At a Dauphin Street dive bar recently, I stood tableside and watched my buddy close out yet another pool victory. Eight ball, side pocket. His opponent glowered toward the stained felt. Now faced with buying the next round, he dug deep to find words with barbs that would sting. “Well, ” he finally said, “I’d still wear y’all out on the tennis court.”

Even on Friday night, tennis is serious business on Mobile Bay. Other evenings, especially league nights, hundreds of players pour onto the courts by Municipal Park, above, to benefit their cardiovascular systems, as well as their social lives. “You can’t get a court sometimes, ” says Tommy Magruder, a local tennis official. “And there are 60 courts.” Tennis has become big business on the Bay as well, contributing millions of dollars to local economies each year, but the country club sport wasn’t always so booming in these parts.

Planting Roots

Magruder has just returned from a weekend of traveling across the state of Mississippi, then over to Huntsville and down to Birmingham, all in the name of tennis. The 72-year-old Mobile native officiates matches 12 months of the year and serves as a trainer evaluator for the United States Tennis Association (USTA). With umpire-chair posture and focus even while his seat is planted on the ground, he looks like just the type of person Johnny McEnroe might want a word with. Magruder retraces the history of Mobile tennis as though it was his own life story, and in some ways it is. He began playing in the city 60 years ago.

Magruder easily rattles off each public court from the Mobile of his childhood. Lyons Park had five hard courts. “They were actual cement, ” he notes. “The way they were laid out, the seams went right down the middle of the court. Some of them had sunk over time, so you might’ve had a quarter of an inch break right down the middle.” Baltimore Park had four, and Crawford Park on Ann Street had four clay-based, rubico courts. “There were no such thing as lighted courts in those days, so all your tennis was played in the daytime.”

The gameplay itself was different as well in those days, Magruder explains. Most points lacked extended volleys and were usually decided by just a few strokes, a primitive style enacted with archaic equipment. He can still recall nearly every player who used those narrow, wooden rackets to rise through the tennis ranks of Mobile and is sure to note one of the first and best, a player before his time, Murphy graduate J.C. Sanford. Though Magruder only met Sanford after his playing days were finished, he sums up the lefty’s prowess through one memento from the 1940s. “There was a telegram, among all of his old stuff, from Bill Tilden (three-time Wimbledon champion and the world’s top-ranked player in 1920), inviting him to New York to play an exhibition tennis match. That’s how good he was – one of the best players ever to come out of Mobile.”

Tennis coaching legend Nick Bollettieri (front row, far right) poses with his 1953 Spring Hill College teammates.

Photo courtesy of Spring Hill College Archives.

With Sanford’s success as a catalyst, the sport’s growth period in Mobile would occur during the relative peace of the 1950s. Another Murphy graduate, Walter Lawson, dominated the city tournaments for years before the teams at all-boys schools UMS and McGill began producing their own stars. Magruder, with fellow Yellow Jackets like Newton Cox Jr. and Tommy Langan, helped establish McGill’s program as the state powerhouse that claimed the James Donaghey Trophy at the Mobile city championships all four years he attended the school.

Around that time, Lucy Masterson was named the pro at the Country Club of Mobile. Masterson, who reached No. 2 in the Southern Lawn Tennis Association, moved from Rochester, N.Y., in May 1945, to play the game year-round. Spring Hill College’s 1953 team boasted its own talented New Yorker, Nick Bollettieri, who would go on to found the famous Nick Bollettieri Tennis Academy in Bradenton, Fla. and become one of the most successful tennis coaches of all time. (Andre Agassi, Monica Seles and the Williams sisters are just a few of Bollettieri’s notable students.) The Bay’s sweltering summers, instead of intimidating those inclined to sweat in the sun all day, were attracting some of the sport’s most dedicated players.

Time to Upgrade

The growth brought with it the need for change in Mobile’s tennis merchandising and infrastructure, but private racquet clubs like Mirror Lake and Oakwood would not be founded until the early 1970s. “Newt Cox used to sell tennis equipment out of the trunk of his car, ” Magruder says, with a grin. “He had a little shop in his backyard in Toulminville where he would string rackets and keep all of his equipment. If you wanted tennis balls or shorts or shirts, anything like that, you could buy it from Newt.”

Then, in 1958, Mobile’s three-seat city council approved the construction of eight tennis courts at Municipal Park. The Mobile Tennis Center was founded through the determined work of people like Cox, who retired from the Army Corps of Engineers to become the Center’s first pro; the Langan and Weinacker families; Magruder and his wife, Claire; Reggie Copeland and many others.

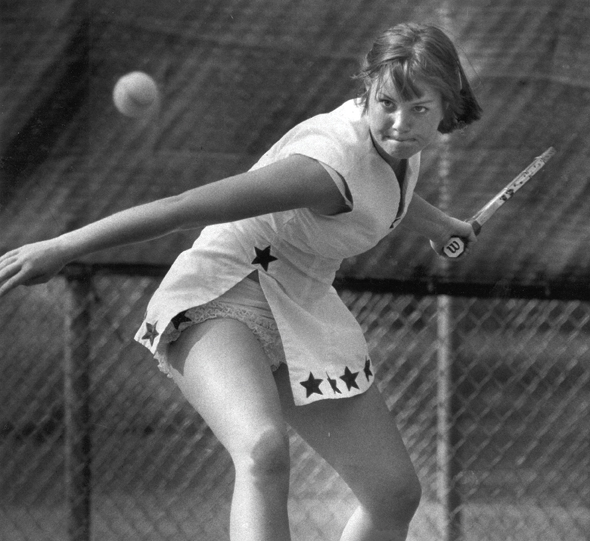

LEFT A 1952 Labor Day tennis match wraps up at Country Club of Mobile. Doy Leale McCall Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

RIGHT Janie Palmer Hazlewood keeps her eye on the ball at Mirror Lake Racquet Club in the 1970s.

In addition to the eight new courts, Magruder says, “We had a pavilion, a water fountain and two restrooms. It was such an improvement that we were tickled to death.”

The complex grew in 36-foot-by-78-foot rectangles, tennis courts pieced together like giant floor tiles. Within a few decades, the site had 34 courts with outdoor lights.

That number hit 50 a few years later, and just a decade ago, the center laid 10 additional courts and staked its claim as the largest public tennis facility in the world. Today, the Copeland-Cox Tennis Center hosts 15 major tourna-ments a year, ranging from the USTA’s Southern Section Championships to the National Christian College Athletic Association Championship.

For the city and its businesses, those tournaments translate into major bucks. Players and their families – 20, 000 to 30, 000 people a year, according to Magruder – carb-load at Airport Boulevard establishments, occupy downtown hotel beds and refuel their cars at local gas pumps. The city economy is not the only institution profiting from a native love for tennis, however, as Mobile’s many organizations and charities have also tapped into the game.

The seventh-annual Serve It Up with Love Tournament, held by the Mobile Child Advocacy Center in April 2012, was named the charity event of the year by the USTA of Alabama. Victory Health Partners’ Let Love Serve Tennis Tournament is a successful fundraiser now in its fifth year. In 2011, professional tennis players Andy Roddick, Mardy Fish and brothers Bob and Mike Bryan appeared at the Mobile Civic Center to raise funds for Distinguished Young Women. Seven years prior to that, Roddick played Agassi in the same event, the Gulf Coast Tennis Challenge, and attracted nearly 9, 000 fans to South Alabama’s Mitchell Center.

At the more recent exhibition, master of ceremonies Murphy Jensen, host of the Tennis Channel’s “Murphy’s Guide, ” referred to Mobile as a “mecca of tennis” and “a great tennis town.” Mobile native Jimmy Weinacker and his son Jay, six-time national father-son tennis champions now living in Birmingham, faced off with the legendary Bryan twins in doubles. The younger Weinacker recorded an ace against the longtime top-ranked duo with his first serve.

Jimmy and his mother, Marcia, are two of 10 Mobile-area tennis players to be inducted into the Alabama Tennis Foundation Hall of Fame. Like the family of former Skyline Country Club pro Joe King – whose daughter, Elaine Campbell, was one of the first female players at South Alabama and now coaches at Cottage Hill Park with her brother, Bruce – the Weinackers are an example of an old sports stereotype: the tennis family. “They used to joke about how Marcia would load up all the kids in the car and take them to tennis tournaments, ” Magruder recalls.

“It seemed like every time you were playing her, she was pregnant. And she would play until the day she delivered.”

Here to Stay

While the Mobile Tennis Center is cause for celebration of the city’s tennis, Magruder voices a handful of worries about the complex. He notes that some of the courts are more than 50 years old. He uses the word “dire” more than once and says a lack of sufficient indoor facilities is costing the city money. The Civic Center’s three indoor courts are not enough to attract additional tournaments, he says, nor do they prevent local college teams from having to forfeit rained-out matches.

But, his fears are temporarily abated with amazement at how popular tennis has become. A recent study by Dr. Phil Forbus, an associate professor of economics and finance at the University of South Alabama, estimates that the Tennis Center had an impact totaling $54, 122, 102 in 2012. While not exactly Mardi Gras (which has been estimated to bring in $408 million), tennis serves up a sizable portion of the Bay’s economy.

“Back in the ’50s, we might’ve had 20 to 30 adults who played tennis in Mobile on a regular basis. Now, I would say there are thousands. Tennis is a big thing, and the facilities have a lot to do with it.”

text by Ellis Metz