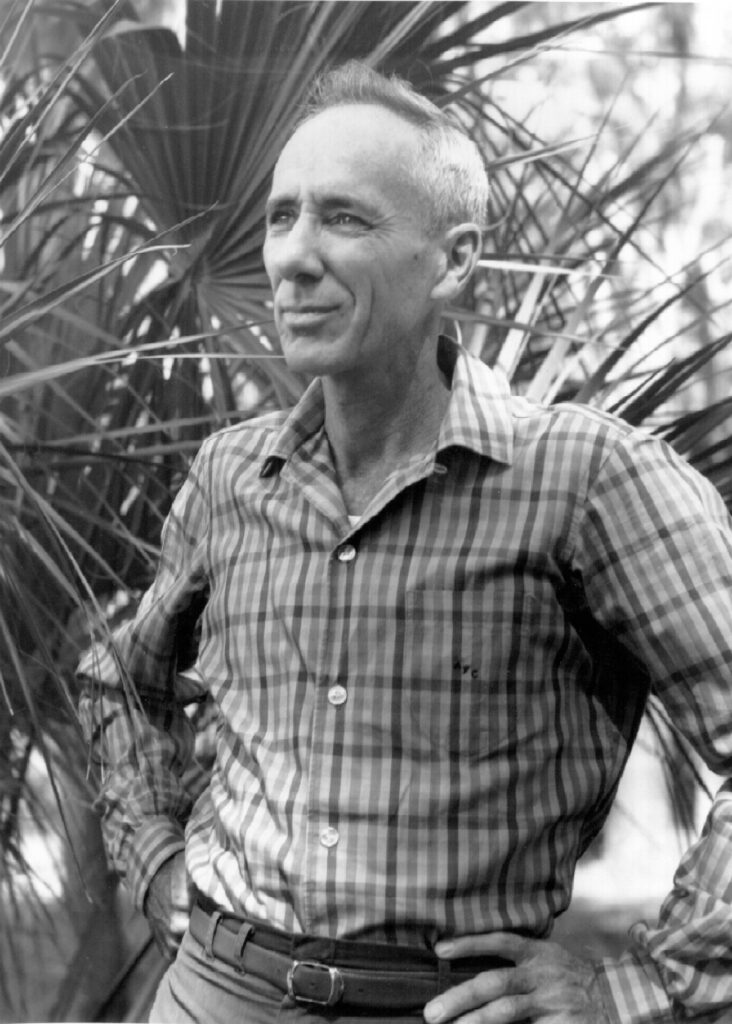

World-renowned naturalist Archie Carr was born in Mobile in 1909. His dad’s name is still engraved on the plaque of ministers down in the old Presbyterian church on Government Street. As a boy, Carr rode his bike to the Delta to spend his days fishing and exploring. As an adult, he was instrumental in saving sea turtles from extinction. Although Carr spent his career at the University of Florida, those youthful days running free around the Mobile-Tensaw Delta, one of the last undammed, free-flowing deltas left on this planet, colored the rest of his life and work.

Carr loved the outdoors. He loved anything and everything that nature had to offer; as such, he knew nearly as much about the spawning habits of the Suwanee River sturgeon, the life cycle of carnivorous plants along the Panhandle, Spanish moss forests and the epithetic bromeliads of the Everglades as he did about topics within his more narrowly defined academic purview. According to Bob Graham, Florida’s one-time governor and U.S. senator, Carr was beyond just a scientist; he understood the singularity of Florida’s landscape. Peter Matthiessen, a New York Times best-selling author best known for his novel “Killing Mister Watson,” once called Carr an “old-fashioned generalist.” Although the term generalist is no longer in vogue in the sciences, it does describe the depth of Carr’s knowledge and the breadth of his interests — the pillars and foundation of his success.

Many would consider Carr a colorful character. Working as a professor in Gainesville, he chose to live on a farm deep in the heart of Paynes Prairie. His backyard crawled with colorful creatures that most people would consider downright frightening. Carr and his wife Marjorie, a well-known biologist and naturalist in her own right, raised five children on the prairie — a place only naturalists could love. In fact, Marjorie liked to joke that they reared and educated five children on their small farm, “and no one died.”

Carr relished taking his students into the field. He preached that the natural world does not live in a book or on a specimen slide, and thus proper zoologists need to get their hands dirty. Still, walking around in the mud and muck or rolling up water hyacinth didn’t appeal to every young scholar. Not knowing what was in the hyacinth was a bit disconcerting to some. And a few of his students paid the price when bitten by what locals call the hot bug — a minor bug with a caustic attitude. According to Carr, “The bite of the hot bug is no worse than the sting of a bee.” But the hot bug’s bite was so painful that, on more than one occasion, a less-than-motivated would-be zoologist changed majors. Muck itch had the same effect. It burned on contact and left one with a lingering rash, but the irritation and burning sensation only lasted for a few days. Both were inevitable.

Unfortunately, Carr also witnessed the world he loved driven to the brink of extinction. He was forced to watch helplessly as timber companies greedily harvested the hammocks of the Everglades for exotic hardwoods, such as West Indian mahogany, live oak, gumbo-limbo, black iron and sweet bay magnolias, without concern for regrowth or the fauna that called them home. Carr had a front-row seat as the Everglades were reduced from 8 million acres across seven counties to a mere 1.1 million acres.

But unlike other ecologists of his time, such as John Kunkel Small and Thomas Barbour, who were alarmed by the same trends, Carr remained upbeat in his message and always did his best to take the high road. One of the aspects that made Carr such an effective conservationist was his ability to focus his message on the positive — on what can still be done — and make science accessible to all. Graham once called Carr a “master teacher and storyteller.” I, for example, had never heard of Carr until Ann Bruce, the librarian at Tallahassee’s Tall Timbers Research Station, gave me a copy of his book “A Naturalist in Florida: A Celebration of Eden.” I fell in love with stories such as “The Bird and the Behemoth,” “All the Way Down Upon the Suwannee River,” “The Moss Forest” and many more. Carr had the unique ability to turn science into something laymen would enjoy reading. He made his subject matter come alive.

Carr once opined, “For most of the wild things on earth, the future must depend on the conscience of mankind.” He knew it would require more than just a village to save what natural treasures were left. There had to be an “all hands on deck” approach, not simply efforts from a few scientists. It would require a paradigm shift in how others think about the natural world. To preserve what’s left of Carr’s vision, mankind would eventually have to protect the remaining flora and fauna for the planet’s sake and not necessarily what’s best for humans.

Years before landing on the doorstep of the University of Florida, Carr fell in love with turtles as a teenager living in Savannah, Georgia. He dedicated his life to saving the ecosystems and habitats crucial for the reproduction of the green sea turtle, the Kemp’s ridley and other sea turtles. He managed to put together a coalition of committed activists, such as Joshua B. Powers, a prominent member of the Inter American Press Association and founder of The Brotherhood of the Green Turtle. Powers founded the Sea Turtle Conservancy in 1959 in response to Carr’s book “The Windward Road,” which first alerted the world to the plight of the sea turtles. Together, and with the help of the Costa Rican government, they put together an even broader coalition when the U.S. Navy offered to provide more resources.

In the end, it took more than 20 years to see any positive results. It turns out, for example, that sea turtles don’t reach reproductive maturity a few years after birth, as Carr and his team had assumed. Rather, it takes decades, a startling and, frankly, inconvenient discovery for scientists. The critical message for those passionate about conservation is that perseverance is an essential virtue in this pursuit. Endurance is key as well. Carr’s determination carried him from Georgia’s Okefenokee Swamp to the rain forest of Honduras, and it all paid off in the end. Thanks to Carr and all the scientists and volunteers who worked diligently through the years, we have finally turned the corner; turtles are now spawning again on beaches worldwide.

By the end of his career as a professor, naturalist, and zoologist at the University of Florida, Carr had published 11 books and more than 120 scientific papers on sea turtles and their habitats. But, what’s more, his ultimate success in preserving sea turtles reminds us that it is worth fighting for conservation and environmental goals, even when it feels like tilting at windmills much of the time.

In 1987, Carr was laid to rest at his home on Wewa Pond near Micanopy, Florida. He was 77 years old. His legacy lives on with each new generation of sea turtles taking to the sea for the first time and with many new generations of naturalists helping us appreciate and protect the diversity of our oceans, deltas and estuaries.

A 4th-century Chinese poet, Chuang-tzu, once wrote, “Good fortune is as light as a feather, and few are strong enough to carry it.” Essentially, success is fleeting, and the strong have to be vigilant. If not, everything we have fought for will disappear.

James Stenson writes about fly-fishing, surfing and culture, and he is the founder of Sweet Waters Adventure, an international adventure travel company catering to fly fishermen and wing shooters, based in Mobile.