From the massive Gulf to tiny butterflies, tasty oysters and humble creeks, the Alabama Gulf Coast is our heritage, playground and, for many, a livelihood. Keeping such waterways clean and viable is the responsibility of us all.

Here are eight examples of those who do it right, our 2025 Watershed honorees. Their interests vary from classrooms in waist deep saltwater to respectful awe of an industrial strength river. But their goal is the same: aquatic excellence.

Katie J. Owens

A retired teacher in Mobile County and Baldwin County schools, Katie Owens has taught thousands of children about the importance of our Bay and wetlands. She did so in part as the voice of a frog.

Ribbit’s Big Splash presents interactive, decision-making activities for computers, home and school, and was created by Katie’s father with her assistance. “Dad encouraged me to educate and show children the significance of conservation, the environment and the critters in a puddle of water just outside your door,” recalls Owens. “There was very little local information available for elementary age children on these topics at the time (the 1990s). I was still in high school when I became the voice of Ribbit.”

The program was produced on CD-ROMs. “CDs were big back in the ‘90s,” Owens recalls. Ribbit’s Big Splash was released in 2000. By 2003, over 38,000 Alabama students had used the program.

From Ribbit’s Big Splash, the Coastal Kids Quiz (CKQ) was created. It was coordinated by Owens for elementary school fifth graders. “I ran the CKQ for almost 10 years,” she recalls. “Originally, Coastal Kids Quiz was conducted much like a Scholars Bowl. Each school had fifth grade teams competing.”

The CKQ was reengineered by the Alabama Coastal Foundation (ACF). Owens is on the ACF Board. “Kids see it as a game but they are learning from it,” says the retired teacher, referencing CKQ.

She adds, “Seeing ‘graduates’ of Ribbit’s Big Splash and the CKQ is a thrill. Some are now adults, environmentalists at heart, and doing good things,” she says. “I also love seeing children interacting in these programs, getting the first little pieces about our ecosystem. They may one day find opportunities to help solve problems we do not know about yet.”

Future scientists may one day emerge from children inspired by a computer program, enthused by a Coastal Kids Quiz competition, or guided by the wisdom of a frog named Ribbit.

Michaela Shirley

In northern Mobile County, on the banks of the Tombigbee River, Outokumpu Americas (OTK) produces steel for worldwide customers. The river makes it happen. Michaela Shirley keeps the river clean.

“Actually, protecting the Tombigbee is a team effort,” says Shirley, OTK’s senior environmental sustainability specialist. “My responsibility is to meet environmental compliance, but every employee shares that responsibility.”

Shirley and team strive for more than meeting EPA standards. Their goal is to exceed expectations. “We are not satisfied to make the bare minimum,” she notes. “We strive to be the best.” The best includes good water. “We depend on the Tombigbee to make our products,” Shirley adds. “We must be guardians of the river. We want to work well with the environment and the community. We want to meet the regulations and do better.”

Her team constantly monitors ways to decrease river emissions. Recent projects have reduced OTK’s nitrate discharges by 40%. In one area of the mill, water usage has decreased by five million gallons a year. But the challenges continue. “There are so many regulations – federal, state and local – to keep up with. The challenges and changes occur almost daily but I can make an impact,” she notes, about keeping the steel mill running and the Tombigbee clean.

“It is an important job but also very satisfying. It is a job where you go home at the end of the day with a good feeling of what you have accomplished.” As for working in a major manufacturing site, she adds “I have been here for 13 years. It still amazes me to see how steel is made.” Just add water – Tombigbee water.

Doug Ankersen

One could swim among oyster larvae and not notice as they are not much bigger than a speck. Doug Ankersen, owner and operator of Isle Dauphine Oyster Company, raises such oysters and, as of this writing, has a lot of those “specks in stock” – about 12 to 15 million.

He and wife Mary raise oysters from seed to restaurant ready. He takes oystering to a higher level, literally. His marvel mollusks are raised off-bottom, that is, in floating cages above the Gulf floor. The advantages are many.

“Raised off-bottom, oysters grow faster and cleaner,” he says. “In addition, the oysters are more uniform in size and shape and their food, such as algae, is more prevalent near the water’s surface than underneath on the ocean floor.

Ankersen has been in the business since 2014. He started out as a commercial oyster seed nursery operation. He learned about the floating cages and innovative aquaculture techniques of oyster production, from a class taught at Auburn University.

Isle Dauphine’s oysters obtain food directly from the Dauphin Island seawater they are submerged in. There are no supplemental additives. The oysters grow and are transferred from hatchery to nursery, to farm and then sold to restaurants, farms and other oyster businesses. His customer base includes Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas and Florida.

Off-bottom oystering also helps the environment and its marine life. Part of Ankersen’s shellfish are recyclable as he keeps some of the oysters to provide more seed which will start the cycle over again.

Carmen Flammini

In South Alabama, monarch butterflies get by with a little help from their friends. One such butterfly buddy is Carmen Flammini, Alabama Cooperative Extension System agent, Daphne resident and protector of the monarchy – the one with wings.

She has concerns. “Monarch butterflies are like the canary in the coal mine,” she says, referencing the days when miners sent birds into a dark mine before humans entered. If the canary lived, everything was fine. If the bird died, that was not good.

“Studying the monarch’s population and behavior can indicate how well we are caring for our native ecosystem and whether we are providing adequate food supplies for the insects that depend on it,” she says. “It’s important to maintain our monarch butterfly population. Declines can signal broader threats to pollinators and ecosystem health.”

This cute little bug migrates from Canada to Mexico and back, flying up to 3,000 miles round trip. It can fly over 100 miles in a day.

Flammini’s current project is focused on studying Alabama native milkweed plants, a species that monarch butterflies depend on exclusively to lay their eggs, nourish the caterpillar stage and provide nectar for the adult butterfly. She encourages us to plant more milkweed, but the right kind: the native species are appropriate for our area.

The milkweed project is in conjunction with an Auburn University entomologist, the AU Horticulture and Ornamental Station in Mobile, the Baldwin County Master Gardeners and 10 other organizations in Baldwin County,

“Monarch butterflies are dwindling in number,” she says, “often because their food is dwindling too.” Without the correct nourishment, the butterflies can’t make the trip.

She adds that Alabama Native Milkweed plants also play an important role providing nectar to other pollinators.

Flammini also teaches master gardener classes and is an expert on home grounds, gardens and pests. She has designed STEM garden programs for schools and other local projects.

Flammini’s endeavors benefit home gardeners, the environment, and tiny winged creatures with a flight to catch.

Tom Damson

As a boy, Tom Damson was raised on Dog River. He nostalgically recalls the good ole days when the river provided an abundance of fishing, swimming, and boating, in a watery playground. Life on the water was good back then and Tom strives to keep it that way now.

He is an active member of Partners for Environmental Progress (PEP) and was its board chairman for two years. “We advocate for the environment and best practices in business and manufacturing,” Damson says, about the group with a membership from all points of life. “We have business people and ardent environmentalists in our group. We know that if we communicate, things will work out.”

One of Damson’s and PEP’s current endeavors for a common good is The Eagle Reef Partnership, ‘mini reefs’ for oysters and other creatures. It began as an Eagle Scout service project, hence the name, Eagle Reef. “It is a floating reef in a large box structure, installed under wharfs and other areas,” he adds. “It attracts oysters, barnacles, shellfish. Most importantly, it provides a safe habitat for such marine creatures which have seen population decreases over the years due to less sea grass and habitats.”

He adds, “working with our partners, including the University of South Alabama Stokes School of Marine and Environmental Sciences, PEP Project hopes to deploy a thousand such reefs by the end of 2025. Over 200 are currently installed.”

In addition, Damson is a skilled fundraiser for environmental causes with proceeds going to PEP. He is also an adamant believer that, regardless of one’s statue in life, common ground can be reached. For Damson, that common ground is clean water with vibrant life.

Tom Hutchings

Living shorelines are a dream for some, desired by many and doable for Thomas Hutchings. A native Mobilian, he is president, owner and manager of EcoSolutions Inc. and its sister company, B&B Dredging. Hutchings guards, repairs and restores the life in living shorelines.

He has served in various capacities for the National Marine Fisheries Service, Osprey Construction, Eastern Shore Marine, Southern Yacht Charters, Alabama Coastal Foundation, and Hutchings and Associates.

EcoSolutions opened in 1995. “We recognized a niche not being filled,” Hutchings recalls about the start-up years. It is a niche no more.

He notes, “EcoSolutions designs and permits the project and the sister company, B&B Dredging, builds it.” Don’t try this at home.

“People don’t realize the detail the federal, state and local government puts on you,” Hutchings says, referencing beachfront property owners and those who want to be. “Handling government regulations, environmental laws and other mandates is not something you should do alone.”

He continues, “We work with the customer for the best solution to protect your shoreline while preserving the ecological integrity of the Bay.” He promotes shoreline revitalizations and restorations through the use of natural alternatives such as plants, sand and rocks. “We want to mimic nature as close as we can,” Hutchings adds. “Shoreline creatures are part of the food chain. If we lose that, we break the chain and then we start the downward spiral.”

But it does not have to be like that. “Do not procrastinate,” Hutchings warns about erosion and other factors property owners may face. “Once the shoreline is gone, it is difficult to get it back.”

On a positive note, he proclaims that humans and shorelines can co-exist not just because we need to but because we want to.

Kacie Hardman

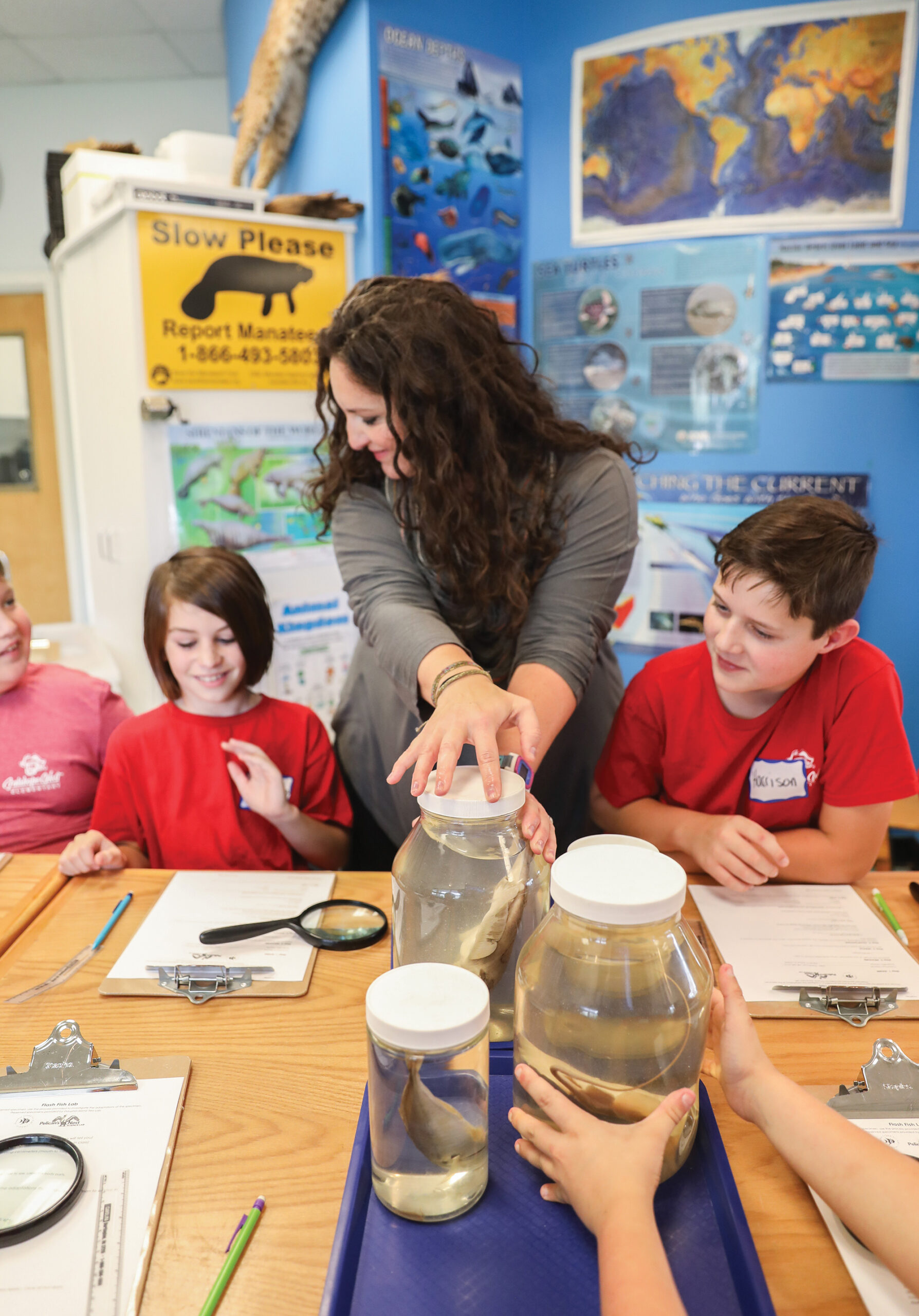

Fairhope’s Pelican’s Nest Science Lab’s website quotes Confucius: “I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.” The Chinese philosopher no doubt referenced Mobile Bay.

Okay, he never visited Mobile Bay, but his words describe the Eastern Shore’s body of water perfectly. Mobile Bay is a hands-on teacher.

Pelican’s Nest Science Lab makes that teaching happen. Kacie Hardman, a teacher in Fairhope West Elementary School, is the Pelican’s Nest Science Lab’s director.

“She explains the rewards of teaching in the waves often waist deep by saying, “When you see the spark in a child’s eyes, while holding a crab about the size of their pinky nail, or viewing plankton under a microscope, and for the first time, understanding what an estuary is, that is just life changing for me.”

A signature program of the Fairhope Educational Enrichment Foundation and the Baldwin County School System, Pelican’s Nest offers K-6th an outdoor classroom onshore and off. In 2025, the nest will be expanded for students K-12 with curriculums for each grade level.

“For many of these students, even kids growing up on the Eastern Shore, it is the first time for getting their toes wet in the bay,” Hardman says. “We present opportunities to touch a fish or toss a cast net for the first time.”

She notes that inquisitive youngsters — especially the elementary grades — have questions. “Some want to know if we will catch whales, great white sharks, or an octopus,” she recalls. “The answer is no.”

But the director adds, “however, whatever they pull up in their nets, even if it is seagrass, excites them. They dig into the seagrass and discover tiny minnows and crabs hiding in it. This appreciation for our waters cannot be taught in a formal classroom or in books. It has to be experienced.”

Avery Bates

In a 2018 interview with Mobile Bay Magazine, Avery Bates explained his profession. “Folks should realize when you see our shrimp boats or oyster skiffs, it is not a fleet,” said the commercial fisherman, about the craft passed down to him through family generations. “Each boat is usually a single local family business, owned by a local person, making a living for his family.”

In 2025, Bates is retired. But his advocacy for commercial fishing is unyielding.

“Everything we buy and have, our land, houses, trucks, cars, comes from our labor” he says, about the men and women who cast nets professionally.

Bates has served as vice president of the Organized Seafood Association of Alabama. “We fought many battles and we still do,” he notes about the group. “Many of us had to shut down because of government regulations.”

He is concerned about the demise of local fish, especially oysters, due to mud and silt unloading. “We witnessed massive amounts of mud dumping in upper Mobile Bay,” he recalls. “You can’t put dirt on top of oysters,” he states. “It suffocates oysters and kills them.”

He notes that mud was dumped on the oyster reefs, destroying their habitat.

Like many in Bayou La Batre, Bates learned his vocation as a boy and stayed with it until retirement. Speaking about his trade he testifies, “This life is not an easy life. Commercial fishing is not an easy job. To do it you must love it.”

Avery Bates loves it.