Ciby Herzfeld Kimbrough (1941-2012) was 24 years old and five-months pregnant when she crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965, accompanied by Martin Luther King Jr., Rev. Ralph Abernathy and 600 others. A Mobile native, she took part in boycotts, sit-ins and countless other demonstrations during the civil rights movement. Encouraging her activism was her brother, Dr. William L. Herzfeld, who later became the president of the Alabama Southern Leadership Conference and served as president of the Association of Evangelical Lutheran Churches. Ciby obtained her doctorate at age 63. Together, these two embody the legacy and dream generated by their maternal grandfather, Gaines Frazier. By the time he died at age 99, Frazier had sired 24 children by two wives, operated a farm large enough to support each and every one of them and found success at a time when the odds were stacked against him.

Though little is known about his youth, Frazier was born in Autauga County in 1848, likely into slavery. Prior to the Civil War, many runaway slaves headed south toward Mobile Bay, which may explain his family’s relocation from central Alabama to the Cedar Point Road community. In 1878, Frazier purchased a swath of uncleared land, an unusual occurrence for an African-American at that time. More unusual, however, was the farm’s success, which rapidly grew to include an 18-mule team and a 138-dairy-cow herd. He even laid a road, which is now called Doyle Avenue, from Cedar Point Road to Old Bay Front Road to shorten his trek to town. Part of the road was eventually closed off when the government bought it to build a runway at Brookley Air Force Base.

Most of what is known about this fertile farmer, so to speak, comes from the family history of her grandfather written by Kimbrough. Of the chores on the farm, she wrote, “Before the sun rose each morning, the females would prepare a big breakfast for the family. After breakfast, the men and boys would leave to work in the fields, tend the milk cows and peddle milk and butter. The females spent the rest of the day cooking, cleaning, making clothes, canning, washing, ironing, tending the garden, picking fruit and tending the yard animals. The males hunted raccoons, squirrels, rabbits, deer, quail, duck and wild turkey to feed their large family. They also fished. With as many as twenty-five to thirty family members present for a meal, they needed a lot of food.”

Frazier, with incredible foresight, saw how important an education would be for his children. To ensure this, he donated some of his land and helped build the only school for African-Americans in the area, Race Track Elementary. But Frazier didn’t just give his children an education, he passed down his work ethic, a determination necessary to operate a farm without modern technology. “Horses and wagons were used for the first fifty years of the farm. A pump was the only source of fresh water. There was no indoor plumbing,” Kimbrough wrote. “There was no electricity! Every day was filled with work, work, work!”

Despite the prosperity of Kimbrough, Herzfeld and other descendants, the farm itself is long gone: sold, destroyed, buried. Speaking to its legacy, Kimbrough wrote that “while time stood still on the farm, Mobile grew all around it. Our uncles got old, but the needs on the farm continued to be demanding. One by one they died. There was no one left to do the work because all of the grandchildren had made their lives away from the farm. The last time I saw the farm, it was under demolition. The house, store and barn were all gone. The shade trees had been uprooted. It was painful to see.”

Despite the prosperity of Kimbrough, Herzfeld and other descendants, the farm itself is long gone: sold, destroyed, buried. Speaking to its legacy, Kimbrough wrote that “while time stood still on the farm, Mobile grew all around it. Our uncles got old, but the needs on the farm continued to be demanding. One by one they died. There was no one left to do the work because all of the grandchildren had made their lives away from the farm. The last time I saw the farm, it was under demolition. The house, store and barn were all gone. The shade trees had been uprooted. It was painful to see.”

Gaillard Elementary School now occupies the space of the old Frazier farm, a fitting tribute for a man who valued hard work and education.

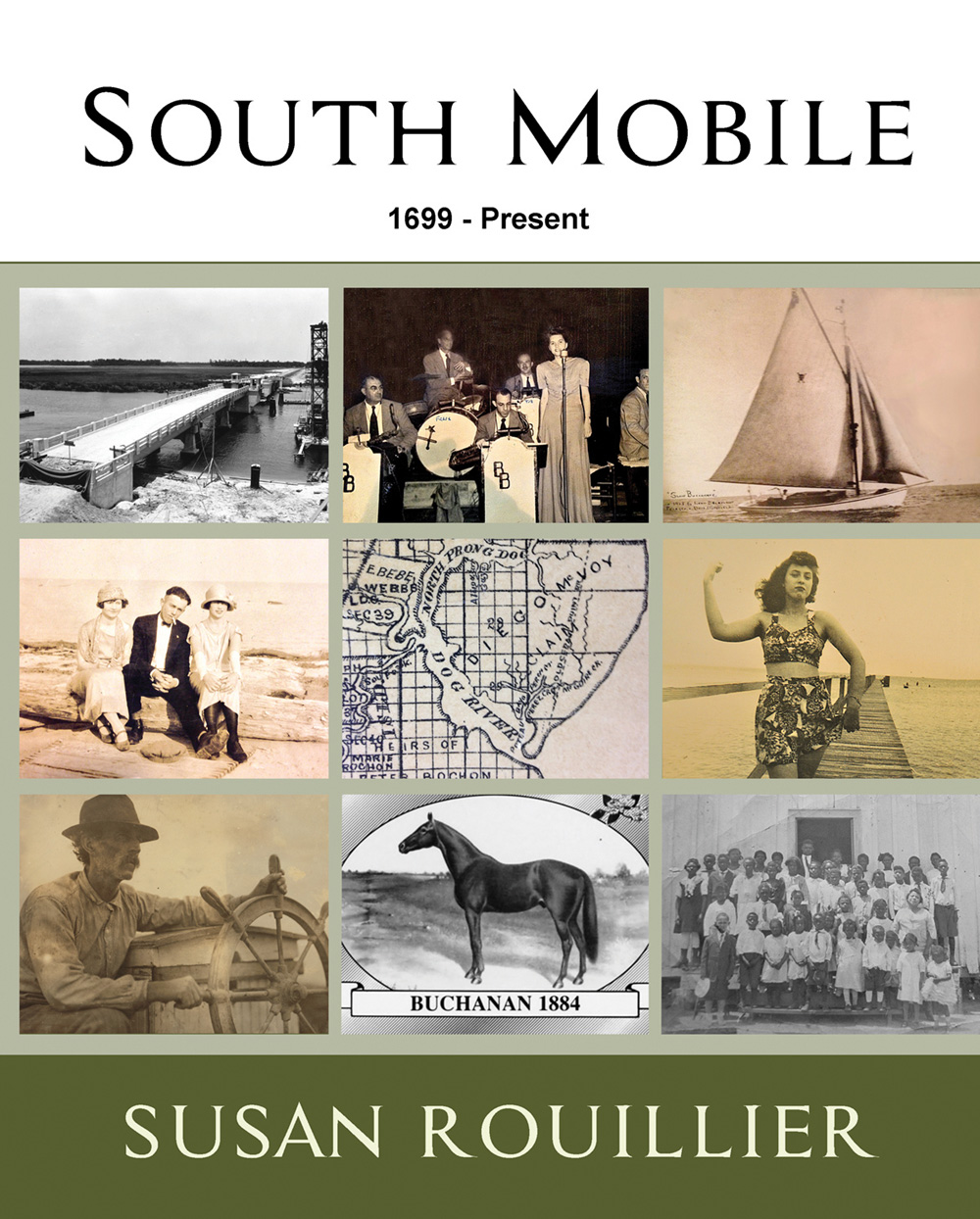

Excerpts borrowed from the book, “South Mobile, 1699 – 2018” by Susan Rouillier, available on Amazon, at the Haunted Book Shop, at GulfQuest Maritime Museum and through the author at [email protected]. Susan is an avid bird photographer and painter who lives on the western shore of Mobile Bay in South Mobile.