She didn’t particularly enjoy working at her father’s sawmill. Her first job there, her first job anywhere, was as a summer-time clerk in the commissary store. It was run by a temperamental, threatening man, and she constantly worried that a fistfight would break out.

Around the age of 16, her father taught her how to scale logs, but that wasn’t much of an improvement, the hot temper of the commissary store manager simply replaced by the heat of open-air labor at a sawmill in Jackson, Alabama. The lumber truck would roll in and the young girl would get to work, measuring the trees for volume and grade and paying the driver for their worth.

“I was never really good at it,” Ann Bedsole says, laughing. “I don’t think [my father] ever counted on my scale. I think he had somebody else watching me who knew more about it.”

Today, reminiscing on those humid, dusty summers at M.W. Smith Lumber Co. in the 1940s, Bedsole looks out her office window at an equally hot Bienville Square. The foot traffic, she says, keeps the view interesting.

“The problem is, sometimes you get too interested.”

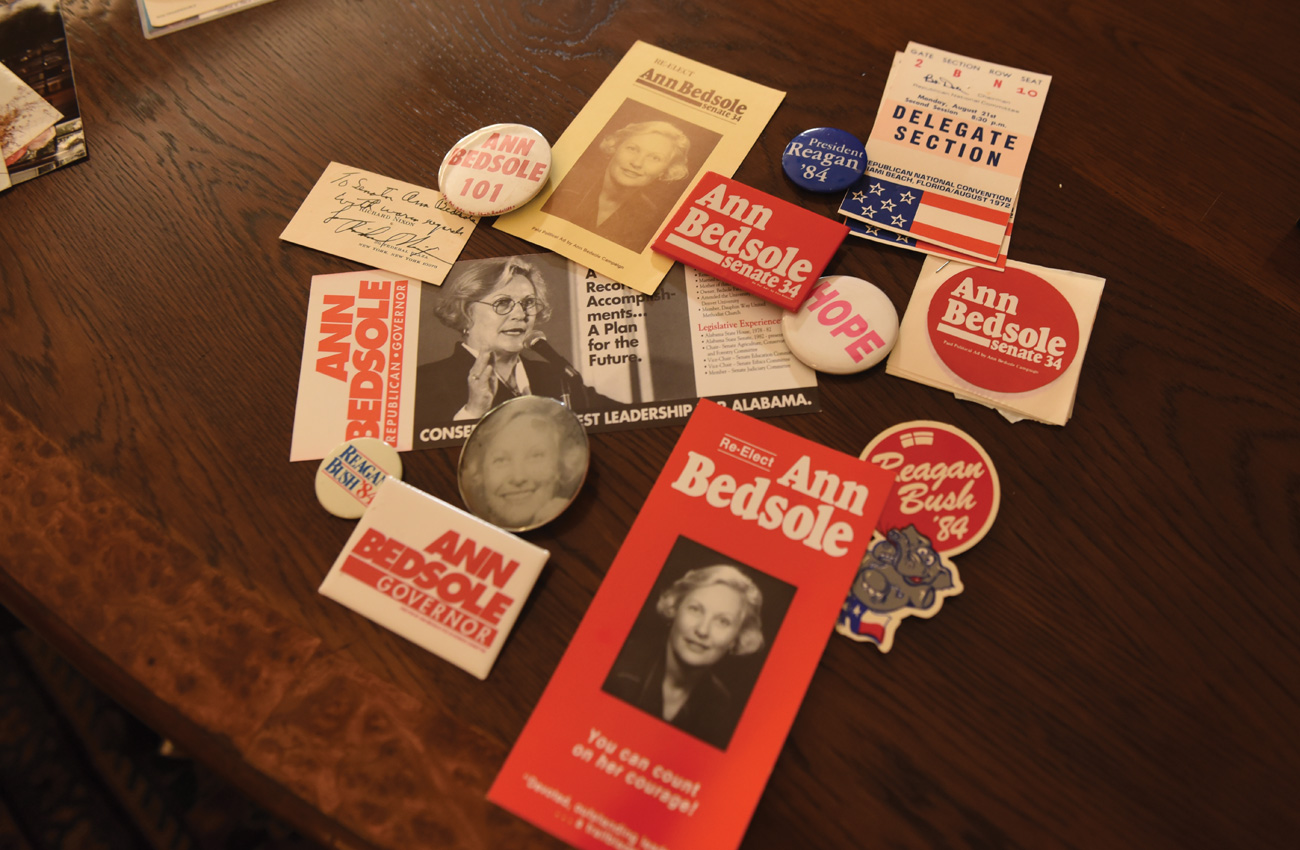

Knowing what we know now — that Bedsole would go on to become the first Republican woman elected to the Alabama House of Representatives, the first woman elected to the state Senate, a founder of the Alabama School of Math and Science, chairman of the Mobile Tricentennial Committee and, today, chairman of the Sybil Smith Foundation — it’s fun to imagine that teenaged Bedsole, clambering over logs at her father’s sawmill, uncertain about her future.

“I always kind of thought I’d just work at the sawmill,” she says. But life, as it often does, had other plans.

To Mobile

Born Margaret Anna Smith in Selma, Alabama, Bedsole’s earliest memory is of playing with the neighborhood children in a shaded cemetery near her home, under the watchful eyes of family nurses perched on the tombstones. When Ann was 5, her father purchased the sawmill, and the family moved to Jackson.

“It was a really good childhood,” Bedsole says. “It was typical of the ‘30s in Alabama. Nobody locked their doors … If you did anything bad, misbehaved, your mama got a call, no matter where you were.”

Surrounded by sandy gullies and acres of loblolly pines, Bedsole and her sister found that the pine straw was thick enough to race their sleds down steep embankments. On the hottest days, the pair could be found at Jackson’s only swimming hole, a natural pool with an anchored platform in the middle.

“It was called the Lawless Pool,” Bedsole says. “Because Mr. Lawless ran it. I always thought that was a funny name.”

Bedsole spent most of her adolescence in Jackson, although she’d finish high school in Waynesboro, Virginia.

“I’ll tell you what, I married when I was 19, and after a while I had two children,” she says. “We married way too young, didn’t know what we were doing, and very quickly decided we would get a divorce.”

She studied for a short time at the University of Alabama and Denver University but found herself back home in Jackson in her late 20s. She was introduced to her future husband Palmer Bedsole who, at the time, was dating her closest friend.

“[My friend] later told people, ‘I really didn’t want Palmer, so I just gave him to Ann,’” Bedsole says with a laugh. In 1958, the married couple moved to Mobile where they quickly immersed themselves into the fabric of the city.

To Montgomery

Ann Bedsole was fed up. After years of serving as the Republican chairman of Mobile’s Ward 4 (before the district system) and watching a series of failed Republican campaigns, she’d had enough.

In 1978, Democrat Sonny Callahan was elected to the Alabama Senate, leaving a vacant seat in the Alabama House of Representatives. Armed with a handbook by Don Siegelman on how to run a campaign, Bedsole launched her political career.

“The most fun was the House campaign,” she says. “We were doing the best we could, not knowing anything other than what Siegelman wrote.”

Upon becoming the first Republican woman elected to the state House, Bedsole eagerly reported to Montgomery. During her tenure in the House, she played a vital role in the passage of several bills, one to introduce public kindergarten, another to improve a widow’s chances of inheriting her husband’s property if he died without a will. The experience, she says, was rewarding but frustrating.

“I really didn’t like being in the House. It’s really difficult to get anything done,” Bedsole says. She recalls the time a fellow female representative backtracked on her promise to vote for a bill Bedsole supported. The woman explained that a male colleague had convinced her otherwise. “He’s just so good looking,” the woman sighed.

Remembering this conversation 40 years later, Bedsole slaps a palm on her desk. “I was ready to leave for the Senate right then,” she says. “I just thought, ‘Not even the women can stick together in here.’”

After one term in the House, Bedsole opted to run for the state Senate in 1982, again filling a vacancy left by Callahan. Bedsole remembers a T-shirt a 70-year-old Mobilian gave her around that time, which read, “A woman’s place is in the House — and Senate.”

The night of her victory, a reporter asked Bedsole what it was like to be Alabama’s first female state senator. She gently corrected him. Sybil Poole, she said, held that distinction. No, he responded, Poole had served as secretary of state.

“I had no idea,” Bedsole says. “You know, we should have done our homework and looked it up! But it wasn’t important to be a woman. The important thing was to be in the Senate. That’s why I didn’t realize it, because it didn’t really matter.”

To some, however, it mattered a great deal. On Bedsole’s first day in the Senate, departing Lt. Governor George McMillan took the opportunity to address the chamber.

“You have a woman in here now, and you have to accept the way life is today,” Bedsole says, remembering McMillan’s words. “Be nice to her, treat her like you do everybody else.

“I really appreciated that tremendously,” she says. “But it didn’t do a damn bit of good.” During that first year, Bedsole says, “I couldn’t even get anybody [in the Senate] to go to lunch with me.” Instead, she dined with secretaries or with old friends from the House.

But over her three terms in the Senate, Bedsole bore witness to a major change in attitude, toward women and toward Republicans. During her time in the legislature, she played an instrumental role in the creation of the Alabama School of Math and Science (ASMS) and chaired the Agriculture, Conservation and Forestry Committee.

In 1994, rather than seeking a fourth Senate term, Bedsole entered the race for governor. “I think I ran a really bad campaign. I did not stick to Siegelman’s handbook.”

Feeling confident of her chances in the Republican primary, Bedsole says she prematurely directed her campaign towards the general public. In a runoff election, she lost the Republican primary to the eventual governor, Fob James.

“It just broke my heart,” she says.

A Footprint

In 2007, Rep. Jo Bonner stood on the floor of the U.S. House of Representatives, inspired by the recent dedication of the Ann Smith Bedsole Library at ASMS.

“To say [Bedsole] has been a political pioneer, as well as personal inspiration to many of us, would be a considerable understatement,” Bonner said. “Madam Speaker, Ann Bedsole has spent practically her entire adult life giving to others, and I ask my colleagues to join with me in thanking her for her commitment to so many wonderful missions.”

It’s easy to wonder what has inspired her life of achievement and service — president of the ASMS Foundation Board of Directors, trustee of Spring Hill College and Huntingdon College, founder of Mobile Historic Homes Tours, Mobilian of the Year, Philanthropist of the Year, three honorary doctorates, induction into the Alabama Academy of Honor and current chairman of the Sybil Smith Foundation, named after her mother. These days, most of Bedsole’s time and energy are focused on establishing an endowment fund for the Sybil Smith Family Village, a transitional housing program and facility at the Dumas Wesley Community Center for homeless women with children.

“I think it’s my father. He always said, ‘Don’t go through this life and not leave something. Don’t forget to leave your footprint.’”

Bedsole’s footprint is large: three children, seven grandchildren, one great-grandchild and a legacy that will reverberate for generations of Alabamians.

“Mobilians don’t need to remember my name,” she says. “Just take care of these things I’m leaving here.”