Ken Eslava turns over a square piece of wood, once the lid of a Stauter Boat’s live well, and tilts it in his hands for a better view.

“Do you see any evidence of anythi — yep, there it is,” he says, pointing out a faint scrawl of pencil. “Let’s carry it into the light, see what we can see.”

In the sun outside Eslava’s Fairhope workshop, the marking becomes defined: 66037. Eslava, middle-aged and endlessly friendly, explains how to read the serial numbers on these early Stauters. The first two digits represent the year the boat was built, he says. The remaining three indicate the boat’s position in the order of construction. This piece, then, came off the 37th Stauter built in 1966. Builder Lawrence Stauter always burned a boat’s serial number into the transom brace, located at the stern, but that isn’t the only place Eslava finds the identifier.

“To keep thieves from taking a boat and changing out that brace, Mr. Stauter would write the serial number of that boat in some hidden spots, always in pencil,” Eslava says. “Most Stauter owners don’t have a clue that this exists.”

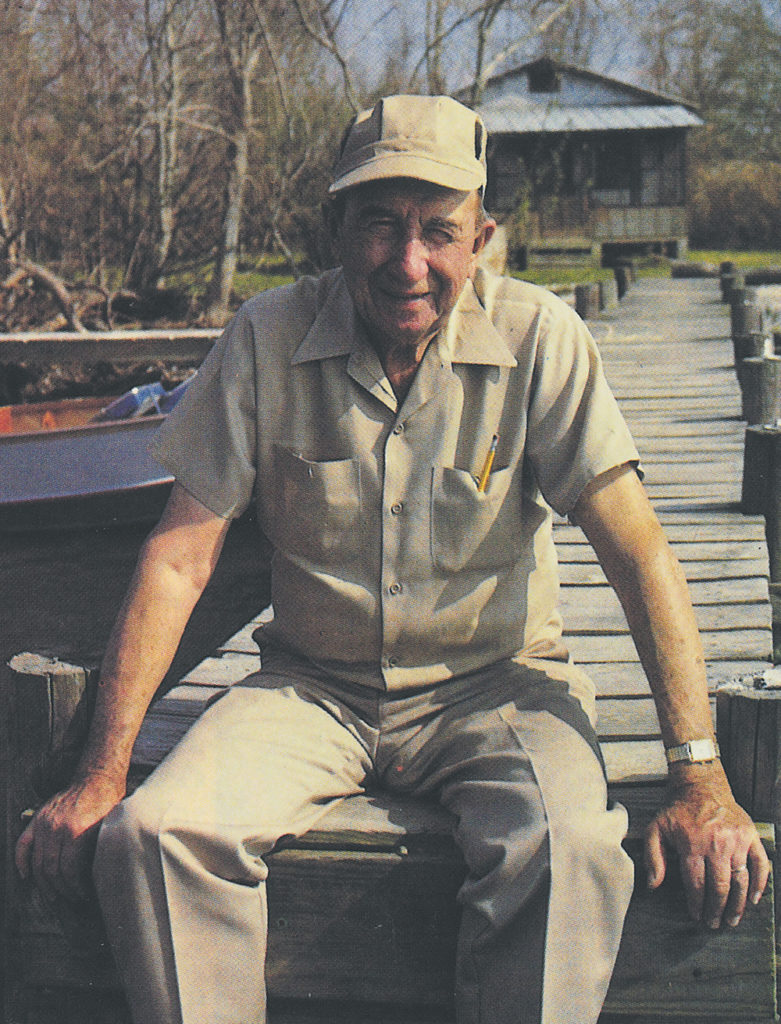

Eslava, owner of Wooden Boat Restoration, loves getting into the weeds about Stauter-built serial numbers. He’s been restoring the legendary wooden boats full-time for 12 years now, so when I decided to set out to solve perhaps the biggest Stauter riddle of all, Eslava’s workshop seemed like a good place to start. The key to the whole mystery, he says, is the serial number.

When Lawrence Stauter sold Stauter Boatworks to kinfolk in 1979, it was the end of one chapter and the beginning of another. The new owners continued building the now-revered wooden boats to Lawrence’s near-impossible standards, albeit in a new workshop. But in the years since, a whispered question has rippled its way through the passionate ranks of Stauter Boat owners: Who owns the last boat Lawrence Stauter built on the Causeway?

Eslava gives me a good lead. One of his customers, Austin Greene of Fairhope, owns the highest 1979 serial he’s come across: 79100.

“He’s winning the race so far, to my knowledge. I mean, I’ve done hundreds of these boats in the years I’ve worked on them, but any time I see that ’77, ’78, ’79, it’s like, ‘Let me look a little further at this boat.’”

He promises to put me in touch with Greene and wishes me luck on my search. “I’ll be curious to see what else exists.”

Lawrence Stauter was raised beside the brown, languid waters of Conway Creek in the Mobile Delta. From the roof of his home, where he liked to sit as a boy, he could look south clear towards the Gulf of Mexico, before man built the Causeway with its bait shops and restaurants. He could look west towards the Mobile River and across the swampy expanse, where the ancestors of early German settlers — with last names like Stauter, Spattle and Kleinschrodt — eked out a living in homes built on 8-foot pilings. He could look north and see the smoke from distant whiskey stills, tucked into the Delta’s hardest-to-reach crannies.

“Eventually, everybody learned how to make whiskey,” Lawrence told Morry Edwards, a freelance writer for WoodenBoat magazine in 1986. Lence Stauter, however, Lawrence’s father, wasn’t like everybody else. Lence taught his son the finer points of delta living: how to run a trot line, gig frogs, trap turtles — and build boats.

“Daddy was a good mechanic,” Lawrence told Edwards. “He had no schooling. Yet, with nothing but a square and a level, a plane and a hatchet, he could make things fit.”

In the Delta, your boat was your livelihood. It carried the Stauters to church in Mobile, it took Lence up the creek to hunt for hogs, it sped Mrs. Stauter to the doctor when she was bit by a ground rattler and it carried the family to higher ground during a hurricane’s early, crucial hours. On Conway Creek, a family lived and died by its boat.

Upon graduating from high school in 1930, Lawrence found that the Depression left few job prospects, so he returned to Conway Creek to help support his family. The delta lifestyle, he said, was far from some romantic adventure. “There weren’t no damn adventures,” he told Edwards in 1986. “You had to work. In those days, you didn’t do what you preferred; you did what you could.”

Chan Flowers answers the door of his Midtown home with a big smile. He’s parked three of his glistening Stauters in his front yard for my benefit, and he enjoys my admiration. “That’s half of my collection,” he says.

Flowers, I’m told, has fixed up a lot of Stauter-builts over the years and maybe could point me in the right direction. He walks me through his home, which is decorated with plaques and trophies from wooden boat shows across the region. Most of the trophies are for first place.

“People tell me I’m sick,” he jokes.

Flowers estimates that he and his son have bought, restored and sold about 15 Stauters in the past 10 years, often spending hundreds of hours on a single boat. The work, he says, is nothing less than a passion.

“There’s one thing a wooden boat has that a fiberglass boat will never have, and it’s called a soul. Stauters are a local piece of history and art as far as I’m concerned.”

I ask if he’s ever heard someone claim to own the last Lawrence-built Stauter.

“I know 100 people who claim to have the last Stauter,” Flowers says. “A lot of people make the claim, but who knows. Back in the day, when you’d go in there and buy a boat, it was pretty much a cash deal and a handshake. There was probably not a whole lot of serial numbers and documentation.”

“So if I can find the latest serial number in 1979, do you think that’d be a fair way to crown a boat as the last Stauter?” I ask.

“Good luck,” he says, with a big laugh. “Good luck. Who’s to say that boat still exists?”

I decide to pay a visit to maritime historian John Sledge to see if the topic has come up in any of his extensive research. On the back deck of his Fairhope home, Sledge says he’s never personally heard the claim, but he’s not surprised by the mythology that has arisen around Lawrence and his Causeway shop.

“What’s interesting to me about the Stauter phenomenon was that you had that all along the coast, different guys in different places … who specialized in a particular kind of boat that was suitable to whatever their waters were.” He mentions the Lafitte skiffs of Louisiana and the Biloxi Luggers of Mississippi. “Stauter is very much in that tradition of local boat builders kind of perfecting their craft. He really was a master of the environment.”

In 1930, Lawrence, a high school graduate in Conway Creek, decided to start building boats for some pocket money. He charged $25 back then for a 12-foot boat, $35 for a 14-footer. According to WoodenBoat magazine, he built about one vessel a month, profiting around $10 on each one. “And 10 dollahs was a hell of a lot of money in those days,” he said.

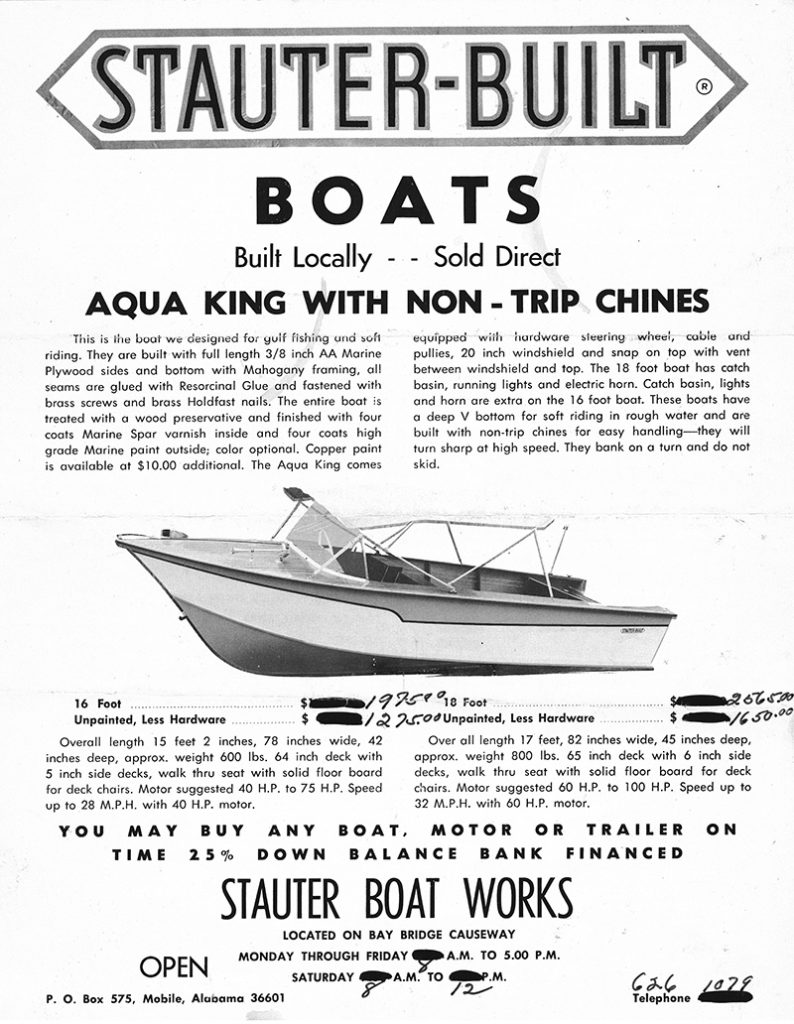

When Lence suffered a stroke and could no longer fish, Lawrence found it necessary to leave the swamp for a construction job in Mobile so he could better support his parents. He worked hard, bought some land and built a home on the Causeway, which at that time lacked drinking water and basic utilities. If that decision doesn’t speak to Lawrence’s foresight, how about this one: Looking ahead to the conclusion of World War II, Lawrence predicted a need for returning soldiers to relax on the water. They’d want boats, and Lawrence knew how to make them. He built a workshop behind his Causeway home and, in 1946, quit his job.

“People thought I was crazy,” he told Edwards. “I dropped from 85 to 50 dollahs a week. But that was alright. I was happy with what I was doing. As far as making lots of money, I never had anything all my life, so hell, if I made a living, I thought that’s all I was s’posed to have.”

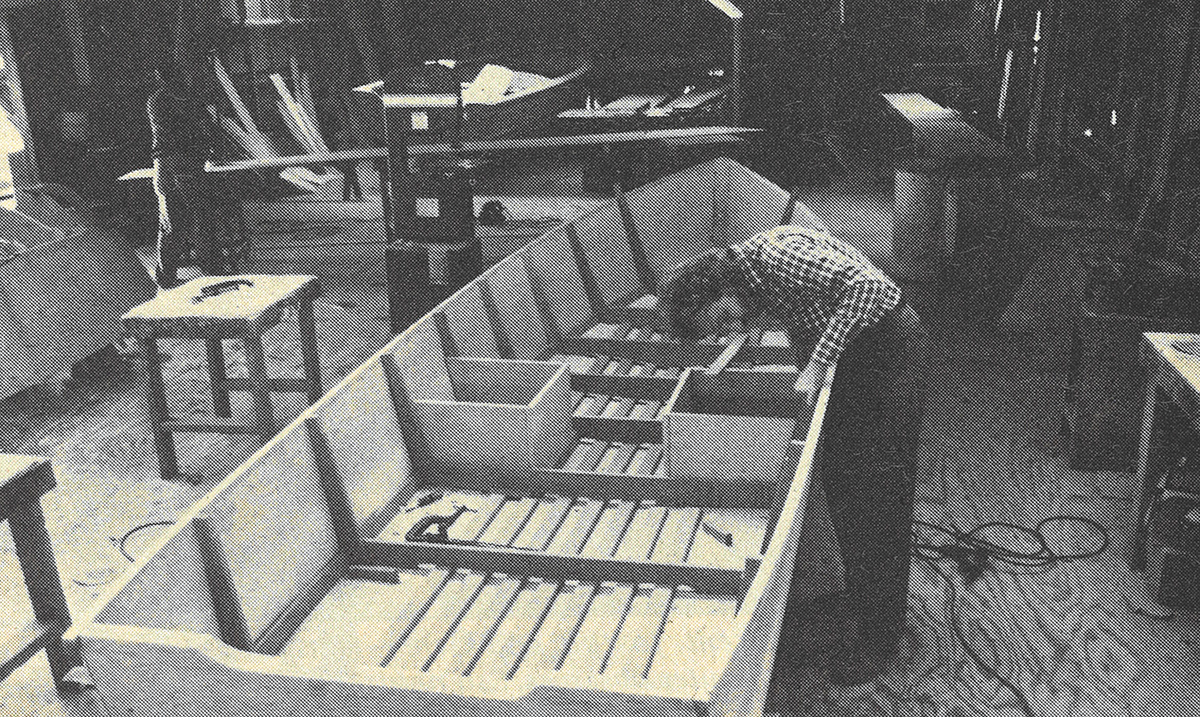

Stauter-built boats were an immediate success. By the end of his second year, Lawrence and his crew of eight were turning out 30 boats a month. At its peak, Stauter Boatworks would build an astounding 400 vessels a year. Aside from his insistence on quality, Lawrence was also known for his booming laugh, which could be heard, many joked, from one end of the Causeway to the other.

Lawrence was used to hurricanes; he had watched his father prepare for the storms on Conway Creek and had lived through more than a few on the Causeway. But Hurricane Frederic was different. The day before Frederic’s landfall in September 1979, Lawrence packed up his shop, called some customers to fetch their unfinished boats, moved his supplies to higher ground and went to bed early at the home of some relatives. When his wife went upstairs later in the night, she found her husband awake, listening to the wind.

“Stauter Boatworks is gone to hell,” he told her. “That tin building over there has disintegrated, and the water’s gonna come after a while and wash the whole thing away.” Once again, Lawrence Stauter’s foresight proved true.

Austin Greene pulls back the fabric boat cover to reveal his Stauter’s serial number: 79100. Greene bought the 16-foot bait boat in 2017 from Pete Burns, the boat’s original owner. According to Burns, Lawrence called the day before Frederic made landfall and urged him to come pick up the unpainted, engine-less boat before the hurricane blew it off the map. “I mean, it was in the earliest stages of production,” Greene says of the aptly named Last Call. As for Lawrence’s records? Greene says that, to his knowledge, all serial numbers and documents were swept away with the shop.

During our conversation, Greene remembers an encounter he had on Fish River with a man who claimed to have assisted Lawrence after the storm with retrieving unfinished boats that had been swept into the Delta. For the man’s trouble, Lawrence allowed him to keep one of them. It’s a new wrinkle to the mystery but one that won’t be ironed out.

“I wish I could give you a lead there,” Greene says, struggling to remember the man’s name. “I think that’s the most interesting thing about these boats. There’s such an interesting culture around them, because it’s all word of mouth. It’s basically storytelling that’s keeping the history of all of this alive.”

Mobilian Gin Mathers is the owner of a 15-and-a-half-foot Cedar Point Special with a similar “Frederic” history. Her father, the boat’s original owner, picked up his unpainted Stauter the day before landfall. It makes me wonder, How many phone calls did Lawrence make that day?

Interestingly, Mathers’s boat has a serial number of 78101, which doesn’t align with the 1979 landfall of Frederic. But it’s possible, I’m later told, that the boat was simply outfitted with a leftover 1978 transom brace.

Suddenly, the answer to my question seems further out of reach than ever before.

On the Causeway after the storm, Lawrence found nothing more than a series of snapped pilings where his home and workshop once stood, so at 68 years old, he decided it was time to retire. Four months later, in January 1980, Stauter Boatworks reopened off Three Notch Road under the ownership of Gene, Joseph and Vince Lami, the grandsons of Lawrence’s first cousin and Delta neighbor, Frank Kleinschrodt.

Lawrence’s advice to the new owners? “Hold your quality,” he said, “and don’t let your price run away. The reputation is there, the business is well-established. You don’t have to worry about a darn thing.”

I call Tom Lami, who has recently bought the Stauter-built name, boat patterns and trademark logos from Gene and Vince Lami (his father and uncle, respectively) with the intention to restart production. Gene and Vince ceased the construction of new Stauter Boats in 2010. As for claims about owning the last Lawrence-built Stauter?

“We hear that all the time. And honestly, I hate to disappoint you, but that is a mystery and will probably remain a mystery because of the fact of what happened to the business there on the Causeway. There were a handful of boats that were still under construction.” As for a collection of records that might still exist? “Mr. Stauter either lost that in the storm or never kept it.”

Furthermore, Tom says, even if two boat owners compare their similar serial numbers, there’s no guarantee that a higher serial number means a later date of completion.

As press time rapidly approaches, I’m put in touch with retiree Richard Craig. “Lawrence was my great-uncle,” he tells me over the phone. The serial number of his Cedar Point Special? 79108.

“The boat was just about finished,” Craig says. “It was in the paint shop, a two-story building at the northern end of his property on the Causeway.” As the storm surge smashed Lawrence’s home and workshop into the pilings of the Bayway, which had opened just the previous year, Craig’s boat somehow managed to ride out the storm, relatively undamaged.

“Lawrence was going [into the Delta] every day, just up there looking around, trying to find what he could find, what he could salvage. And he found the boat.”

Craig’s story is reminiscent of what Greene had told me — that some mystery man was gifted a Stauter Boat for helping Lawrence in the storm’s aftermath. I ask how many boats Lawrence might’ve pulled out of the Delta.

“It was my impression that [my boat] was the only one he found,” Craig says. “I couldn’t say that for an absolute fact, I just don’t remember him ever talking about that.”

I ask Craig if he’s ever come across a higher 1979 serial number than his own. “Oh no,” he says. “That’s the last one that was built in that shop, for sure. ‘Cause it was in the paint shop being finished the night of the hurricane.”

The story of Craig’s Stauter raises an interesting question: With so many unfinished boats on the property that day, in various stages of construction, can any of them claim beyond a doubt to be the last Causeway Stauter? And if you were to compare two of those unfinished boats, would their serial numbers, assigned at purchase, really be the fairest way to make a conclusion?

I drive out to Stauter Boatworks itself, a yellow, metal building down Three Notch Road on the site where the Lami brothers set up shop back in 1980. Today, the brothers sell and repair trailer parts and Tohatsu outboard motors.

“Everybody wants to believe that they have the last Stauter that came out of the shop [on the Causeway],” Vince says. “Truth be known, some of the last Stauters built were probably never found — up in the Delta, you know!”

“What do you think about this quest of mine to find the last Causeway Stauter?” I ask. Gene laughs softly.

“That’s going to be an impossible task. It’ll never happen. There’s going to be so many people claiming they have the last Stauter off the Causeway, and there’s just no way of knowing.”

I tell them about the boats I’ve found. Austin Greene’s 79100. Richard Craig’s 79108. “There were boats after that,” Gene says confidently. “‘Cause I bought one in 1973. It’s 73196, and I got it in November.”

“So it’d probably be beyond 125 or 150,” Vince says.

“Oh, yeah. I would think,” Gene agrees.

The Lami brothers also confirm a tidbit I’d heard along the way. The last Stauter that Lawrence ever built? He kept it for himself.

“After we got the business,” Gene says, “he moved to the corner of Senator Street and Morgan Avenue down at the Loop. He had a garage … and he built a 15-and-a-half-foot Cedar Point Special in that garage. His nephew owns that, Butch Taylor. That’s the last boat Mr. Stauter built. Definitely.”

That’s a nice word to hear: definitely. And although it’s not the last “Causeway Stauter,” I must admit it’s a poetic conclusion. The “last Stauter” claims and the Hurricane Frederic stories will continue, and I hope they do. Lawrence, who died in 1998, probably would have enjoyed the rumors and intrigue his boats have created. A man with proven foresight, maybe he saw all this coming, too. And so the boat builder with the big laugh made sure he had the last laugh — and the last Stauter.