The man at the bus stop narrowed his eyes. It was early, not yet 4:30 a.m., but he could sense somebody was walking toward him up Old Shell Road. Out of the darkness, a figure slowly materialized, and the man found himself staring at a boy, no older than 15, striding along purposefully toward the intersection of Old Shell Road and McGregor Avenue. The boy wore no shoes, and in his hands, he cradled a shotgun.

The mysterious youngster came within several feet of the bus stop, apparently unaware of the man’s presence. The boy, it seemed, was wholly fixated on the intersection’s blinking traffic light, much like the insects swarming in its beam. In those days, before Spring Hill was absorbed by Mobile, that light was the only source of illumination for quite some distance. But the boy was here to fix that.

The boy’s name was Johnny Wilson, and believe it or not, this wasn’t his first clandestine visit to the intersection. In fact, Spring Hill’s first traffic light, installed at this junction in the early 1950s, had been shot out so many times over the previous weeks that the sheriff promised a reward to anyone who could identify the trigger-happy culprits. The average Springhillian knew the guilty parties, but no one ever came forward.

The boy scanned his surroundings, realizing then that he had company. He froze and stared at the man, thinking. After a moment of silence, he nodded toward the light. “You for it or against it?” he asked the man.

“A-Against it!” the man stammered, as if he really had a choice.

Satisfied, Johnny smirked, raised his weapon and fired, and Spring Hill returned to darkness for yet another night.

Identity Crisis

“People don’t realize Spring Hill wasn’t always like it is now, ” says Kit Caffey, who was born in the outlying community in 1927. “It really was sort of wild and woodsy.”

Considering Spring Hill wasn’t incorporated into Mobile until 1956, the community had an identity all its own for most of Kit’s young life. A streetcar rattled past her home on Old Shell, barefooted boys hunted squirrels and rabbits in Wragg Swamp, cattle roamed freely outside the country club. In fact, Kit was a young woman before her house even had a real address.

“Until then, we’d just say we lived on Old Shell Road in Spring Hill, the second house east of College Lane, ” she says with a knowing laugh.

Today, Spring Hill is one of Mobile’s most beloved residential areas, but it hardly resembles its younger, country self. In short, if a teenaged Johnny Wilson were let loose in Spring Hill tomorrow, chances are he’d run out of shotgun shells.

“People felt like that street light was alien to everything they grew up with, ” Ben Wilson, Johnny’s little brother, explains. “And it was just a matter of time before the big city swallowed up their country playground. Everybody was afraid Spring Hill would lose its identity.”

If you pay close attention to the stories of old Spring Hill, you’ll always find a trace of this sentiment — this disdain for the newfangled. For children like Johnny and his peers, beacons of civilization, such as the traffic light, must’ve stuck out like a sore thumb. Time and time again, as society snaked its way up Old Shell Road, the miscreants on the hill pounced. They weren’t making some political statement or organized effort. They were just kids, fighting to keep the world the way they liked it, albeit with a “Lord of the Flies” flare. Behind a grin and mischievous wink, these thick-skinned country kids were gonna fight like hell to keep society at bay.

Rascals on the Hill

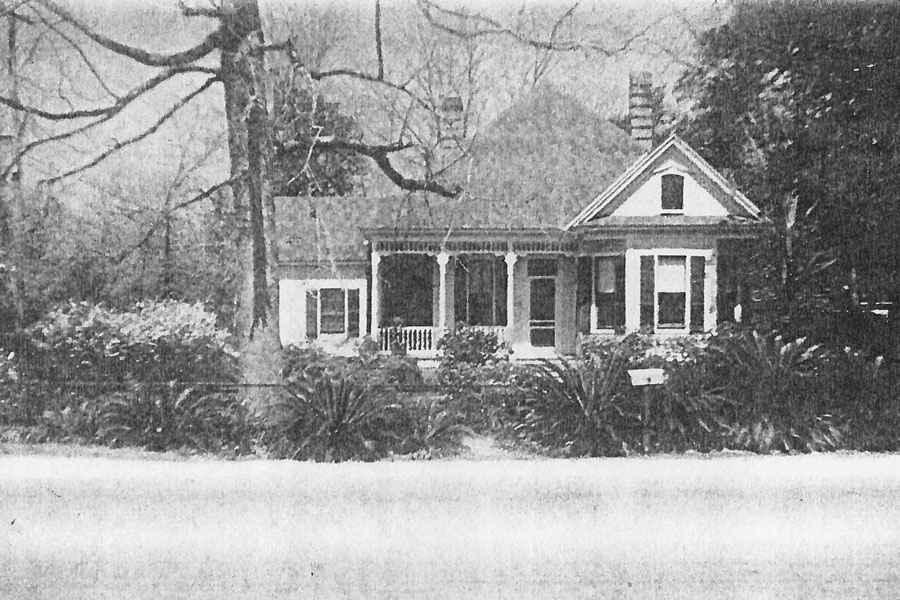

Spring Hill, so named for its abundance of natural springs, has always been considered an idyllic and healthful place. With an elevation of 215 feet, the oak-studded hill was a treasured getaway for 19th century Mobilians, many of whom built vacation homes in the area to escape Mobile’s summer heat and yellow fever epidemics.

Over the years, as summer vacationers gave way to permanent residents, the hilltop community began to formulate its own distinct personality — a sort of wild sophistication. “If it was wild, it was wild with a touch of class, ” says Kit Caffey.

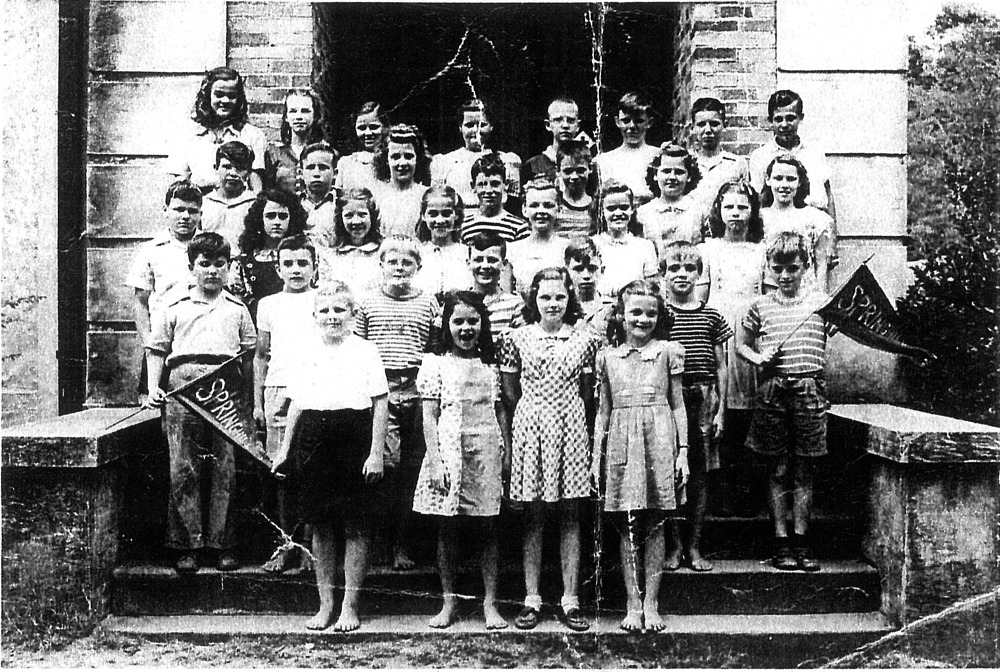

Of course, people have a natural tendency to romanticize their childhoods. Memories grow sweeter with time, and stories are tenderly polished with age. But a quick study of any class photo from Spring Hill School (renamed Mary B. Austin in 1943) attests to the wonderful absurdity of an upbringing on the hill. In the black and white images, spanning several years, a majority of the grinning pupils pose proudly on two dirty, bare feet.

“The rule was, if you came to school barefoot, that was fine, ” explains Ann Wilson Wesley, a former barefooted student. “If you came with shoes on, you kept your shoes on.” The children, of course, were well aware of this rule — and how to manipulate it. One school morning, Ann’s mother found 12 pairs of shoes hidden away beneath her camellia bushes.

Whether it was a rebellion against shoes or a prank on the streetcar, you can bet it was done with style and wit. It takes a clever kid, for example, to realize that a little bit of grease on the streetcar tracks made it impossible for the heavy vehicle to manage the incline. Or that, from a distance, a string tied across Old Shell Road and draped with toilet paper looked a lot like a picket fence had been built across the road overnight.

“My first dog got run over by the streetcar, ” Kit remembers. “But before my time, it was a mule-drawn car, and they would attach oxen to get up the hill.” Every day, the streetcar delivered visitors from the city, elementary school teachers commuting from Mobile and city mothers bringing their children to play in the “country.” On such outings, Mobile kids were usually more supervised than their Spring Hill counterparts.

“Town mothers didn’t understand our freedom, ” Kit says. “They didn’t want their children turned loose in Spring Hill. But we were bad in our own way, ” she says of her peers. “We weren’t bad by today’s standards.”

L.J. Britain, born in 1932, worked as paperboy for the Cedars, a small community within Spring Hill. After delivering his daily batch of 47 newspapers, L.J. and his brothers, Francis and Johnny, had plenty of ways to keep themselves entertained. “We used to sit over on Old Shell Road in somebody’s backyard with .22 rifles and shoot at the water tower and see how long it’d take the bullet to hit the tank, ” L.J. says. “We could hear it clean back on Old Shell Road, that’s how quiet it was. You’d never be able to hear the bullet now.”

At one time, Spring Hill provided all of Mobile’s drinking water, which was pumped from Three Mile Creek into the water tower and reservoir. The Britain boys were known to skinny dip in the reservoir from time to time. That is, until the caretaker and his dogs would chase them off.

“Kids in Spring Hill never let something like a fence stop them, ” Day Gates, another lifelong Springhillian, explains.

Those boys spent a lot of time on their legs, running from trouble across dirt roads or ambling down rocky gullies. The evidence was in the soles of their feet, which were tough enough to extinguish cigarettes they shouldn’t have been smoking in the first place. One story goes that on a winter’s day in Spring Hill, the barber announced to his shop full of customers, “I bet everybody in here that my next customer is gonna be barefooted.” Sure enough, up walked Francis Britain in 20-degree weather, barefooted as a yard dog.

The Pearce brothers on Dilston Lane were another force to be reckoned with, liable to shoot the bluejays in your birdbath or sneak around the country club gigging frogs late at night. Their grandmother, Annie Starkey Pearce Howard, lived in what is now the Carpe Diem coffee house. Originally from Wales, Mrs. Howard added an air of sophistication to Dilston Lane. “Tea, darlings?” she’d ask the neighborhood children.

Of course, such high culture did nothing but put a target on Mrs. Howard’s back; her grandsons Mac, David and Peter convinced her that, in America, greetings are exchanged with an extension of the middle finger.

Mac once brought a small alligator back from Gulf Shores that he kept tied up in the family yard. He and Johnny Britain would put the gator on a short cord in the backseat of Johnny’s truck and pick up Spring Hill College boys thumbing for a beer run. “They’d be sitting three on top of one another in the backseat as that gator hissed at them inches away, ” Mac says.

And of course, directly across from the entrance to Spring Hill College lived the Wilson kids: Ann, Johnny, Becky, and twins Tom and Ben. The Pearce boys took to hanging the young twins by their belts to a telephone pole on Dilston Lane. Whenever the boys managed to get down, much of their time was spent in College Lake (now Mirror Lake), daring one another to slip into “Dead Man’s Coffin, ” the spot where a near-freezing cold spring rolled into the lake.

It was a quieter, simpler time. “You could sit on our porch looking out on Old Shell during the summer, and a car might go past every 20 minutes, ” Tom Wilson says. “And I could count on one hand the number of times we locked our doors.”

After Mobile absorbed Spring Hill in 1956, it didn’t take long for the city folks to find it. “In the 1960s, it became fashionable to live in Spring Hill, ” Tom Wilson explains. Gradually, roads were paved and more traffic lights were installed. Gone were the days of walking down the middle of Old Shell Road or shooting at whatever moved in Wragg Swamp. Some will say it’s for the better, some will say it’s not.

But the next time you drive through the intersection of Old Shell Road and McGregor Avenue, beneath the canopy of traffic lights, put yourself in the shoes of the man at the bus stop — eyes locked with a Springhellion and faced with a simple question. “You for it or against it?”