Pineda Island occupies the eastern end of Battleship Parkway, Blakeley River to its east and Apalachee River on the west. On the south side of the Causeway, travelers stop at Meaher State Park to camp, fish off the pier or picnic. But north of the road, the island is quiet and there’s really no reason to stop. No reason, that is, unless you want an up-close look at the modern-day ruins of the Pineda Island Resort – its soaring, mid-century modern concrete columns giving passers-by a glimpse into the past and the vision of a futuristic community on Mobile Bay.

The story of Pineda Island is a complicated one characterized by hope, tenacity and mystery. It’s named for Alonso Álvarez de Piñeda, a Spanish explorer who, in 1519, led expeditions to map much of the Gulf Coast from Texas to the Florida Panhandle, including Dauphin Island, Mobile Bay and Pineda Island, locally pronounced “Pih-NEE-dah” not “Peen-YAY-dah.” He is said to have been the first European explorer to see the Gulf Coast and is also credited with discovering the Mississippi River.

But our story starts with a man named G.C. “Red” Wilkinson, a developer and businessman who came to Mobile from New York. By all accounts, Wilkinson was a wheeler and a dealer, noted for, among other things, selling the most Packards in the nation from his Mobile dealership in 1962, developing the area of Spring Hill around the Mobile Country Club, starting the first major insurance company in the area and envisioning a thriving, futuristic middle class community by the Blakeley River. Situated between Mobile Bay and the Mobile River Delta and just minutes from downtown Mobile and Spanish Fort, Pineda Island seemed like the perfect place for hotels, a swim club, marinas, casinos, homes, shops and restaurants. There was even talk of an air strip and a veterans’ hospital.

With that intention, he acquired the Pineda Island property around 1956. But by spring 1958, Wilkinson decided to sell the 875-acre property to The Eastern Properties Company out of Florida for $1.5 million – nearly $16 million in today’s money. But he still maintained some property on the island and conducted his business from there in a, shall we say, leisurely fashion, as the editor of The Mobile Journal (published from 1939-1964) noted in 1959:

“Red has established his main office in the showcase cottage he built on Pinedas [sic] Island. Here in a vacation like [sic] setting, with Swimming Pool, Small Boats, Boat Dock and Launching pier, he conducts his affairs in Bathing Suit and Terry Robe at poolside. If the strain of the day’s efforts get [sic] him down, he can be out in Mobile Bay within minutes, or can take off up the Tensas [sic] River and relax with the fish and the birds.”

Ultimately, even this life of leisure couldn’t keep Wilkinson on the island, and he moved to Florida where he continued to successfully develop properties around Fort Lauderdale.

However, during the two years that Wilkinson did own the island, things were happening. Plans were announced for an 80-room Howard Johnson’s and a multi-million dollar Holiday Inn, one of the first in Alabama. And, in June 1958, The Baldwin Times featured a groundbreaking ceremony with a picture of Fairhope Mayor Ed Overton, Mobile Mayor Joe Langan, Kemmons Wilson, founder of Holiday Inn and D.V. Williams, president of the Bayside Motel Corporation. Rebecca Nelson is Williams’ granddaughter, and their company, Bayside Properties Corporation, still owns and manages properties on the island. “When Pineda Island was developed, my grandfather bought his home there. Several homes were built in there. Holiday Inn came in. The island was built, sand was dredged in, the canals were put in,” Nelson recalls. “I think that the property of the original development extended well into the other side of the canal, which is now state property. But the development was not completed, meaning a dozen homes or maybe less were built on the island. The development company pulled out and moved to Florida.”

Then she adds with a hearty laugh the statement that best sums up researching Pineda Island, “Let me caution you. These are some recollections from long ago. Okay? From people who are not around anymore to tell the tale.”

In later years, even though he was never one of the developers of Pineda Island, D.V. Williams had opportunities to buy additional rental homes and lots, ultimately traveling to Florida to obtain the portion still owned by Wilkinson’s development company. “I don’t know, and I’ll never know this,” says Nelson. “I’m not sure if D.V. endeavored to ever have that pool structure property, but whether he wanted it or not, it was part of the deal because those folks wanted out of Spanish Fort.”

“He tried to sell the pool property two other times before selling it to Mark,” Nelson continues. Mark is Jon Mark Meshejian, who, according to the Baldwin County property tax records, is the current owner of the property where the ruins of the Pineda Island resort now stand. Mashejian could not be reached for comment and is, by all accounts, an elusive character, but he has certainly added to the mystique of the pool structure by parking a “Back To the Future”-era DeLorean on the property.

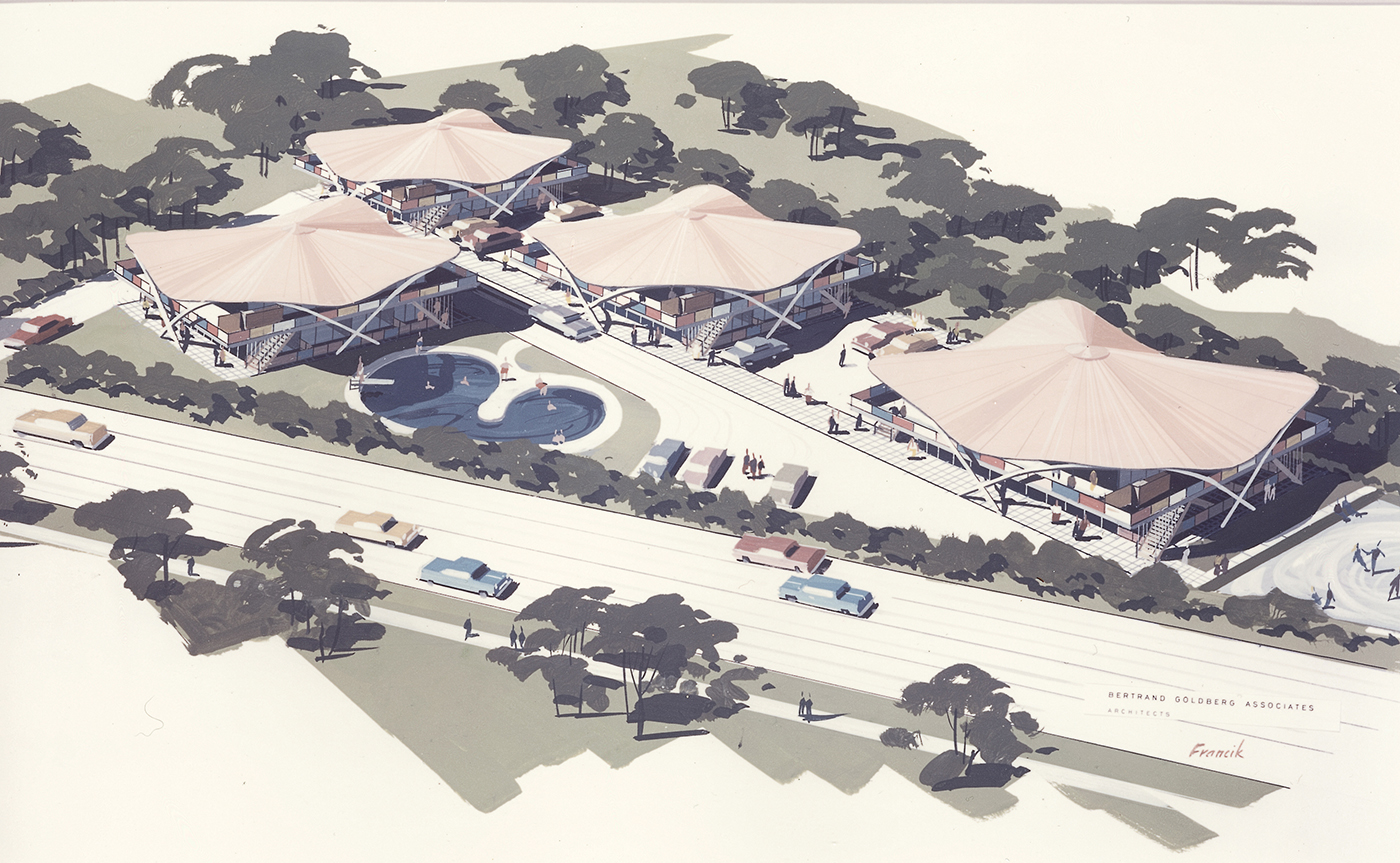

So, like Marty McFly, let’s travel back to the late 50s and pick up our story there. It was during this time that Wilkinson’s original vision began to take shape. As Nelson recounted, work was started, canals were dredged, hotels were built and homes were constructed. It was going to be fantastic. World-renowned Chicago architect Bertrand Goldberg was even hired to design the swim and dive club, the hub around which the Pineda Island resort community would revolve.

Goldberg was a Harvard-educated architect and a student of the German Bauhaus school of design. Known for his experimental designs, he had a lifelong passion for housing and urban development and would later go on to design one of the most iconic features of the Chicago skyline – Marina City, also known as the Corn Cob Towers – which was the tallest residential building in the world when it was completed in 1968. It was designed to be a city within a city, where residents need not leave the building to find anything they wanted – schools, shopping, entertainment. That was sort of the original idea for Pineda Island.

The Pineda Island swim club was to be a showstopper, and glimmers of what it could have been can be seen in a rendering housed now at the Art Institute of Chicago. Blue skies are separated from even bluer pool water by a space-age-style shade structure. There are palm trees and colored flags and bathers gathered in the shade. Views of the bay and the river can be enjoyed from all angles, and one can almost feel cool bay breezes blowing through the open design. It looks like a place the Jetson family might have happily vacationed.

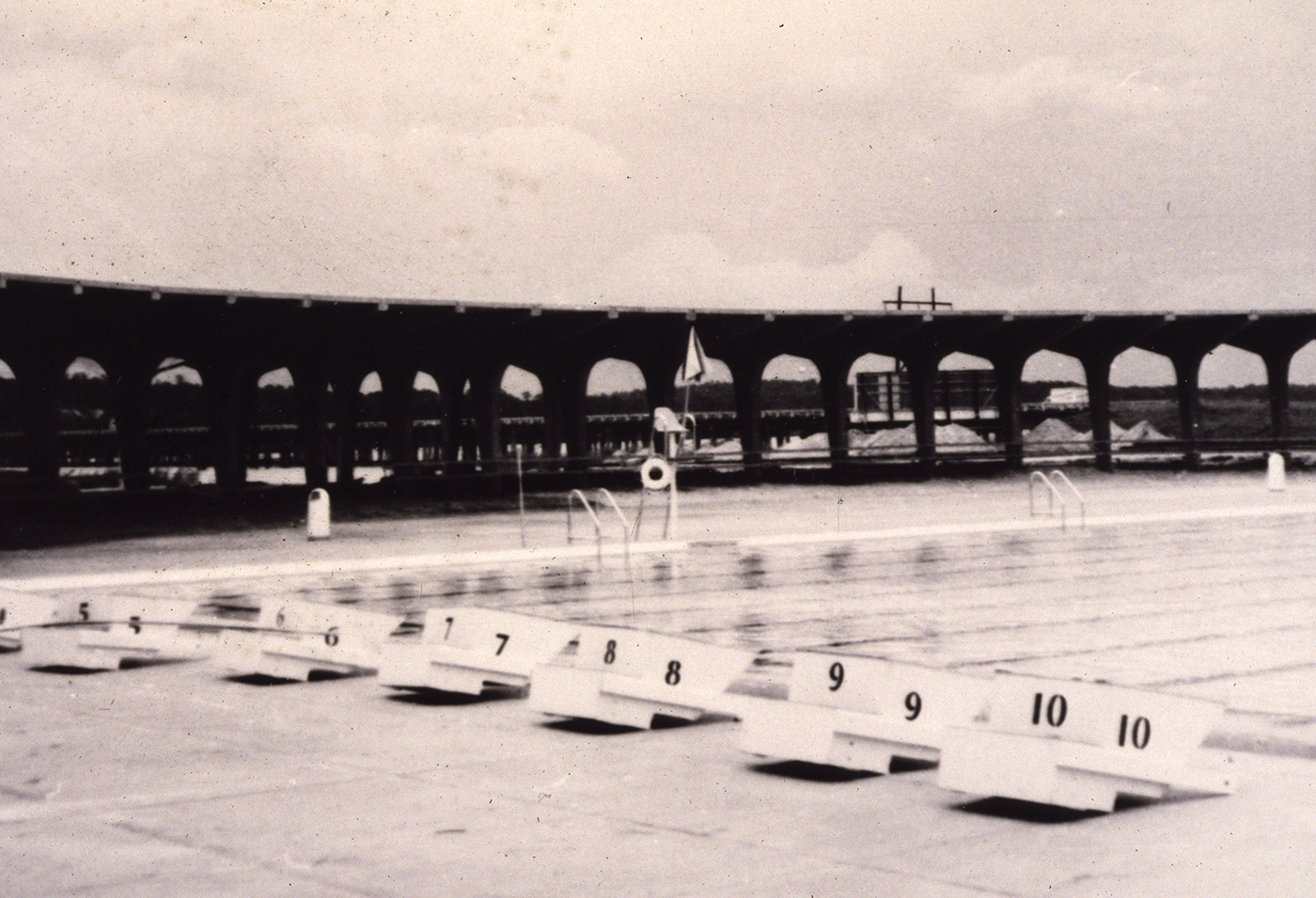

Even though this part of the development was never fully finished, it was near enough to completion to open around Memorial Day weekend in 1958. The Fairhope Courier reported that the opening weekend was enhanced by “the thrilling performance of a crack water ski team from the Eastern Shore.” David Reynolds, whose company, Lifestyle Granite and Cabinetry, is still located on Pineda Island, remembers paying a quarter to swim there when he was a boy of about 12. “Me and my brother used to go and swim in the Olympic pool [and dive] off the high dive. I’m not sure about the height of that board, but the depth of the pool was 16 feet. Wow. And if you went real deep, it would really put a lot of pressure on your ears.”

“It was really interesting, but I wasn’t even thinking about the structure. I was thinking about swimming,” he continues. “We never got in the Olympic pool, the racing pool. We just used the big one, the deep one.”

That’s right, there were not one, but two pools on Pineda Island – a racing pool and a diving pool – and remnants of them can be seen in aerial photos. The largest of the pools was said to have been the only Olympic-sized pool south of Nashville, and in August 1960, it hosted its first, and only, swim and dive meet. Julie Bagwell was there to compete. (In the spirit of full disclosure, Mrs. Bagwell is the mother of Mobile Bay Magazine editor, Maggie Bagwell Lacey.) “I swam for the Mobile Country Club, and I have a patch from it,” she recalls. “The patch says, ‘The Pineda Invitational, 1960.’”

“We were used to swimming in 25-yard pools, double laps, but I think [the Pineda Island pool] was about 50 yards long so it was exciting,” she says. “I remember that it wasn’t landscaped and that it wasn’t finished. We were used to going to pools where you would have a place on the deck that your team would sit with their coolers and their stuff. But I remember it was kind of hard to find a place to be, whether that is because it was too big — it was such a big event — or because they didn’t have the areas around it finished. But the meet was coming, and then it probably did not get any better than that.”

A couple of years after that historic swim meet, the development of Pineda Island stalled and eventually fizzled out. The pools were closed. Hurricanes took their toll on the hotels. Work ground to a halt. But no one seems to know — or be willing to tell — exactly what happened. What caused it to fail so spectacularly? And now, more than 60 years later, all the players have gone on to their great reward. Some say it was state and local bureaucracy that held the whole thing up. Some say the

developers defaulted on the mortgage. One person, who asked not to be named, characterized the whole thing as a “scam” where people “lost [their] shirt.” Ultimately, we’ll probably never know what really happened.

But even so, our story doesn’t end there. While the dream community of the future might not have come to fruition just like Red Wilkinson envisioned, Pineda Island is still home to dozens of residents who wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. Eighty-eight year old Juanita Wiggins has lived in one of the original houses with her husband Charles since 1986. It’s situated directly across the street from the now fenced off remains of the swim club. But even before that, Wiggins worked on the island. She and her husband had a business there. She was secretary and bookkeeper for the manager of the Holiday Inn, and she was also D.V. Williams’ secretary. If something has happened on Pineda Island, Mrs. Wiggins knows about it.

“At the beginning, there were only two houses on this island for residents, and that was the two on the river owned by Mr. Williams. Well, it was built by Red Wilkinson, who developed the whole island, but the first home was on Blakeley River when you go down Caribbean [Boulevard],” she says. “And next to that was the Holiday House. That Holiday House and that residence was the office for Red when he was developing the pool area. And Mr. Hollo, who was the manager at the Holiday Inn at that time, lived in the duplex.”

It’s hard not to wonder how a successful residential development on the island would have changed Battleship Parkway. “I think that it would have been more attractive around the nation, actually, because we get a lot of people coming. You’ll see them up and down the Causeway taking pictures and everything, and it’s been that way for years,” Wiggins says. “And I think that hotels would have flourished. They’ve had three different ones on the Causeway, and they had one up at the top of the hill also. But who could say? Red was good at building up areas. He bought them for little or nothing, and then he would build them up and make them very successful. And that was around the country. Wasn’t just here.”

“It was the size of the pool for one thing. Nothing else was like that. It was just the excitement of something that was so cutting edge,” says Bagwell. “Then it was just suspended. It always looks really sad to me. It’s a disappointment just to know something had potential but didn’t make it for one reason or another.”

But maybe those reasons just don’t matter anymore. After all, life on the island has continued just fine for all these years. And the remnants of the Pineda Island Resort are still just as majestic and beautiful as they were 60 years ago despite their decay – a gray skeleton that rises defiantly into the south Alabama sky as a lasting monument to innovation, progress and the hope for what could have been.