Photo by Kathy Hicks

We don’t need a list of facts and statistics to tell us that this place is special, but take this into consideration: Mobile Bay is the fourth largest drainage basin by volume in all of North America. To put it another way, every ounce of water that falls west of the Appalachians and east of the Rockies will enter the Gulf of Mexico through the Mississippi and Mobile Bay drainage basins. While the Mississippi catches the majority of that flow, 43 billion gallons of water a day pour into the shallow, broad expanse of Mobile Bay.

But for the past several decades, the same sediment-driven river systems that have made our region so fertile and diverse have also made it vulnerable. The waterways that tumble and flow towards Mobile Bay carry a lot of baggage in the form of runoff pollution. And while a lot of it can come from as far as a state away, some of it comes from our own neighborhoods.

Reily Murphy stands in the backyard of his Fairhope home, admiring the serene waters of Fly Creek. Kayaks and life jackets scatter the grass haphazardly, and he apologizes for the disorder. “We had a ton of family over here this weekend, ” he explains.

A lifelong outdoorsman, Reily adores his Fly Creek home, which he shares with his wife Mitsy. “Here, we’ve got the water, and we’re close to town, ” he says. “We have three boys and a daughter, and my boys live outdoors. So the water was a big selling point — to be able to jump in a boat and go right out to the Bay and fish was huge.”

And that’s exactly what the young family does. Fishing trips in Mobile Bay conclude with dips in the creek, and lazy afternoons in the water become lazy nights on the dock. But three years ago, an incident involving Reily’s youngest son alerted the family to dangers unseen.

“The kids were playing in the creek, ” Reily says, “and our youngest, who was 4 years old at the time, hit his shin on the pier.”

The injury was no more than a scratch, but two days later, when the boy was stuck in bed with a fever, Reily noticed redness and intense swelling on the youngster’s shin. Antibiotics were of little help, and the redness spread to his ankle and knee. When the family was sent to an orthopedic surgeon, the doctor took one look at the boy and admitted him to the hospital.

“They couldn’t determine whether or not it was the water that did it, ” Reily says, “but they felt pretty certain that was the case.” The young boy underwent surgery and eventually got back on his feet, with the help of physical therapy. But the ordeal was an awakening experience for Reily and Mitsy, who walked away with a greater awareness of the local water quality. “We’re definitely more cautious now, ” Reily says. “After the kids swim, it’s immediately to the bath.”

ABOVE “I’m a businessman and a family man. I‘ve never been in a lawsuit before, and that’s about the last thing I would have thought would happen. But I find myself getting more and more involved in the political arena — I don’t want to get involved in politics at all, but at the same time, I want to make sure that the area where my children play and friends come over to play is a safe environment.” – Reily Murphy, Fairhope resident living on Fly Creek

Photo by Matthew Coughlin

As coastal regions around the world grapple with issues surrounding wastewater pollution, we’ve found that Mobile Bay and its surrounding waterways are no exception. Defined as a byproduct of agricultural, industrial or domestic activities, wastewater can both threaten human health and smother ecosystems. Ken Heck, a senior marine scientist at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab, estimates that around half of the grass beds that used to exist in Mobile Bay and coastal Alabama have disappeared. The beds, which serve as a valuable nursery for baby shrimp, crabs, fishes and other Bay critters, are continually robbed of crucial sunlight by the ever murkier waters they inhabit.

But the issue that’s drawn the most attention recently is sewage overflow, 26 million gallons of which entered Mobile Bay in 2017 from spills across Mobile and Baldwin counties (think 39 Olympic-sized pools). On Monday, August 7, of this year, Fairhope Utilities personnel discovered that a malfunction at a wastewater lift station had deposited 266, 250 gallons of raw sewage into Fly Creek. The spill, which had begun three days prior, was triggered by a blown fuse that both shut down the station’s pump and disabled its backup alarm system. As a result, anyone who entered the creek on that summer weekend unknowingly shared the water with raw sewage. The incident reignited public concern over the system’s reliability and capacity.

“Our [sewer] system is so antiquated, ” Reily says. “It was built for a certain population size, but [Fairhope has] doubled in size since then. And that was one of the big concerns with an apartment complex coming in upstream. They’ll be tapping into that same system.”

Despite a suit filed by a handful of Fly Creek residents, including Reily, against the city of Fairhope, construction of a 240-unit apartment complex along Fly Creek is slated to move forward amidst concerns of increased creek pollution. Reily admits he “never would have dreamt” becoming involved in such a lawsuit, “but at the same time, I want to make sure that the area where my children play … is a safe environment, ” he says.

Unfortunately, similar scenes are unfolding in creeks and rivers surrounding Mobile Bay — places like Dog River, Three Mile Creek, Eslava Creek and D’Olive Creek. And in this neck of the woods, all creeks lead to the Bay.

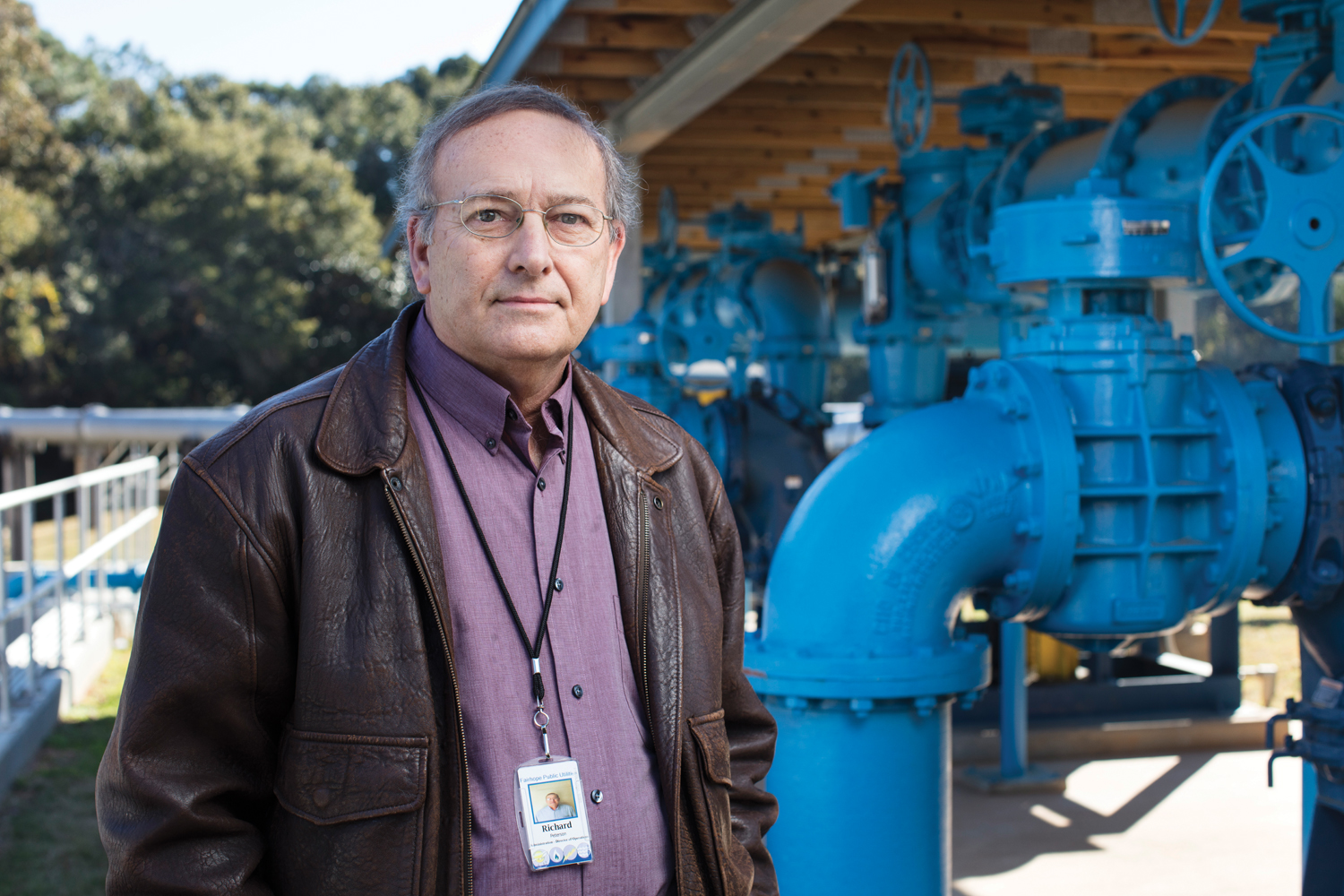

ABOVE “History will document and somehow judge our stewardship of Mobile Bay. Today, I would have to say that we are not being as responsible as we should be to protect the water quality of Mobile Bay for the future generations. That is not to call out any entity for failing to act, but to say we should both individually and collectively find the motivation to support goals for improved water quality.” – Richard Peterson, Director of Operations, City of Fairhope

Photo by Matthew Coughlin

A Growing Problem

At the city of Fairhope’s Wastewater Treatment Plant, Director of Operations Richard Peterson lifts a metal grate to reveal a roaring torrent of water below our feet. After describing the step-by-step process of treating raw sewage, he’s brought me here, to the last stage. Before being piped out 3, 000 feet into Mobile Bay, the treated wastewater passes through an ultraviolet light, a final act of disinfection. The entire process, I come to realize, is actually pretty marvelous.

Peterson is frank about the issues facing the Fairhope treatment plant and other plants on the Eastern Shore. “The biggest hurdle will be how to balance the need to address the aging infrastructure … with the need to improve our capacity to accommodate new growth, ” he says. Baldwin County is the fastest growing county in the state, having added 26, 298 people from 2010 to 2016 — a rate of 12 newcomers a day. The simple fact is that the capacity of the existing sewer system is being pushed beyond its limit.

Peterson has helped create meaningful conversation throughout Fairhope with his inventive, outside-the-box ideas about combating the city’s sewage issues. One such suggestion is the establishment of “satellite wastewater treatment facilities located near golf courses or areas with high irrigation demand. This can allow us an opportunity to preserve the potable water resources used for irrigation and replace it with ‘reuse quality’ wastewater effluent.”

Other proposals Peterson has made to the city of Fairhope include the creation of a crew to continually assess the condition of and make repairs on the wastewater system. “We should also further develop the plant’s Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition system, which allows the utility plant to create maintenance alarms for abnormal conditions found in the data.” His recommendations include spending $4 million in the next three years to address sewage issues. “This proposed investment in the rehabilitation and upgrade of the system requires a rate increase for homeowners and a connection fee increase for new customers, ” Peterson says. Such a financial commitment, he says, is “required by the community to make significant progress” on the wastewater problems.

By comparison, Mobile’s population has held pretty steady in recent years — fallen, in fact. It begs the question, if a growing population isn’t the cause of the city’s sewage woes, what is?

ABOVE This photo, provided by Mobile Baykeeper, captures a local sewer spill in progress. As explained on Baykeeper’s website, “Spills can be the result of blockages or broken lines, but most often they are the result of aging lines incapable of handling rainfall, ” of which Mobile sees plenty. The watchdog organization has ramped up its efforts against sewage overflow over the past couple years. In September, Baykeeper filed a notice of intent to sue Daphne Utilities over its alleged false reporting of sewage incidents.

“I would say it’s 90 percent aging infrastructure, ” says Paul Kleinschrodt, a project manager at Constantine Engineering. Kleinschrodt, who’s worked in conjunction with MAWSS (Mobile Area Water and Sewer System) to help repair damaged sewer pipes, explains that rainwater entering a faulty pipe is usually responsible for the sewage overflows downstream. During an extreme rain event, rainwater from above and a rising water table from below can inundate the sewer system. Downstream, an overflow is born.

Barbara Shaw, public affairs manager for MAWSS, helps put the issue into perspective. “MAWSS has approximately 3, 200 miles of sanitary sewer line in our service area, ” Shaw says. “Placed end-to-end, that would go from Mobile to Los Angeles and halfway back.” Of the existing pipe, she says, 40 percent is over 50 years old and has reached or exceeded its useful life, and 54 percent is made of vitrified clay. It’s the clay pipes, which easily crack, that allow storm water to infiltrate sewer lines.

MAWSS has several projects planned to reduce sewage overflows, most notably, the construction of a severe weather attenuation basin at Halls Mill Creek and the addition of two 12-million-gallon tanks at Three Mile Creek. “These storage facilities will hold overflows until they can be returned to the sewer line and transported to one of our wastewater treatment facilities, ” Shaw says. “These are stopgap remedies until sewer lines can be replaced or rehabbed, a process that could take decades and hundreds of millions of dollars.” MAWSS is currently at work on a “master plan” to prioritize the projects ahead.

ABOVE “As a researcher, I try to learn what the needs are for the public, municipalities or the agencies and then see where our science can fit to meet those needs. That may mean designing a project to help answer those questions, or it may mean taking a project that we’ve already completed that has relevant data and sharing those data. For a long time, science hasn’t been necessarily encouraged to seek end-users in this way.” – Dr. Ruth Carmichael, Senior Marine Scientist at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab

Photo by Matthew Coughlin

Tracing the Tides

When an overflow does reach our waterways, it’s good to know we have experts looking out for us. On this winter Tuesday morning, Dr. Ruth Carmichael has jury duty. For folks like you and me, this civic responsibility is a mere inconvenience — a slight speed bump in the workweek. But for a senior marine scientist at the Dauphin Island Sea Lab, whose days are spent observing horseshoe crabs and tracking manatees, it might constitute cruel and unusual punishment. Thankfully, Dr. Carmichael is released before lunch and able to make our appointment at the 5 Rivers Delta Center on the Causeway. She seems relieved to be back within a cast-net’s throw of the water.

Dr. Carmichael has worked at the Sea Lab for the past 11 years and is an associate professor of marine sciences at the University of South Alabama. According to her bio on the university’s website, her primary research focuses on “the mechanisms by which anthropogenic-driven perturbations affect coastal habitats and species.” When we meet, she graciously elaborates.

“I look at tracing human influence in coastal systems, ” she says. “So basically, the effects of what people do on land, and how those activities affect food resources and habitats for animals in the water. For the past 20 years or so, a big part of that has been human wastewater.”

For as long as human beings have stood on dry land, we’ve altered it. We’ve plowed fields to grow food, we’ve dug foundations on which to build our homes, we’ve paved our driveways and built our interstates. “And as we do so, ” Dr. Carmichael says, “we change the hydrology of the system.” Rainfall that once filtered naturally through a forest floor now runs across pavement in sheets, testing the capacity of storm drains and picking up contaminants that’ll likely end up in our waterways.

“As we have changed our land-use mosaics, converted from natural pervious surface to impervious surface and put more people on the watershed, we’ve delivered more wastewater to systems, ” she says.

Photo by Kathy Hicks

A couple years ago, a student of Dr. Carmichael’s took sediment cores from the Grand Bay area and, like peering back in time, was able to identify changes in the sediment layers corresponding with the heavy development of the 1960s. As fascinating as it is to look backwards, scientists now have tools that allow for a more immediate recognition and identification of pollutants.

“Elemental analyses allow us to better define specific signatures of different types of wastewater, ” Dr. Carmichael explains. “By doing so, we can identify not only what’s getting in the water, but potentially where it’s coming from.” Some possible wastewater sources could include overboard dumping, failing septic systems or aging municipal infrastructure, among others.

The way forward, she explains, is an acute awareness of the issues we face. “A big push has been made nationally for green buildings, putting in driveways using materials that allow for infiltration of water so it doesn’t just sheet off, supporting upgrades and maintenance of municipal wastewater treatment facilities — so I think there are things that people have become more aware of as far as responsible construction and building. I think the public needs to encourage more municipalities to do that, so that when we plan ahead, we actually plan.”

Yael Girard, executive director of the Weeks Bay Foundation, says the best approach is to conserve the land along our waterways to protect it from future development.

“The Weeks Bay Foundation has been around for nearly 30 years working to conserve critical coastal habitat and educate our community members about the importance of our woods, wetlands, and waterways, ” Girard says. “As an accredited land trust, the Foundation can work with landowners to preserve these unique wild places. In exchange, the landowners are often eligible for considerable tax deductions. This is a win-win for both the environment and our community members.” To date, the Weeks Bay Foundation has protected over 7, 000 acres of wetlands throughout Mobile and Baldwin County.

ABOVE An aerial view near the James M. Barry Electric Generating Plant appears to show wastewater discharge from a coal ash pond into the Mobile River.

On the Horizon

In her Government Street office at Mobile Baykeeper, Executive Director Casi Callaway hardly hesitates when asked to identify the primary threats facing Mobile Bay today: “Sewage and coal ash.”

She’s referring of course to the coal ash pond at the James M. Barry Electric Generating Plant, operated by Alabama Power in north Mobile County. Coal ash, the toxic waste that remains after coal is burned, is a cocktail of unsavory ingredients, including mercury and arsenic. The ash pond at Plant Barry contains more than 16 million tons of coal ash and is bordered on three sides by the Mobile River. For Callaway, the threat of a catastrophic breaching event at the pond is what makes her lose sleep at night. Such a spill wouldn’t be without precedent. A 2008 coal ash spill in Kingston, Tennessee, released more than 6 million tons of coal ash, contaminating rivers and burying homes. Callaway estimates that, based on “back-of-the-napkin calculations, ” the worst-case scenario at Plant Barry could deposit a layer of ash three-feet deep along the Mobile River from the ash pond to the Causeway. Besides the obvious environmental ramifications of such an event, Callaway cites the effect that shutting down the Mobile River could have on industry — potentially millions of dollars a day for some companies.

“The positive is that Alabama Power can fix it really easily, ” Callaway says. “It will take money and be expensive, but not as much as cleaning up a coal ash spill.” While Alabama Power has agreed to “cap” the ash pond with an impermeable lid to seal out any water, Baykeeper would like to see the ash excavated and removed to an upland, lined landfill. The cap, Callaway says, will do nothing to prevent the leaching of dangerous chemicals into the groundwater below.

Callaway notes that Georgia Power, Alabama Power’s brother company under Southern Company, has excavated ash ponds without a fight. “That lays the groundwork for us to demand it in Alabama, ” she says. “Alabama Power is a hero to us over and over again. They’re the ones who turn our power back on after storms, they fund education and countless other things, and they still have the opportunity to be a leader on this issue.”

A spokesperson for Alabama Power maintains that the company’s decision to cap the coal ash pond in place is an adequate measure and one that is in accordance with current EPA regulations.

ABOVE Cade Kistler, program director with Mobile Baykeeper, tests the water quality of Fly Creek following an August sewage spill.

Playing the Hand that’s Dealt

Make no mistake, Mobile Bay is far from dead. Just ask the 300 bird species that migrate through the delta every year, the 350 species of freshwater fish, the alligators and American lotus, the manatees and mussels. And though the scope of the Bay’s problems seems large and imposing, there are success stories out there. Tampa Bay, Dr. Carmichael says, is a wonderful case study for a water body making great strides in the fight for better water quality, as evidenced by their successful seagrass restoration.

“We should be careful not to beat ourselves up too much for past wrongs and recognize the fact that conservation science in general is young, ” Dr. Carmichael says. ““We need to focus on what will move us ahead. We have to now say, ‘These are the cards we have before us. How do we best play them?’”

What you can do today

Report what you see

Any suspicious activities concerning sewage overflow or pollutants of any kind should be reported to city officials and Mobile Baykeeper.

Avoid single-use plastics

Refuse plastic straws at restaurants, take your own shopping bags to the store and pack lunches in a reusable container.

Use a grease container

Help the fight against grease blockages by participating in your city’s grease recycling program.

Become a member of Mobile Baykeeper

Help fund restoration projects, water testing, cleanups and more. Also, call Baykeeper for a “bite-sized” project of your own.

Make calls, send emails and write letters

Make sure local and state officials know where you stand.

Start conversations about these issues

Spread awareness of these issues through word of mouth.