The cars are silent, and that makes Chris Carter antsy. From the racetrack’s broadcast booth, his voice begins to rise and crack over the din of the grandstands as he looks down at 21 cars aligned in two neat rows. The driver of the No. 28 car is strapped into his seat with an anaconda-like grip, staring in the only direction his range of motion will allow, straight ahead. His mother, a picture of serenity from the ankle up, taps her right foot as she watches from a stand in the pits. Finally, Carter can hardly stand it.

“Are you ready? It’s time, y’all! Now, I want to hear everybody say it with me. Here we go, the most famous words in racing: Gentlemen, start … your … engines!”

And with those four words, the night sky erupts. The mazes of pipes and tubes riding shotgun beside each driver fire forth like the Hades Philharmonic.

Earlier in the day, while the summer sun was drying out the track and all the tires still had tread, many people had their hopes hitched to this moment. The workers at the track’s entrance all smiled. They politely yelled directions to me, and I felt my pockets to make sure I remembered earplugs. I prayed my Wrangler jeans, coupled with a passable usage of the word “ain’t, ” would make folks more likely to befriend a wanderer on pit row. I drove over the steep lip of the bowl, across the track and into the grass infield, where I parked among raised pickups and NASCAR stickers. Friends, I soon realized, would be here for the making.

Qualifiers

By the time I meet Steve, a former drag racer from Chicago, it’s occurred to me that most people here know more about crankshafts than I know about well near anything. Steve drove to Irvington from Navarre, Fla., and, like me, is wandering the pits alone. In his early 50s, he appreciates my need for a race night tutorial.

“You’ve got four classes, ” he begins in a mustard-thick Chicago accent. “The bombers go first.” He stops to let a car peel through our corner of the track; conversations at the Speedway tend to occur in 15-second installments. “So the bombers go first, after everyone has qualified for their start position. That’s followed by the sportsmen series, and then the modifieds run. They’ve actually added trucks to that now because they didn’t have enough for their own race. And finally we’ll have the super late models.”

We walk a lap around the inside of the oval, weaving to avoid the paths of cars and crewmembers. As Steve is explaining how the pits have become a family environment — how sons, brothers-in-law, moms and sisters have become more involved in recent years, how they even stopped selling beer there — I watch a small girl in grungy pink jeans stroll next to a car and stop behind a man squatting at its front tire. She nudges him and smiles while she talks, the way a daddy’s girl will do. “You’re gonna get your hands dirty, ” I hear her father warn. “Daddy, I don’t care, ” she replies, and the man scoots over so she can help with the lug nuts.

As the time trials wind down, I count 68 racing fans scattered throughout the grandstands. Steve and I return to the inside of turn four, where a middle-aged, petite woman rises to her tiptoes and whoops wildly each time a car passes.

The Bombers

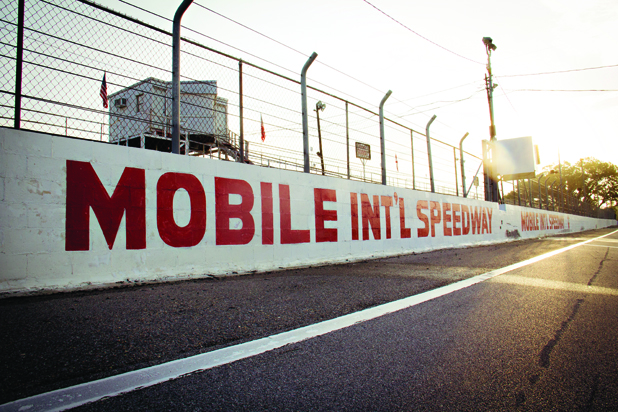

Mobile International Speedway boasts one regular driver from Canada, so its name is correct technically. More aptly titled, however, are the cars in the bomber class. Most of the tank-like bodies look as though someone used mallets to play a drum solo on their metal. The racing number for one car is stuck on in fluorescent orange duct tape. A few of the bomber engines vroom the way a racecar should. Others sound more like a fireworks stand burning to the ground.

The day’s first race starts without much fanfare, but a few laps in, one car suddenly smashes its front-right corner into the wall. “Steering done broke, ” the petite woman leans over and says to me. The car bounces downward before heading straight back into the cement barrier. “Yup. Might’ve lost his steering wheel.” The crowd rejoices in the smoke and the crunch. With the caution flag waving, the pace car zooms onto the track to escort the drivers until the car can be removed.

Shortly after the incident, the woman turns and says something else to me, inaudible over the thundering of the race. I laugh and nod, a move I picked up from watching every old man I’ve ever known. She walks over to the shiny, steel-colored Camaro convertible sitting 20 yards away and yells into the driver’s ear. He pulls up one side of his headset and gives a businesslike nod. “Alright, ” she says, coming back. “Go get in.”

As soon as I sit down, before I can even think about a seatbelt, the crowd cheers again and the yellow caution flag shoots out from the flag stand. My laconic driver punches it from zero to 90, and we swerve in front of the oncoming racers like a couple of snowbirds barging onto the interstate. The lead racer slows down only once the sweat beading on his brow is visible in my rearview mirror.

After the race, I walk by Derek “Kane” Long, local “eye in the sky” traffic reporter and driver of the No. 5 bomber. His car collected a few new dents, including some from a fracas that sent it careening over the top of the backstretch en route to an eighth place finish. Long’s grinning face is dripping with sweat as he pulls off his gloves. “Boy, ” he says. “That was fun, wasn’t it?”

Sportsman Series

Fun, Tommy Praytor tells me, is the only dividend most of these drivers expect from their sizable investments in auto racing. Tommy, whose son Thomas drives the No. 28 Praytor Realty car, hosts racing shows on radio and television, and handles a portion of the Speedway’s promotional work. (He spins a tale about coaxing Warner Brothers filmmakers to Mobile International Speedway, where they eventually decided to film the opening scene for the fourth movie in the Final Destination franchise.)

“At the end of the day, everyone’s out here because they love it, ” he says. “There’s 43 guys that get to race on Sundays (for NASCAR). There’s 100, 000, maybe 200, 000, guys around the country that want to be in that 43.”

As head of the Max Force Racing Team, the 53-year-old Praytor scowls a lot, but he smiles a lot, too. When Tommy began a late-blooming racing career 20 years ago, Thomas was too young to enter the pits, so father would sneak son in to be his spotter. Now, it’s Tommy who watches from spotters’ row, keeping his binoculars circling Thomas’ car as he radios instructions and the positions of nearby drivers. “Dale’s on your bumper, ” the elder Praytor will say. And during a pass: “Inside. Inside. Inside. Still there. You’re clear.”

Thomas, better known as “Moose” around the Gulf Coast circuit, began racing at age 9, before he even had a learner’s permit. He continued competing through his years playing high school football at St. Paul’s, where as the team’s center he snapped the ball to current University of Alabama quarterback A.J. McCarron. Now 22, tall and sturdy, he acts somewhat puzzled when I ask why he chose the number 28 for his car, and perhaps I should have known. “Well, that’s the number he used, ” he says, with a nod toward his father. The elder Praytor picked the number because Thomas and his twin sister, Hayley, were born on February 28.

The Modifieds

Tommy steers a golf cart around the pits, stopping here and there to shake a few hands as the grandstands continue to fill. Before the second-biggest race of the night, he continues the lesson Steve started earlier. “Family’s everything here, ” Tommy explains. “This is our hunting and fishing. But instead of leaving my wife and my daughter at home for the weekend while we go to the hunting camp, they can come to the racetrack and be involved.”

The shift toward a family environment has affected other aspects of race night, including how the drivers treat each other. Tommy tells me about a recent time when a friend accidentally bumped Moose out of a race. When the offender later tried to make amends, the younger Praytor’s ears were clogged shut with rage.

Tommy told him, “Son, this stuff happens every week. Next week it could be us going down to him to apologize.” He pauses. “To me, it gets back to the family deal. There are so many lessons being learned here that have nothing to do with car racing.”

We cruise back to the Praytor Realty trailer, something like a shiny garage on wheels, where the team is preparing. Despite the common perception of racing as a “redneck” hobby — a notion stemming back to the sport’s moonshine-soaked, Appalachian roots — being in the pit area doesn’t exactly feel like hanging out at your local honky tonk. Teams often spend six figures on trailers replete with glass doors, mechanical awnings and air conditioning. Many pay their team members by the hour.

The Max Force Racing Team, a yellow-clad amalgamation of family members, childhood friends and longtime confidants, volunteer their time and talents to help Thomas. As race time approaches, most of them seem more anxious than anyone named Praytor.

Super Late Models

The super late model run is the night’s feature race, a veritable best-in-show competition held over 100 laps. In the Speedway’s heyday, NASCAR’s infamous Alabama Gang — some boys named Allison and Bonnett and their buddies — whorled stock cars around this steep, half-mile bowl with gleeful abandon. This evening, the brightest stars of Irvington include an up-and-coming 14-year-old Georgia native named Kyle Benjamin, who has already won a race tonight; a young woman from Pensacola named Johanna Long, who inevitably attracts more Danica Patrick comparisons with each trip to the winner’s circle; and a collection of young, local favorites who have grown up underneath steering wheels.

After getting the final race off to its rock-show start, Carter continues to highlight the action over the track’s PA system. In the first few laps, a car spins out of control in turn four and misses Thomas’ car by inches before knocking another off the track. “Oh, Lord!” Carter cries. “I need a B.C. (Powder) right now!” The same course of action unfolds as before: smoke, cheers, caution flag, pace car. Finally, a green flag unfurls once order is restored.

Things never quite come together for Thomas, and halfway through lap 87, the mood suddenly shifts. Twenty laps earlier, Tommy had directed his son to make a charge, his voice booming over the team’s headset frequency. “Now or never, ” he had said. But now, as Moose is struggling to keep his car low with every turn, Tommy lets up. Hope of a rendezvous with the checkered flag has run dry. “I see something is wrong with your car, ” he says, carefully enunciating the words. “Thirteen laps to go. Let’s finish the race.”

“Yes, sir, ” Thomas replies, the same way he has all night. A few laps later, his voice returns to my headphones. “Good race, everybody. I appreciate y’all doing what you could. I wish we could’ve had a better car, and I could’ve done a little better, but we made it 100 laps.”

Moose climbs out of his car just as a young man from Senoia, Ga., by the name of Bubba Pollard, finishes his victory burnout at the finish line. Thomas hugs his mother, Julia, and soon begins helping his crew in the cleanup process.

Carter’s voice, more subdued now, once again echoes across the track. “Super late model winners’ checks can be picked up at the pit concession stand.” No one on the Praytor team flinches. None react at all. Thomas takes a sip of Gatorade and continues packing up. “We’ve got work to do, ” he says eventually. Even out of the driver’s seat, the only direction for him to look is straight ahead.

October 27 • Halloween Demolition Bash

Car-to-car trick-or-treating and costume contests. Races include Island Motor II Bombers, Bob’s Speed Shop Sportsman, motorcycles and demolition derby. mobilespeedway.net

text by Ellis Metz • photos by Ashley Rowe