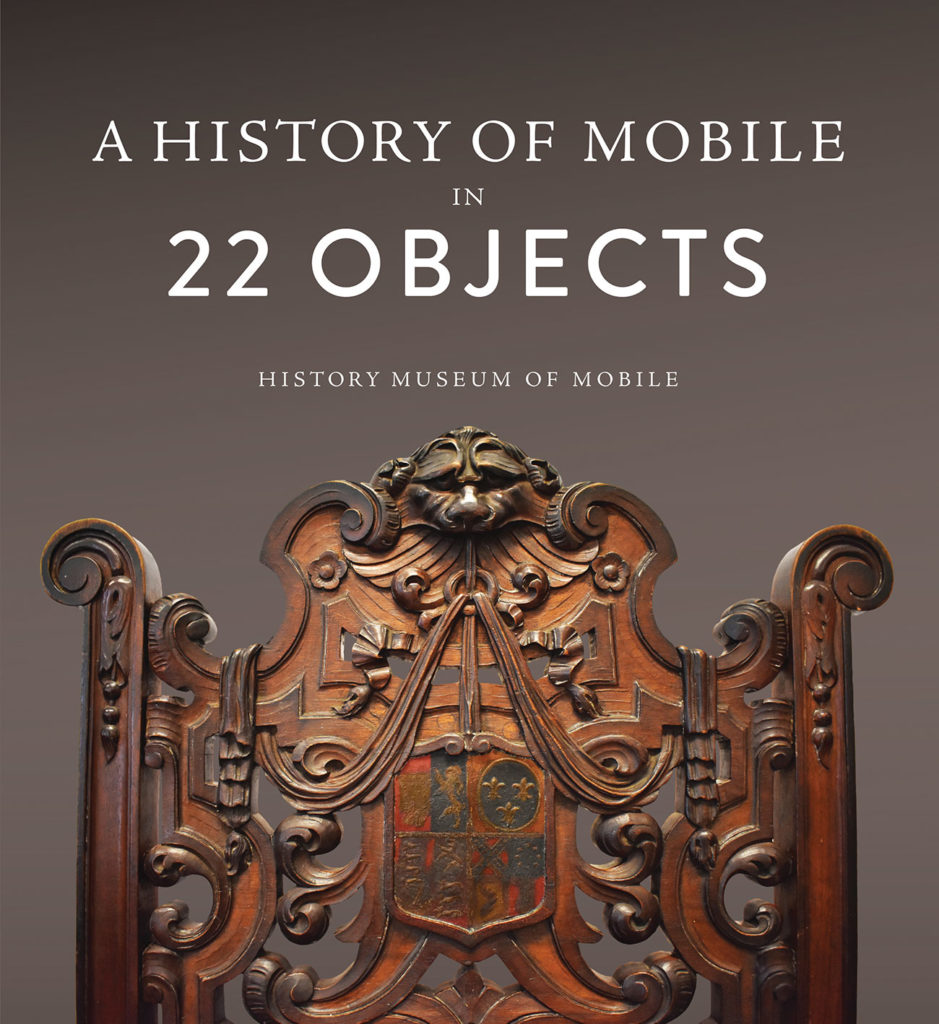

Museums exist to tell histories through objects. In a new publication and corresponding exhibition “A History of Mobile in 22 Objects” (October 30, 2020 – December 31, 2021), the History Museum of Mobile has endeavored to tell a very big history through a decidedly small number of objects. Twenty-two unexpected and compelling artifacts from the museum’s collection weave together over 300 years of Mobile history, from the pre-Colonial era to the 21st-century port. Together, they are an accessible, object-based guide to Mobile history.

What follows is the first installation in a series of essays, taken from the catalogue “A History of Mobile in 22 Objects,” that will highlight 12 of the 22 objects. With essays by the region’s leading historians, professors and museum curators, you are sure to discover stories both new and familiar.

Within the History Museum of Mobile’s collection of over 117,000 objects, there are, of course, so many stories yet untold — challenging things, beautiful things, important things that make up the many histories of Mobile. It would have been a far easier task to choose 50 or 150 objects that tell the region’s long history! For this exhibition, the selection was sometimes limited by the contents of the museum’s collection; in other cases, objects were chosen in order to tell diverse or unexpected stories. There was an effort to choose objects that tell different types of stories, too: those of leaders and everyday workers, of mass culture and politics and economic development. We offer visitors the opportunity to tell us, “What are we missing?” — knowing that this always-important question acknowledges both the limits of our endeavor and how curatorial choices shape the historical narrative.

What you’ll find within this exhibition and catalogue is a history of Mobile — not the definitive history — and not the only story that could be told. By dramatically limiting the number of objects, we bring into relief what historians and curators do every day, that is, to select particular groupings of objects or facts and then string them together into a coherent narrative. Constraining so severely the number of objects in this exhibition serves only to render more obvious this process of selecting, choosing and creating narratives in which historians are always engaged. Different objects, different choices, would have told a different story.

Each and every object in the History Museum of Mobile helps us understand a bit of who, why and how we are. Fortunately, this exhibition does not have to be the final answer of Mobile’s story. The History Museum, like all museums, will continue collecting, preserving and interpreting the artifacts that hold our shared history. Our story is not yet done, our history continues to be made and our successors will have many more tales to tell.

Creole Mobile

by Christopher A. Nordmann

Creoles of color were an integral part of the city and county of Mobile, especially through their participation in Creole civil organizations. The most famous example of such an organization is the Creole Fire Company No. 1, Mobile’s first volunteer fire company founded in 1819 and not disbanded until 1970. The Company did much more than fight fires, though, and was at the very heart of a vibrant social experience for over a century. Donated to the History Museum of Mobile by a descendant of a member of the Creole Fire Company, this silver-plated coffee urn brings to life the social aspects of the Company’s firehouse and the community that developed around it.

What it meant to be “Creole” changed over time and across communities. In Mobile, the word originally referred to descendants of the first French or Spanish settlers, and some Creole families in Mobile trace their ancestry back to the 1700s. (Even into the 1920s, many Creole elders spoke a distinctly Mobilian dialect of Creole French.) More commonly, though, a reference is to “Creoles of color,” typically the children and descendants of a white French or Spanish father and a black or Creole woman, either enslaved or free. Given the harsh social distinctions in a slave society, Creoles of color were sometimes considered second-class citizens, although many were wealthy, had political ties, and played a major role in shaping early Mobile history. Their faith, family, and community were important aspects of their daily lives.

The Creole Fire Company No. 1 was at the center of this community’s commitment to civil involvement and service. For some families, serving in the company was a family tradition. A member of the Trenier family, for example, participated in the Company throughout most of its history. But membership was about more than fighting fires. Minutes from an 1867 meeting of the Creole Fire Company contain “Tributes of Respect” (remembrances of recently deceased members) and notices to assist sick members. Upon the death of a Creole fireman, the organization adopted a resolution offering their sympathies to the family of the deceased fireman, and members wore a badge of mourning. For many decades, the social event of the year for the Creole Fire Company was the annual April torchlight parade, followed by a dance. Local newspapers published the parade route — during the antebellum years, it started at the engine house on Joachim Street — and Mobilians eagerly lined the streets to watch the marching Creole Band entertain onlookers. Local leaders like the mayor, president of the board of aldermen, and editors of local newspapers would receive invitations to the parade and ball. The Company took pride in public praise from the press. The larger Mobile community warmly supported their efforts, and the Creole citizens responded by making their parade a memorable evening for themselves and the rest of the city.

Creoles of color experienced varying degrees of legal rights and autonomy throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The Louisiana Purchase Treaty of 1803 and the Adams-Onis Treat of 1819 (in which Spain renounced claims to West Florida and ceded East Florida to the United States) guaranteed political, property, and legal rights to free residents of Louisiana and their descendants. However, by the turn of the century, state and local regulations intended to disenfranchise former slaves (like the Alabama state constitution of 1901) also affected the Creole population. While they maintained an active community presence through the Creole Fire Station, the Creole Social Club, the Catholic Church, and church schools, systematic segregation impeded their participation in the political and public sphere.

From the creation of the Mobile Fire Department in 1888 and over the course of the twentieth century, members of Creole No. 1 became increasingly assimilated into the municipal fire department. This union was completed in 1970, when the Mobile Fire Department was officially integrated. By 1971, all remaining members of the Creole Fire Company had been dispersed amongst other MFD units.

As the firemen and their families gathered around this coffee urn at the Creole Fire Station in 1913, they may have been discussing how they could improve their community by helping other Creoles in need. Today, identifying oneself as a Creole is a matter of family pride and community heritage — and a celebrated 300-year-old tradition in Mobile.

Christopher A. Nordmann, Ph.D., is a professional genealogist (specializing in tracing the lives of African Americans) and an award-winning author whose publications deal with African American history and genealogy.

“A History of Mobile in 22 Objects”

Released in conjunction with the History Museum of Mobile exhibit, this photo-heavy compendium delves into the city’s history through the analysis of 22 artifacts by Mobile’s leading researchers.

Click here to purchase your copy.