Taphophilia. Although a mouthful, the word, rooted in Greek, simply means “love of cemeteries.” While death and love seem like an odd pairing, many people are, in fact, drawn to faded tombstones, ivy-covered mausolea, and weeping statues and willows. But what is it about these buried cities people find so fascinating? The answers, seldom macabre, are as varied as the cemeteries themselves. Some simply find peace amidst park-like landscapes. Others satiate their inquisitive side, poring over nearly-illegible stones, all snapshots of a particular time in history.

Whether you’re a self-proclaimed taphophile, a casual tombstone tourist or an avid folklorist, the following are just a few of the Bay area’s final resting places. And if you listen closely, you may even hear a tale or two.

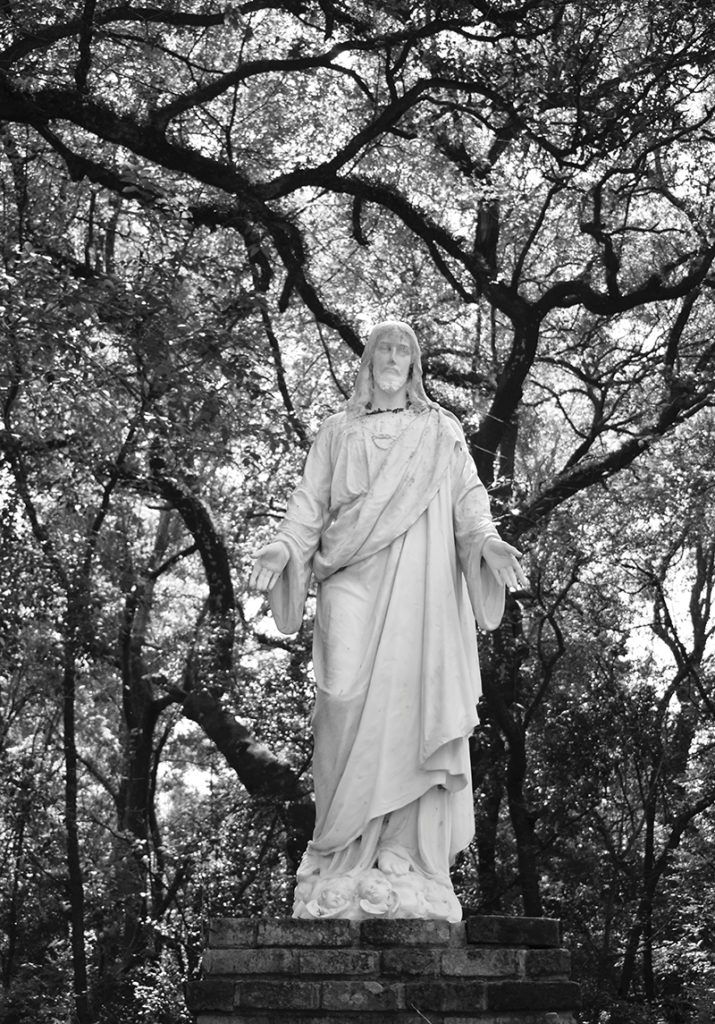

Magnolia Cemetery | Mobile, est. 1836

Originally called “New Burial Ground,” Magnolia is Mobile’s second-oldest and largest cemetery, with over 100,000 buried underneath its ancient oaks, green lawns, ornate statuary and crosses. Not all interred in the 120-acre necropolis are documented, as hasty mass burials of men, women and children were common during yellow fever outbreaks. Of those noted, however, are Apache warriors, two Alabama governors, seven congressmen, 20 mayors, six generals, rabbis, free Blacks, society women and physicians such as Josiah Clark Nott. Nott was a founder of the state’s first medical school and one of the first physicians to link mosquitoes to yellow fever, the illness that would sadly claim four of his children, all within one week in 1853. A decade later, two additional Nott children succumbed to disease and war. Sadness still permeates the Nott family plot, which is guarded by a cast-iron Irish Setter.

Although many 19th-century tombs reflect rampant illness, many more mirror Mobile’s then-society by way of fraternal and professional organization plots: Woodmen of the World, Coal Handlers Union, Homeless Seamen and Colored Benevolent Institution Number One. Having burial rights within an organization was a great benefit for skilled laborers, especially during a time of crude insurance practices.

Notable Interments: Walter D. and Bessie Morse Bellingrath, founders of Bellingrath Gardens and Home; Michael Krafft, founder of the Cowbellian de Rakin mystic society; Augusta Evans Wilson, Civil War-era author; John LeFlore, civil rights leader.

Possible Haunt: Legend has it that when attempts are made to move the cast-iron statue known as the “Goddess of Magnolia,” storms are summoned.

Did You Know? Just to the southwest of the cemetery, where the 1940s baseball stadium Hartwell Field once stood, there are nearly 4,000 scattered unmarked graves. The graves are most likely African-American burials from the mid-to-late 19th century.

Sha’arai Shomayim Cemetery | Mobile, est. 1876

When the Jewish Rest section of Magnolia Cemetery reached capacity, Congregation Sha’arai Shomayim established this 15-acre resting land, girded by live oaks and an ornamental cast-iron fence, across the street. Hebrew text adorns the arched gate entrance, as well as many headstones. The Ark of the Covenant and Middle Eastern designs decorate elaborate markers and mausolea, one of the most notable of which is the Eichold-Haas-Brown mausoleum.

Notable Interment: Esau Frohlichstein, one of 14 American soldiers killed during the U.S. siege of Veracruz during the Mexican Revolution. His marker is inscribed with a letter he wrote to his parents the night before his death. It reads, in part, “Don’t be afraid if I get killed.”

Old Plateau Cemetery | Africatown, est. 1874

Resting atop a small hill, just north of downtown Mobile, is Old Plateau Cemetery, also known as Africatown Graveyard. In 1860, the last known group of Africans were brought to America on the slave ship Clotilda. Five years later, the slaves were emancipated. Upon finding it impossible to return to Africa, the group established their own independent society, modeled after their homeland. Old Plateau Cemetery is their final resting place.

The oldest graves are located in the northern portion of the graveyard. Some are designated with engraved headstones; others feature scrawled writings by hand. Curiously, some stones include a drawn hand and upside-down heart. While the meaning of the hand is uncertain, some speculate it represents the hand of God reaching down or the hand of the deceased reaching out for something left behind. The meaning of the upside-down heart, however, can be traced back to Ghana, Africa, the region from where the Clotilda passengers came. The African word “Sankofa,” represented by an upended heart, loosely means “go back and fetch it.” Whether it is a directive meant for the deceased or the deceased’s loved ones is unclear.

In 2010, an archaeologist located hundreds of previously unmarked graves by using ground-penetrating radar, bringing the cemetery total close to 3,000. Hundreds more may still be underfoot in a nearby wooded area.

Notable Interments: Cudjoe Lewis, the last known Clotilda survivor; Emperor Green, a Buffalo Soldier, one of many Black American soldiers recruited to fight on the Western frontier.

Did You Know? It is not uncommon to find conch shells placed around African graves. Slave ships en route to America often stopped in the Caribbean, and while in the islands, passengers were allowed to feast on mollusk, such as queen conch, in an effort to restore their health.

Saluda Hill Cemetery | Spanish Fort, est. 1824

Down Highway 225, across the road from Historic Blakeley State Park, is a small, piney grove named Saluda Hill Cemetery. The gated entrance is flanked by brick columns and an historical marker, reading in part, “Among the graves here is that of Zachariah Godbold, the only known Revolutionary War veteran buried in Baldwin County.”

Among others interred here are the first settlers of Blakeley, a long-abandoned French colonial plantation and the first non-Indian settlement in the area.

During the early 1820s, Blakeley’s population exceeded Mobile’s, due in part to its easily accessible port on the Tensaw River. Yellow fever caused numbers to dwindle quickly, however, and after the Civil War, Blakeley became a ghost town.

Explore More: Early Blakeley residents are also thought to be buried in unmarked graves across the street in Blakeley Cemetery (established circa 1814), just inside the state park entrance.

Catholic Cemetery | Mobile, est. 1848

Michael Portier, the first Roman Catholic Bishop of Mobile, established the 150-acre burial ground, formerly known as Stone Street Cemetery. Like Magnolia’s plots for professional groups, Catholic Cemetery includes plots for religious orders, including Brothers of the Sacred Heart, Daughters of Charity, Little Sisters of the Poor and Sisters of Mercy.

The cemetery has three distinct sections, the oldest of which, designed by Portier, is laid out in three concentric circles. The reason behind the highly unusual design is unknown, but John S. Sledge, architectural historian for the Mobile Historic Development Commission, speculates in his book “Cities of Silence: A Guide to Mobile’s Historic Cemeteries,” “Circular burials would presumably provide opportunity for special recognition by the distance of the grave to the powerful center.”

Notable Interments: Timothy Meaher, owner of the last slave-ship, Clotilda; John L. Rapier, owner of the Mobile Register and postmaster of Mobile; Adm. Raphael Semmes, CSS Alabama captain.

Did You Know? Upon his death in 1859, Portier was buried in the catacombs of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception.

Church Street Graveyard | Mobile, est. 1819

Situated off Government Street, behind Mobile Public Library’s Downtown branch, is Mobile’s oldest remaining graveyard. A simple arched entrance and deteriorating brick wall ensconce the somber 5-acre field of oaks, palms and centuries-old stones. Raised tombs, indicative of French and Spanish customs and Mobile’s high water table, are common as are barrel-vaulted tombs, in which the body is above ground, and false crypts, in which the body is underground. Many graves are enclosed with fencing or curbing (a low stone wall), which was typical in most 19th-century cemeteries.

Interestingly, the city’s oldest existing graveyard wasn’t actually Mobile’s first. Church Street Graveyard replaced an earlier burial ground, Campo Santo (1780-1813), that was located where the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception stands today. Mobile’s boundaries expanded rapidly in the early 19th century, and Campo Santo’s location prevented new development. To free up space, most of the bodies were exhumed and moved to Church Street. Among those was 5-year-old Anna Newbold, who died in August 1817 and whose unmarked grave is said to be the oldest.

Notable Interments: Joe Cain, Mardi Gras revivalist; Eugene Walter, Mobile’s “Renaissance Man;” Gen. Edmund Pendleton Gaines, a hero of the War of 1812.

Possible Haunt: Does the ghost of Charles R. S. Boyington roam the graveyard? In 1834, Boyington stood at the gallows, accused of murder, declaring his innocence: “I am innocent, but if I am hanged, a great oak tree will spring up from my breast so that this city will never forget the wrong it has done to an innocent man.” The following year, an oak grew from his grave. In 1910, the cemetery’s walls were moved, leaving Boyington’s oak and a number of unmarked graves outside its boundaries.

Strange But True: In an effort to promote the cemetery’s revitalization and preservation, then-mayor Patrick J. Lyons had a playground built in the northwest corner of the cemetery, sometime around 1910. How long the playground lasted is unknown.

Shell Banks Cemetery | Gulf Shores, est. circa 1864

Along Fort Morgan Road, behind Shell Banks Baptist Church, lies Shell Banks Cemetery, gripping with it nearly 500 years of secrets. While the earliest date on the remaining gravestones reads 1864, the history of the site dates back to at least 1539, 81 years before Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock. An historical marker beside the church claims this area was the location of the Indian village “Achuse” and was the first to have been visited by a white man.

Its location on the Bay made Shell Banks a popular stop for explorers from Portugal, Spain, France and England. It was also popular among pirates of the 17th and 18th centuries. Stories abound of pirates’ violent and raucous behavior, such as using a magnolia as their hanging tree, throwing bodies into the Gulf and coming ashore during the night to bury their dead — or their treasure.

Possible Haunt: In the Baldwin County Historical Society’s July 1979 publication of “The Quarterly,” a contributor recalls, “I remember there were many tales of buried treasure, of iron pots and blazed trees. A ghost tree, where many had heard groans and screams, was given wide berth at night. Many fishermen passing close by, upon hearing the noises, would quickly row out into the deep water.”

More to Explore

Stockton Memorial Cemetery | Bay Minette, est. circa 1825

Those who settled Stockton in the 1700s are buried here, one of the oldest cemeteries in Baldwin County.

D’Olive Cemetery | Daphne, est. circa 1826

The D’Olives, one of the oldest families in Baldwin County, arrived around 1770 from Toulouse, France. It is not known how many people are buried in the one-acre cemetery.

Spring Hill Cemetery | Mobile, est. 1844

Over 1,000 people are interred here, including those long-recognized names such as Toulmin, Austill, Ladd and White-Spunner.

Confederate Rest | Point Clear, est. circa 1861

There are no signs directing visitors to this resting place, which is located behind Lakewood Golf Club amidst large oaks. Buried here are more than 300 soldiers who died in the Grand Hotel — when it served as a hospital.

Little River Cemetery | Bayou la Batre, est. circa 1780

One of the oldest cemeteries in Alabama, all that remains are faded and hurricane-damaged headstones. Locals claim funerals from earlier centuries were held on boats, with the coffin being brought down afterward for interment.

Old Searcy Hospital Cemetery | Mount Vernon, est. unknown

Entrance to the cemetery is patrolled by a security guard, with access only given for legitimate reasons. Presumably, the graves, marked by numbers, not names, belong to former hospital patients. There are no known burial records.