1955, she taught and served as principal there. Irvington’s Bryant High is named in her honor. Their mascot: the Hurricanes.

Sidney Phillips Sr. (1894 – 1950) served in the army in World War I in the Battle of the Argonne Forrest, taught at Murphy High School, became principal there in 1944 and eventually served as assistant superintendent of MCPSS. His son, Sidney Phillips Jr., is famous for his World War II combat experience in the Pacific. Sidney Phillips Magnet School is named for the elder.

Ariel Williams Holloway (1905 – 1973) was a noted poet, author and musician involved in the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s and ’30s. She came home to teach music in Mobile County public schools, both black and white, from 1939 until her death. Holloway Elementary on Stanton Road is named after her.

Anna F. Booth (d. 1992) was a popular teacher in Irvington for 17 years and assistant principal of Alba High School and principal of Alba Elementary for years after. In 2005, in response to letters from former students, the board named a new elementary school in her honor.

text by Michael Thomason