Above Wallie Valrie visits the Greenwood home on Monterrey St. in Mobile in 1946. Image courtesy of the Arnetta Sims Collection

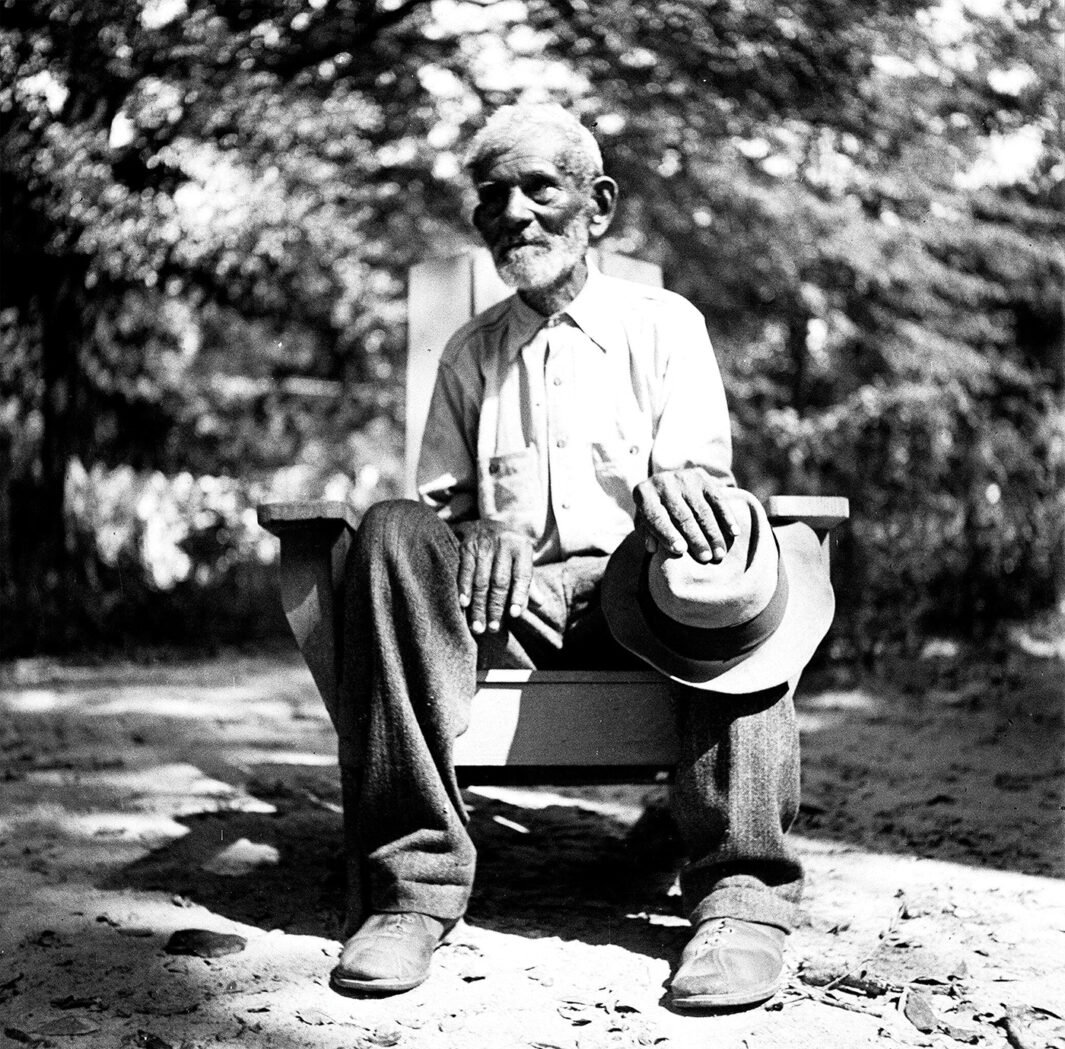

In the Montrose Cemetery, toward the back and on the right, is a live oak, shading a cluster of graves. With the lack of rain, the resurrection fern covering the limbs was brown, waiting for moisture. A tropical storm that would become Helene had just entered the Gulf of Mexico. Despite the week-long drought, the cast iron lily was full, lush and deep green. Beyond the lily and under the sprawling live oak canopy lies the resting place of Wallie Valrie, former slave of Greenwood Plantation, Montrose resident and founder of a Catholic church. Descendants of “Grandpa,” as his kin refer to him, have been tracing his genealogical roots, which run deep and wide, like the live oak he’s resting under.

Arnetta Sims, Wallie’s great-great-granddaughter, was born and raised in Montrose and has worked for the city of Daphne for over 10 years. After graduating from Faulkner State Community College, now Coastal Alabama Community College, in the 1980s, she returned to school and earned her degree in theology from Spring Hill College in 2012. For the last four years, Sims has been sharing Valrie’s up from slavery story.

Thumbing through some of her research at the Daphne Public Library, she says, “Sometimes I ask myself, ‘What am I doing with a degree in theology?’ This is what I’m doing: genealogy,” she said with a laugh. “Writing those papers and doing the research is what the Jesuits taught me.”

Born in 1832, Wallie Valrie was the son of a French slave owner and his Cherokee maiden, who was a slave, according to an article in the Eastern Shore Courier in 1982. He was raised at Greenwood Plantation, which was named for John Alfred Greenwood and his wife, Rosa Serra, who were 46 and 31 when they acquired the 320-acre land grant, recorded at St. Stephens in 1820. A 39-acre parcel was co-owned with Greenwood and Reuben D’Olive.

In an interview with a Mobile Press-Register reporter in 1946, Valrie recalled as a young child playing marbles with John Greenwood, the owner of the plantation. Though he is not named specifically, Valrie was one of 20 slaves on the Greenwood Plantation, according to the 1860 Slave Census. Valrie was a house servant. “He was a messenger between the Greenwood, Hall and D’Olive families,” Sims says as she turns pages from a folder of historic records.

Above Arnetta Sims at the grave of Wallie Valrie in the Montrose Cemetery. Photo by Chad Riley. Above This building is believed to be the Greenwood Plantation smokehouse. Images courtesy of the Arnetta Sims Collection

When the Civil War ended, Valrie remained for many years in the area. A Mobile Daily Times account from 1866 shares news of a naval store in Baldwin County’s forests. A new Greenwood Brothers and Co. turpentine still was having its first run. “The first of the kind…in this state…cost over five thousand dollars.” The Greenwoods party, of 180 “including some thirty ladies,” watching and waiting for the first run. In five hours, the still turned out 170 gallons of turpentine and 16 barrels of virgin rosin.

The success called for a celebration. The article claims that nobody drank the turpentine, although “there were many a brave Confederate soldier who […] would have called it ‘pine top whisky.’” The champagne of the “widow Clicquot” was “hugged around,” with guests enjoying the “sparking sprit!” Though Valrie claimed to have never drank, one of his keys to a long life, he was there for the festivities.

Valrie married Melinda Webster (1855-1945) on December 30, 1871. They would have 11 children. Sims has been in close contact with a person who is also related to a former slave from the Greenwood Plantation.

Marquis Watkins is a descendant of Amey Greenwood Phillips, who was onboard the last slave ship, Clotilda, before she was sent to Greenwood Plantation. “Greenwood was in the middle of Baldwin County. It was a major place between Pensacola and Mobile Bay,” Watkins added.

Above John Greenwood and his wife, Rosa Serra Greenwood, were married in 1831. Greenwood was born in England and brought to Florida in 1806, and Serra was born in Pensacola in 1809.

The location was important prior to Greenwood because it was on the Old Spanish Trail. “Later, there was a stagecoach from Greenwood all the way to Selma,” Sims said. “We’re talking to Greenwood descendants from around the country, but especially in Florida, Mobile, and in Tennessee,” Sims said. Greenwood is identified on the 1872 and 1889 versions of “Boudousquie’s Reference Map.” The early map shows Greenwood near yellow and long leaf pine “virgin forests.” Today, the Greenwood Plantation Cemetery and the Greenwood Springs Branch, a tributary of the Styx River, mark the plantation’s vicinity.

Though there is no known photograph of the plantation home, which burned down, Sims is hopeful that one will surface as they reach more Greenwoods. She recently received a photograph of what is believed to be the smokehouse at Greenwood. In 1900, Valrie purchased land in Montrose (just south of today’s Daphmont subdivision) where he continued to farm on a 30-acre tract of land. “He walked to Daphne every day,” Sims said. His first stop was to have coffee with his daughter who lived on Thomas Ave. Valrie also visited the Baldwin County Training School where he talked to the students about his life experiences which included his 31 years in slavery to freedom.

We also know he visited another Montrose neighbor, Henry J. Stuart at his round house in Tolstoy Park. Recently discovered journals by Stuart record visits by Valrie in the late 1920s.

Valrie’s spiritual legacy continues. He was actively involved and credited with establishing the Shrine of the Holy Cross Catholic Church in Daphne.

In the 1946 newspaper article, Valrie was “fighting mad” at the founders of Loxley for letting Greenwood fall off the map. John Loxley, Loxley’s namesake, and the Mahler family were founders of Loxley and purchased property from the Greenwood family, according to property searches completed by Sims. Two hundred years later, the area known as Greenwood Plantation remains active farmland, including what is now part of Flowerwood Nurseries and other farmland east of 59 and south of Interstate 10. John Greenwood’s grandson, “W. H. Greenwood, who lived in Mobile, on Monterrey Street, sent for Valrie,” Sims quoted, and smiled, “They hired a professional photographer to capture the memories.”

When asked late in his life, Valrie attributed his long life to his love of God, the rejection of the devil and never crossing his legs. Although he lived to be 116 years of age, Valrie passed away just a few months before the church was dedicated in 1948. He and his wife Melinda and other Valries are buried in the Montrose Cemetery. Valrie was survived by five sons and a daughter, twenty-nine grandchildren, fifty-four great-grandchildren and 28 great-great-grandchildren. Greenwoods and Valrie descendants continue to meet in person and virtually.

It was at the Greenwood Plantation Cemetery that Sims deepened her connection to Valrie. A handful of Greenwood and Valrie descendants have been to the former plantation site on private property. When she visited the cemetery, “A peace I never had before came over me,” Sims recalled, and she scooped up some handfuls of dirt and poured them into a glass jar. “It was just like my momma described it years ago.” Sims said, pausing to reflect on the cemetery visit, “we have a history at Greenwood.” mb

Alan Samry is the author of two books about Fairhope as well as “Stump the Librarian,” a memoir and history of leg amputees. He is a librarian at Coastal Alabama Community College.