In the autumn of 1558, a small Spanish squadron hove into Mobile Bay and furled its stained sails. During the following days, lightly armed soldiers and barefooted sailors explored the environs in small boats and afoot. Their commander liked the place, and after returning to Veracruz, New Spain (modern Mexico), he sat down with a scribe and witnesses to provide a report, or “declaration” as it was called, to the viceroy. The commander’s account was sworn to, signed and sent up the chain of command. Thereafter, it was archived and forgotten.

Almost three centuries later, during the 1850s, the American lawyer, diplomat and historian Thomas Buckingham Smith stumbled upon it in a Spanish library and made a copy for his files. After Smith’s death, a researcher named Herbert Ingram Priestly found the document and included it in his monumental two-volume study, “The Luna Papers, 1559-1561” (1928). The University of Alabama Press reprinted these two books in 2010 as a single volume, but despite that, the declaration remains obscure to all but a few specialists. This is unfortunate, because it represents one of the oldest and most detailed descriptions of Mobile Bay on record and deserves wider circulation.

The 1558 voyage was launched to scout a suitable landing site for Tristán de Arellano y Luna’s large colonization fleet. Luna’s goal was to establish a Spanish presence on the northern Gulf, and then to reach the Atlantic and build a fort to protect vital trade routes. Despite earlier entradas like those of Panfilo de Narváez and Hernando de Soto, the Spanish were woefully ignorant of the northern Gulf littoral, and Luna needed accurate information to avoid unknown perils.

Enter Don Guido de Lavazares, a Seville native who moved to New Spain around 1530. He was a capable seaman and businessman “of great prudence and noble intention,” in the words of one 19th-century historian. Given this competence, the viceroy ordered Lavazares to reconnoiter from Veracruz all the way to the Florida Keys, better than 2,000 miles, and hurry back. Three ships were provided — a bark, a lateen rigged sloop and a shallop — frighteningly small by modern standards but well-built, fast and seaworthy. Sixty sailors and soldiers were attached to this tiny fleet. They included skilled pilots like Bernaldo Peloso and Rodrigo Ranjel, Soto veterans who owned at least some familiarity with the intended destination; and a sun-bronzed mix of carpenters, caulkers, sail menders, helms- men, seamen and fighting men with deadly Toledo steel rapiers.

Lavazares’s flotilla departed on September 3 and within a few days was coasting the Texas shore. Several bays and inlets were probed but proved too shallow. The ships sailed further east and threaded the Chandeleur Islands and then approached the Mississippi River’s muddy mouth. Lavazares found the marshy country there “all subject to overflow” and unsuited to settlement.

Farther eastward the fleet sighted an island (Dauphin) and a long peninsula backed by a large sheet of water. This looked promising, and one by one the ships tacked into the expansive bay and dropped anchor, blessed relief to the men after relentless off- shore tossing.

“This was the largest and most commodious bay … found in that region for the pur- pose which his Majesty orders,” Lavazares reported. He duly named it Bahia Filipina in honor of Spain’s King Phillip II.

Securely positioned inside the bar, the Spaniards ranged both sides of the bay and even reached the delta’s muddy margins.

“The country to the east of the bay is higher than that on the west side,” Lavazares’s report continued. It detailed “red bro- ken lands … where bricks can be made” (Montrose), and “yellow and grayish clay” on the western side perfect for making “jars and other things.”

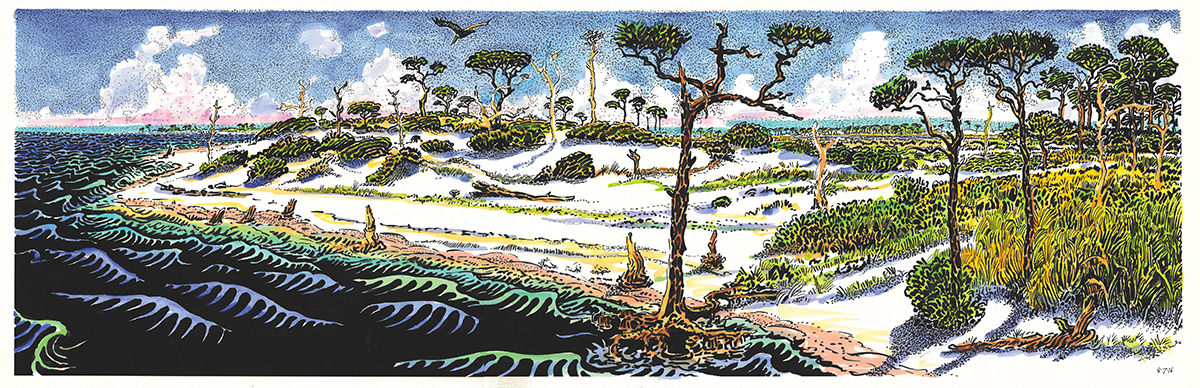

Resources were everywhere. “In the bay and its vicinity are many fish and shell- fish; there are many pine trees suitable for making masts and yards; there are oaks, nut trees, cedars, junipers, laurels, and certain small trees which bear a fruit like chestnuts. All this forest from which ships can be made begins at the water’s edge and runs inland. There are many palmettos and grapevines.”

The awestruck men wandered beneath soaring longleaf pines, marveling at the lack of undergrowth. It was perfect cavalry country where riders could freely gallop brandishing lance and sword. Others thirstily ladled fresh water out of the “copious” Mobile River, while birds of seemingly every variety wheeled overhead. The woods were populated by deer, bear, fox and possum, and copper-skinned Indians scooted across streams in dugout canoes checking their fish traps. Cultivated corn, beans, pumpkins and squash ringed villages where thin columns of blue smoke drifted skyward, children played and women tended to domestic chores.

Satisfied by his reconnaissance, Lavazares ordered the fleet to set sail. Unfortunately, further progress was blocked when the ships were buffeted by contrary Gulf winds. With winter looming, Lavazares deemed it prudent to return to Veracruz. There, he personally emphasized Bahia Filipina’s advantages to both the viceroy and Luna.

But Luna found Filipina unsatisfactory during his 1559 voyage and relocated to deeper Pensacola Bay instead. A strong hurricane wrecked the fleet shortly thereafter, dooming the colonization effort before it had properly begun. What Lavazares thought of Luna’s fateful decision is unknown, but half a millennium on, his assessment of Mobile Bay’s charms certainly rings true to those who call it home today.