According to Sian Beilock, a cognitive scientist and president of Barnard College, “It begins early, when girls as young as six stop believing that girls are the smart ones.” As those girls mature, that belief causes them to shy away from careers thought to be reserved for men, and with fewer women in those particular fields, the pattern continues.

“It’s a vicious cycle,” Beilock argues in the Harvard Business Review, “but it can be broken.” While only 7.2 percent of women worked in full-time male-dominated occupations in 2018, women’s job growth is in fact driven by employment in male-dominated fields. According to the New York Times, employment growth for women between 2016 and 2018 was concentrated in sectors that are at least two-thirds male — but there’s still work to be done. As research has shown that women exposed to powerful female role models are more likely to ascribe to the notion that women are suited for leadership positions, MB presents the following ladies as examples of the wonderful results of a cycle broken.

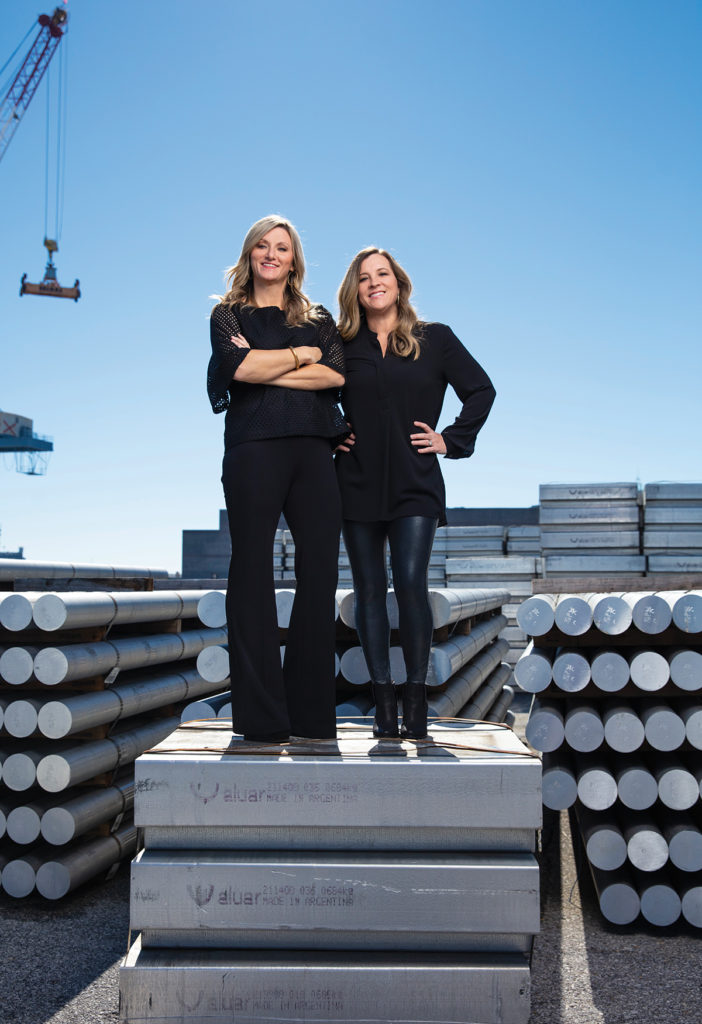

Natalie Barrett and Shannon Ladd

Owners of Streamline Logistics, LLC

For whoever is working operations on a given day, the dispatch calls, texts and emails start around 5:30 in the morning and don’t cease until 8:30 at night. Natalie Barrett and Shannon Ladd, freight brokers and owners of Streamline Logistics, have learned two important lessons: take alternate days working operations, and switch the cell phone to vibrate mode.

“Otherwise, you will hear the tinging sound in your sleep,” Barrett says, estimating that a single day is good for 500 texts and 1,500 emails.

Becoming freight brokers, the middle men (or women) between a shipper who has goods to transport and an authorized motor carrier, was not an obvious choice for the pair. Barrett and Ladd communicate with men all day, every day; females only make up about 8 percent of drivers and 14 percent of managers in the trucking industry. Having known each other since kindergarten, the two women joined forces in 2005 when Ladd, who was working at a stevedoring company in Mobile, approached Barrett with a business proposal. Both unmarried at the time, Barrett and Ladd, now busy mothers, credit a certain youthful fearlessness for the decision.

“At 25, we were on top of the world and just thought, ‘What do we have to lose?’” Barrett says. The duo managed to move $1 million in freight their first year and have continued to grow ever since, transporting commodities such as lumber, fiberglass, copper and aluminum. While people are often surprised to discover the extent to which the two young mothers excel in such a male-dominated industry, Barrett and Ladd say that relationships, not gender, rule the day.

“Sometimes our customers find that the huge freight brokers can’t move certain lanes (trucking routes), and they can’t believe that these two girls from Alabama can,” Ladd says. “Well, it’s because we’ve been doing it for 15 years, and we’ve established relationships using the same carriers.”

For other women interested in the industry, the pair says, take heart. “I would definitely encourage people to take the challenge, the risk, the leap of faith,” Ladd says. “Logistics is such a broad field. There’s so much opportunity but not a whole lot of experience in this industry, so if you do have experience, the opportunities are endless. And just be strong and aggressive, because I don’t think there’s anything a female cannot do in this business.”

Sylvia Browder

Owner of Specialty Home Services, LLC

“I’m the hard-hat-wearing boss lady,” says Sylvia Browder, behind a big smile. “That’s what the guys call me: Boss Lady.”

Browder is the boss lady for nine part-time handymen at Mobile’s Specialty Home Services, the janitorial and home improvement business she created in 2015. What started as a word-of-mouth cleaning service has grown into a successful enterprise, covering the gamut of home repairs. Browder, born in Phoenix, raised in Detroit and most recently relocated from San Diego, is no stranger to small business ownership; she operated a commercial cleaning company in San Diego. Browder is also a business consultant, helping women start or expand their businesses.

According to her, female ownership in the home repair industry is next to zero, a fact that is reiterated every day by the surprised faces of her new customers.

“I get it, and I understand that I’m not in a traditional industry. So it doesn’t bother me that they’re surprised,” she says. “Sometimes I get a chuckle out of it, especially when they assume that it’s my husband’s business.”

Female ownership does come with its challenges. Some handymen, Browder says, don’t last long due to an unwillingness to work for a woman or a disagreement over pay. “So I’ve had to get rid of them,” she says. But most of the time, customers are intrigued by the friendly business owner on their doorstep.

“Whenever I go out and do an estimate, people are pleasantly surprised that I’m the boss and that I came out to the call … they’re surprised that not only am I a woman but a minority. And I know my stuff.” At the end of the day, Browder says, that’s what counts to a customer.

“Success comes to people who do good work,” she says. “Honesty and integrity have to be your ruling qualities.”

Browder’s work as a business consultant also allows her to practice her second passion: helping other women succeed. It’s a mission that’s close to her heart because, without the encouragement of one woman, Browder might not have become a business owner. Before starting her first janitorial company, she approached her friend, Brenda, who already owned a small cleaning service. “I don’t want you to think I’m trying to compete with you, but can you give me some advice?” Browder asked.

Taking her by the hand, Brenda replied, “Sylvia, there’s enough work for everybody.”

“It gives me chills,” Browder says, “because those words are still in my mind. If more women helped other women, just think how bright this world would be.”

Lieutenant Julia Mundy

Commanding Officer, USCGCManowar

At the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) Sector Mobile, near Fort Whiting, Lt. Julia Mundy steps onto the 87-foot cutter Manowar and salutes the American flag at its stern. The 26-year-old has served as the ship’s commanding officer since May of 2018, meaning that, when the ship is underway, she commands a crew of 10 men from the captain’s chair. Easygoing and quick to laugh, Mundy says she leaves a wake of surprise everywhere she goes.

“I guess I don’t portray myself as a hardcore military person,” she admits.

Mundy grew up in Cornwall-On-Hudson, New York, a riverfront village of 3,000 in the shadow of West Point. While attending the U.S. Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut, she “just fell in love with the Coast Guard mission.” Undeterred by the fact that just 15 percent of the Coast Guard’s active-duty force is female, Mundy hit the ground running during her first assignment in Galveston, Texas, receiving all of her qualifications in just six months before being selected to be the only afloat female officer in the Kingdom of Bahrain. When assigned to serve as a commanding officer in Mobile, where some of her male crew members have decades of Coast Guard experience, Mundy says she was never daunted by the task.

“It’s a lot easier than you think, because with the position comes the positional respect and power,” she says. “So they know that the Coast Guard trusts me, the Coast Guard picked me to do this job. Obviously, I’ve earned it, and I’m qualified to do it.”

Notably, the USCG Sector Mobile, which annually conducts over 800 search and rescue cases and consists of over 420 miles of coast, is led by Capt. LaDonn A. Allen, the first female captain of the port for the sector’s area of responsibility. Mundy says that women such as Allen provide an encouraging example to all women considering a career in a male-dominated field.

“If you’re nervous, rise to the occasion,” Mundy says. “If you’re not going to do it, who is? Nobody’s better, faster, stronger than you, but if you let them, they will be.”

Angie Leaver

Owner, Big Bill’s Appliance Repair

Angie Leaver once knocked on the door of a 95-year-old woman who had a broken washing machine. The customer cracked open the door.

“Can I help you?”

“Good morning, I’m here to fix your washer,” Leaver answered.

“You?” she asked skeptically. “Well, come on in. I’ve got to see this.”

Leaver, owner of Big Bill’s Appliance Service in Mobile, laughs at the memory. She says that after 20 years at the helm of the appliance repair business, such encounters are much less frequent. The word has spread about the female repair technician, although there are still clients who expect to find someone matching the description of “Big Bill” on their doorstep.

“Bill was my father,” Leaver explains. “He was a red-headed Yankee, 5-foot-11, 250 pounds. He looked just like the old Maytag Man.” Big Bill started his business in 1989, and it wasn’t long before he began taking his daughter along on service calls.

“My dad expected a lot of us and often passed out pieces of advice. One thing he always said was, ‘There’s three things you never talk about in a customer’s house: religion, politics and Alabama and Auburn football.’”

When he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, Leaver began taking on more of the responsibility. When her father died two years later, she decided, at 24, to carry on his legacy — under the Big Bill banner.

“Keeping the business name was a no-brainer for me,” Leaver says. Twenty years and “a lot of trial-and-error” later, Leaver and her mother, Ronnie, have carried the business to new heights.

“My mom and I are the only repairwomen in Mobile that I know of,” Leaver says. “It’s completely male-dominated.” Whether as a result of her reputation or a sign of changing attitudes, Leaver says she’s witnessed a lot of the skepticism towards repairwomen melt away in the past 10 years. “Ten years ago, I got it a lot. People assumed that, because I’m a woman, I couldn’t repair something or that I couldn’t pick up a washer or throw around a stove.”

Averaging 15 to 18 service calls a day, often with her 27-year-old son in tow, Leaver hardly stands still, but she likes it that way. “I’m trying to keep that legacy going and trying to show my children that you can do whatever you want to do. You’re not limited. You limit yourself, but you’re not limited.”

Alexa Stabler

Sports Agent at Stabler Sports

Representing her father, Kenny Stabler, at the 2016 Pro Football Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony was a jumble of emotions for Alexa Stabler. The legendary Alabama and Oakland Raiders quarterback had passed away 13 months prior, and, despite the tremendous honor of the occasion, his daughter was still grappling with the loss. She had watched his body breakdown as a result of 15 seasons in the NFL and, just months earlier, doctors at Boston University had confirmed that Stabler’s brain exhibited all the signs of CTE, a degenerative brain disease caused by repeated head trauma. Had he not died of colon cancer, they concluded, he almost certainly would have developed dementia.

“I was dealing with a lot of negative emotion — anger to some extent,” Stabler says. “I decided I needed to do something positive with those feelings.”

In her office at Stabler Sports, the agency she subsequently founded in 2017 on lower Dauphin Street, Stabler sits at her desk among commemorative footballs and photographs with her father. The building also serves as the headquarters for AdamsIP, the intellectual property and business law firm started by her husband, Hunter Adams, for which Stabler also works as a trademark attorney. With the conclusion of the 2020 Senior Bowl just days earlier, much of Stabler’s attention is focused on April’s NFL draft.

“This year I have two players who are draft-eligible,” she says, “so my job is to help them get ready for their pro days or different events they’re attending.”

Although only 5 percent of sports agents are female, people who know the Orange Beach native and Alabama Law School graduate say the job is a natural fit, combining her legal knowledge with her unique perspective on professional football.

“I thought perhaps I could use that knowledge and experience on behalf of younger players to help prevent some of the things I saw my dad go through,” Stabler says. “My dad is the entire reason I do this. Additionally, the way my dad raised my sister and me, gender was never even a topic. Now, I see that it was tremendously valuable for me to go into life without a ‘me versus the boys’ mentality. Growing up with that mindset, I’m just not daunted by being a woman in this industry.”

Janet Nodar

Senior Editor, Journal of Commerce

On a hook in Janet Nodar’s office hangs dozens of name badges in every color, souvenirs from breakbulk shipping shows around the globe. While her current role as a senior editor of project and heavy lift at the Journal of Commerce (JoC) doesn’t require nearly as much international travel as her six years as a content director for Breakbulk Magazine, Nodar fondly looks back on her exciting, yet exhausting, travels in the name of breakbulk shipping.

“Breakbulk is a very small niche of the shipping industry,” Nodar says, describing the cargo as oversized or overweight and often related to capital projects. As a result, breakbulk cargo is not shipped in containers and has to be handled with very specialized equipment. “I was in the right place at the right time to learn about it, and it became my specialty to write about it,” she says.

Nodar, wife of WKRG meteorologist John Nodar, says she’s “always been a writer,” but it wasn’t until she began working as a freelancer for Alabama Seaport magazine that the world of cargo came alive for the journalist.

“It was so interesting to me,” she says, “the movement of cargo around the world and how everything interrelates.” With an undergraduate degree in finance, Nodar has always been business-minded, and a master’s degree in English helps put the finishing flourish on her reporting. Now, as the only female senior editor who’s a subject matter expert at the JoC, Nodar says she enjoys the challenge of speaking with shipping experts and making their jobs understandable for an audience. “In other words, using my skillset to bring their skillsets to the page,” she explains.

While those in the shipping industry, and those who write about it, are overwhelmingly male, Nodar says she has “never, that I know of, been treated differently because I was female.” What matters most, she says, is “if you’re fair and if you treat people well.” Nevertheless, for women, and for writers in general, Nodar stresses preparation.

“There were people that would not have been patient with me if I hadn’t done my homework — men and women, but mostly men because there are so many in the industry. But if I demonstrated that I knew at least a little bit, if I could understand their vocabulary and I could understand what they were trying to say, that went a long way.”