In pre-Civil War Mobile, cotton was king, and the very life blood of the city’s economy. It made many Mobilians wealthy, and in one way or another, everyone seemed to be involved in it: merchants, cotton factors, bankers, insurance agents, stevedores, roustabouts, planters, enslaved people and, of course, the captains and pilots of a multitude of steamboats.

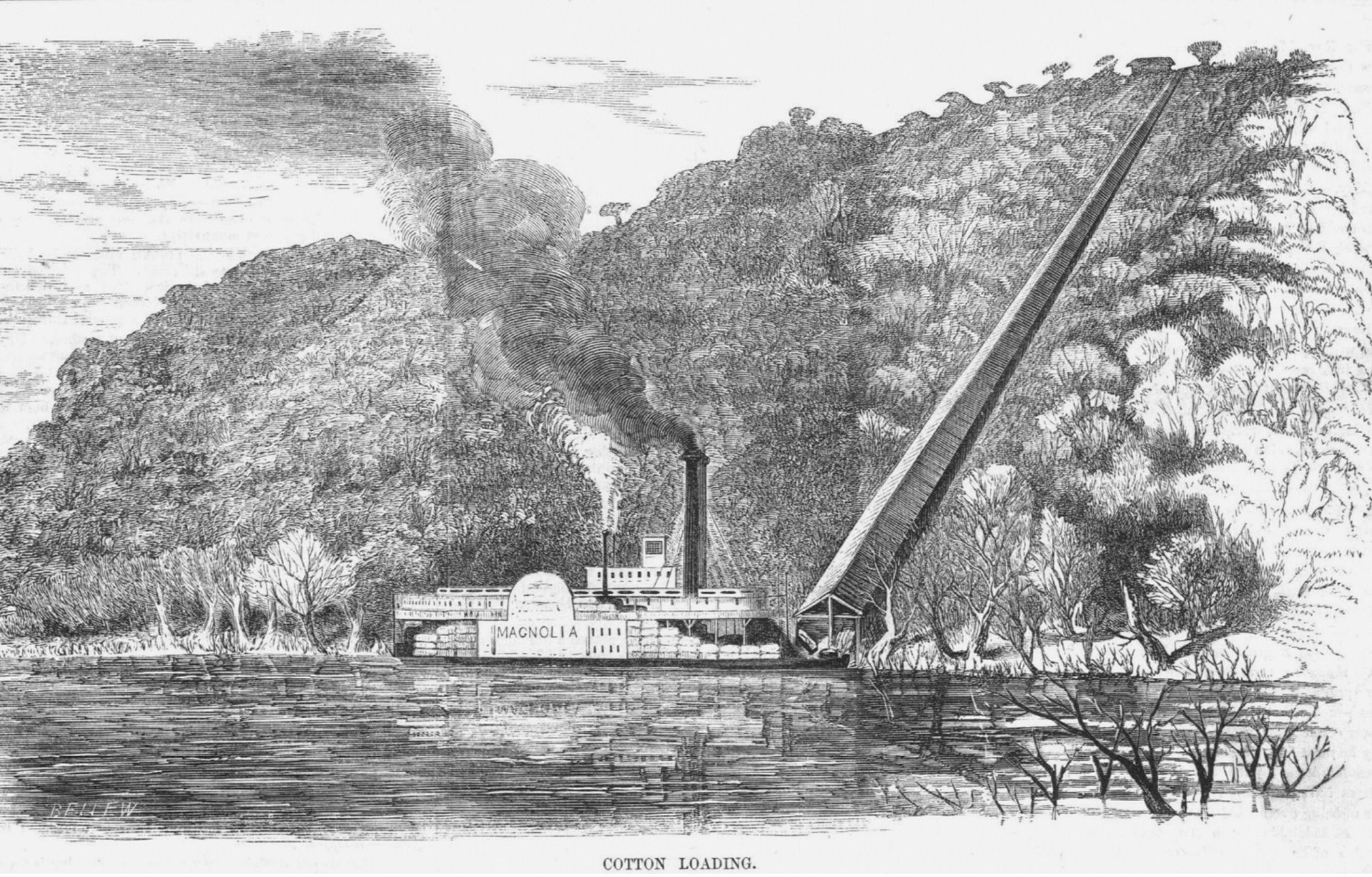

Driven by huge side wheelers, the steamboats were the manmade nautical contributors to the Port City’s cotton economy. They moved hundreds of thousands of cotton bales from the plantations in the Black Belt and hinterlands over the Alabama and Tombigbee Rivers, into the Mobile River and finally the Port of Mobile. From there, it was shipped by ocean-going vessels to New York or Europe.

In 1840, Eli H. Lide noted that “about 40 steamboats were plying up and down” the rivers, the larger ones carrying “3,000 bags of cotton.” As the demand for cotton grew, so did the fleet of steamboats which soon numbered over 50. All along Mobile’s riverfront, dozens of wharfs and warehouses sprang up, accommodating the unloading, compressing and storage of cotton. By 1860, Mobile was America’s third busiest port, trailing only New York and New Orleans.

Clearly, steamboat transportation flourished during this time. Prior to the development of an adequate railway system, it was the most efficient way to move cotton down river, imported goods upriver and, by far, the most comfortable conveyance when traveling to and from Mobile and the state’s inland towns. Yet, early steamboats were hardly appealing to the eye. In fact, some were little more than steam-driven barges.

However, after 1820, they became larger and more attractive, typically about 200 feet in length and 30 feet wide. There were several decks. The main deck, mostly an open area, provided space for stacks of cotton bales and cords of fat pine that fed the furnaces. There were only a few cabins on the main deck which housed the kitchen, the firebox, engine and the boilers. Second-class passengers, along with the deckhands, laborers and Blacks — both enslaved and free — were consigned to this deck and slept wherever they could find a spot among the cotton bales and firewood.

The more affluent passengers found better accommodations on the second deck, featuring a long saloon or lounge running down the center of the vessel. Furnished sleeping cabins lined each side of the saloon, which served as a dining hall for passengers, and was furnished with card tables, rocking chairs and sofas. There, under high windows, passengers could read, relax and gamble. Typically, a great deal of chewing and spitting tobacco took place, which some of the more sophisticated travelers found “very disgusting.” Each of the sleeping cabins had doors opening to the saloon on one side, and onto a gallery or promenade on the outside where passengers leisurely strolled and admired the scenes along the river. Above the second deck was the hurricane deck with cabins for the officers of the boat. Finally, high atop this was a shorter deck and the wheel house where the pilot or captain steered the boat with a commanding view of the river. It was flanked by a pair of tall, iron smokestacks, constantly belching huge clouds of black smoke.

To this day, travel on the steamboats recalls romantic images of the floating palaces of the Old South. But as Harvey Jackson rightly points out in his book, “Rivers of History,” “There are those who thoughtlessly cling to the dream of these glory days with the same rose-tinted tenacity as they hold to the illusion of an Old South…” While that image may seem charming, it’s mostly myth. Steamboats, after all, were primarily designed to carry cotton, and passenger comfort was usually a secondary priority.

In reality, some passengers found traveling by steamboat disagreeable for a number of reasons. There were frequent stops at towns and cotton landings along the way, making for a longer trip than by stage or even horseback. What’s more, the manifest of passengers brought a variety of people from all different backgrounds in close contact with one another. They ranged from frontier Alabamians whose manners and conduct proved coarse and rude to the more cosmopolitan Europeans and Northerners, who found the former “exceedingly offensive both in habits and deportment.”

A case in point involved James Silk Buckingham, a haughty Englishman, who was traveling aboard the steamboat, Medora, in 1839. During the trip, he met another first-class passenger, a cotton planter about 70 years old. Being told the man was worth $100,000, Buckingham was startled. This was indeed a paradox he could not reconcile. Here was an ill-mannered, poorly-dressed man, with a mouthful of tobacco, one eye and only a few teeth, with long, white hair hanging down his back. Buckingham questioned such a contradiction as inconceivable. The answer, of course, was cotton. The man had apparently spent his life driving his slaves, carving out a plantation in the canebrake of the Black Belt, and had accumulated a vast amount of wealth despite lacking anything else which might impress the refined Englishman.

Beyond the social conduct of the passengers, there were other problems of a dangerous nature. Steamboats frequently had accidents, hitting sandbars, submerged logs and snags, leaving the vessels grounded or damaged. However, the most feared disasters were exploding boilers, which could destroy and sink a vessel. When a boiler explosion occurred, passengers and crew were sometimes blown to bits, drowned or horribly scalded by the steams. In 1836, the boilers on the steamboat Ben Franklin burst apart as it left the wharf in Mobile for its routine trip to Montgomery. The blast shook the city, and left the decks scattered with “motionless and mutilated corpses.” Furthermore, fires started from flying engine sparks created calamities when they set the cotton bales ablaze, turning the boat into a floating inferno. The most dramatic tragedy of fire on a steamboat came March 1, 1858, the day the Eliza Battle caught fire from the flaming embers of a passing steamer while on the Tombigbee River. Many of the passengers, trying to escape the flames, jumped overboard into the frigid water and froze to death. Of the 60 passengers onboard, 36 lost their lives.

Despite the dangers surrounding these steamboats, there were occasions which thrilled the passengers as well as crowds of onlookers on the river front. That, of course, was the excitement of the steamboat race. People loved to watch them race. The races were sometimes planned in advance with a lot of hype and betting on the outcome. And, at times, they were spontaneous when one vessel tried to pass another somewhere on the river, triggering a captain’s impulse to race. But they usually began at the wharves of Mobile and raced to the mouth of the river. Rarely were they planned for longer distances, such as Mobile to Demopolis or Montgomery.

The boats had memorable names like Southern Republic, New World, Eliza Battle, Cuba, Ambassador, Beulah, Czar, Maggie F. Burke, James Hewitt and William Jones, Jr. As time passed, they increased in number and size, further romanticizing river life in the South. The best of them were huge and impressive, trimmed in colorful paints and admired as ornate “floating palaces.” As time went on, the captains and pilots of these boats became legends for the adventurous lives they led plying the rivers. Most of them had grown up around the waterfront in Mobile or New Orleans, performing various maritime jobs. They were rough-hewn men, smart, witty, intolerant of an insult or affront, who loved to fight and knew every bend and turn on the inland rivers.

Captains like Bill Meaher, Owen Finnegan, Jesse Cox, George Cloudis and Robert Otis were among the most renowned men ruling the decks of the great steamboats. Robert Otis was by far the most pugnacious and well-known of them. He was in command of the Cuba, which a newspaper boasted was “the most noted racer that ever backed out of our gulf port.” Otis was a small, quiet man with few friends and was described as “a little fighting machine.” His temper had a short fuse, and violence seemed to follow him. Discerning an insult from a certain Captain Allen on the Dauphin Street wharf, Otis quickly proceeded to thrash the man with his fists. Even his own pilot, a man named Pearce, known as a fighter of “powerful physique” had to seek a surgeon’s care after Otis gave him a bloody beating. But the most serious episode in Otis’s combative life occurred when he shot Walter Tuggle, the pilot of a rival boat, whom Otis felt was crowding and endangering his vessel.

Of course, most of the boat captains were not as bellicose as Captain Otis, who somehow escaped serving jail time for the shooting incident. Nevertheless, they were all hard, competitive men, who steered their crafts through the dangerous and exciting era of the steamboats. Like the invincible boats they commanded, all of them gradually vanished. Those captains were Lords of the rivers for a time, and the boats they ruled like mythological dragons, breathing smoke and fire. The steamboats continued to ply Alabama’s rivers for decades after the Civil War until they were eventually replaced with tugboats pushing barges, and faster passenger and freight trains. Yet the tales of traveling on the steamboats and the legends of the captains still remain a romanticized memory of early Mobile.

Russell W. Blount Jr. is the author of five books on the American Civil War as well as a number of articles on 19th-century America in historical journals and publications.