Exactly 75 years ago this spring, in May and June 1945, Mobile native and U.S. Marine Corps PFC Eugene Bondurant Sledge was fighting on Okinawa as a mortarman with Company K, 3rd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment of the 1st Marine Division. Sledge was already a combat veteran by this time, having received his baptism of fire on Peleliu in September and October 1944. He was 21 years old.

Years later, Sledge described the fighting on Okinawa in mid-May 1945 and the recurring nightmares that it inspired. “The increasing dread of going back into action obsessed me,” he wrote. “It became the subject of the most tortuous and persistent of all the ghastly war nightmares that have haunted me for many, many years. The dream is always the same, going back up to the lines during the bloody, muddy month of May on Okinawa. It remains blurred and vague, but occasionally still comes, even after the nightmares about the shock and violence of Peleliu have faded and been lifted from me like a curse.”

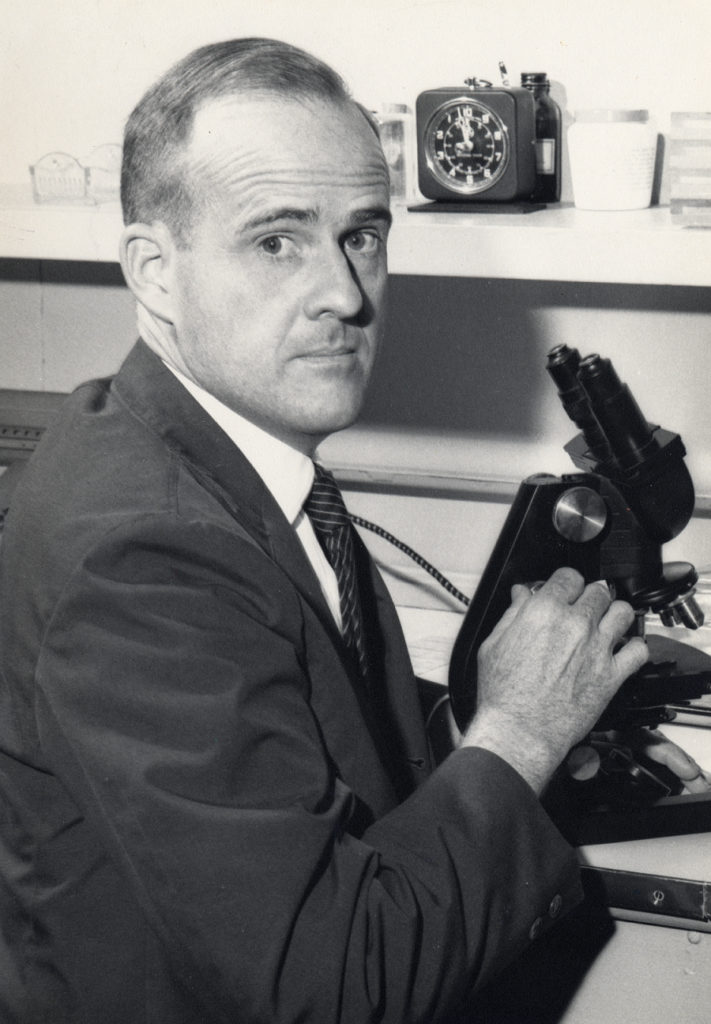

Nightmares haunted Sledge for decades after the war: as a combat veteran and student attending Alabama Polytechnic Institute (Auburn University) on the G.I. Bill in the late 1940s; as a young husband and father pursuing graduate degrees at API and the University of Florida in the late 1950s; and as a professor of biology at the University of Montevallo from the 1960s through the 1980s. Over time, Sledge discovered four things that helped to keep the nightmares at bay: classical music, especially Mozart; literature, especially 20th-century English poetry; scientific research; and the close observation of the natural world and its creatures, which he shared with generations of students at Montevallo.

And writing. During his division’s rest period on the island of Pavuvu after the battle of Peleliu, Sledge began putting together notes he had kept in a pocket copy of the New Testament. Thirty years later, at his wife Jeanne’s suggestion, Sledge used those notes and notes he took during the battle of Okinawa to write “With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa,” his now-famous memoir of the Pacific war. First published in 1981 by a small scholarly press specializing in military history, “WTOB” is recognized today as an American classic. It inspired a Ken Burns documentary on World War II, as well as an HBO miniseries, and has been praised by military historians and literary scholars from John Keegan and Victor Davis Hanson to Paul Fussell. Sledge’s second memoir, “China Marine,” was published in 2002, the year after his death. It describes Sledge’s postwar occupation duty in Beijing, China, and his difficult return to civilian life in Mobile. In addition to nightmares, the war left Sledge with an aversion to violence and killing (a crack shot as a boy, he gave up hunting after the war) and a jaundiced view of overseas military entanglements.

If Peleliu was the dividing line in Sledge’s life, Mobile was its lodestone. Born in 1923, Sledge was the younger son of Dr. Edward Simmons Sledge and Mary Frank Sturdivant Sledge. Sledge’s father was a prominent Mobile physician who was elected president of the Medical Association of the State of Alabama in the late 1930s. Sledge’s mother was from an influential Selma family; his maternal grandmother, Ellen Rush Sturdivant, was the dean of women at Huntingdon College in Montgomery. Sledge grew up in Georgia Cottage, an 1840 Greek Revival house on Springhill Avenue previously occupied by 19th-century novelist Augusta Evans Wilson. By Depression standards, Sledge and his friends enjoyed a privileged life of fathers with professional jobs in the city, mothers who presided over comfortable upper-middle-class homes in the leafy neighborhoods off Government and Dauphin streets, African-American servants and family retainers, and pastimes that included deer and dove hunting on private estates in the Mobile-Tensaw Delta and squirrel hunting in Baldwin County.

The Mobile of Sledge’s boyhood was a small port city of fewer than 80,000 inhabitants. Young Eugene’s world revolved around his home at Georgia Cottage, the family’s dogs — Deacon, Captain and Lady — and his horse, Cricket, his circle of friends at Murphy High School, and the maze of creeks and tributaries in the estuary country around the Mobile River and Mobile Bay, the area described by his son John in his book “The Mobile River.” Two of Sledge’s great-grandfathers had served as Confederate officers during the Civil War. Like many Southern boys, Sledge was fascinated by that conflict. He collected Civil War-era firearms and uniforms, which he kept in a “treasure room” at Georgia Cottage and used in Civil War reenactments with his friends. His favorite pastime was hunting for Civil War relics — Minié balls, shell fragments, buckles and other kit — on the 1865 battlefields at Blakeley and Spanish Fort.

To his father, young Eugene was “Fritz.” To his friends and classmates at Murphy High School — W. O. Brown, George W. Edgar (“Cigar”), Nicholas Holmes Jr., “Chibby” Smith and others — he was “Slag.” To his best friend Sidney Phillips, who grew up on Monterey Place and whose father became the principal of Murphy High the year Eugene graduated, he was “Ugin.” That changed to “Cobber Ugin” after Phillips returned to Mobile from the Pacific in August 1944 after serving with the 1st Marine Division at Guadalcanal and Cape Gloucester and picking up Australian military slang. Back home, Phillips tried to keep his best friend’s spirits up by sending him packets of heavily annotated photos of Georgia Cottage, Ashland Place, the old Cochrane Bridge and their favorite Civil War hunting grounds. Recalling one of their prospecting expeditions on a photo from February 1945, Phillips wrote: “We will have to make up for lost time Cob. The old Land seemed to me to be glad to see me and every stump asked where is Ugin. I told em you’re a comin.” Phillips also touched on the difficulty of explaining to family members what life on the front line was like. On the back of a photo from August 1944, Phillips wrote: “As I was saying about the letters, Ugin, I think even my family used to get a little mad when I didn’t write, but [I] explained it over and over to your folks how the shooting is short and furious, but the shit is long and hard.” Filled with in-group lingo and references to their days at Murphy High, Phillips’ 1944-1945 photos of Mobile and its environs testify to the importance of home and prewar landmarks and pastimes to these young combat veterans of the Pacific war.

Leafing through the letters, photographs and family memorabilia in the Eugene B. Sledge Papers at the Auburn University Libraries is an elegiac experience. World War II has faded from the national memory. The men and women who fought it on the front lines and endured it on the home front are almost entirely gone. Eugene Sledge died in 2001; Sid Phillips in 2015; Nick Holmes Jr. in 2016; and George W. Edgar in 2017. The world they grew up in vanished a long time ago. The world they built for themselves and their children in the decades after the war has been replaced by a world of greater mobility and personal freedom, but also weakened connections to family and place.

Eugene Sledge is famous today as a combat Marine, but that was only part of who he was. It may not have been the most important part. In his son John’s words, Sledge was “a simple scientist with a love of the natural world, who had endured something unspeakable and wanted to convey that to later times and other people.” In a 2014 piece for this magazine, John described how his father started writing a memoir about his Port City boyhood and love of natural history shortly before he died. The unfinished manuscript was entitled “Recollections of a Zoologist.” At the end of his life, fighting the cancer that eventually claimed him, Sledge turned away from his memories of carnage and cruelty in far-off places and returned to the Mobile of his boyhood and its gentle inhabitants, including the common English Sparrow. The naturalist and teacher had the last say.

About “With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa”

It took Eugene Sledge over 30 years to write “With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa,” his memoir of the Pacific War. Sledge kept clandestine handwritten notes during the fighting on Peleliu and Okinawa in the margins of a pocket edition of the New Testament that he had been issued during his stateside training. He began organizing his notes in late 1944, while in a rear-area rest camp between battles. By 1946, he had drawn up an outline of what would eventually become “With the Old Breed.” He put these materials aside to focus on marriage, family and career, but returned to them in the late 1970s. An early typescript shows that the book’s original working title was “Into the Abyss” — an accurate description of its contents. According to his son, John, Sledge wrote “With the Old Breed” at high speed, as if he were “taking dictation,” and would get up in the middle of the night to work on it.

“With the Old Breed” was published by the Presidio Press in 1981. It soon came to the attention of British military historian John Keegan, who referred to it as “one of the most arresting documents in war literature.” Other plaudits followed. In the almost 40 years since its publication, “With the Old Breed” has become an American classic. What distinguishes “With the Old Breed” from dozens of other war memoirs is its clinical honesty and the author’s sensitivity. As Dwight Garner put it in a 2017 appreciation for The New York Times, Sledge “is a gentle man who learns to comprehend hatred.” The result is a uniquely affecting testament to what Dwight Eisenhower called “the horror and the lingering sadness of war.”

Aaron Trehub is the assistant dean for technology and research support at the Auburn University Libraries.