Dated December 13, 1925, the historic letter from Mobile was short: “Please inform me if you have a local branch of the NAACP. If you do not have a branch here, please inform me what requirements must be met to become an organizer.” With no more than these few words, 22-year-old John LeFlore announced his intention to become a civil rights organizer. The letter set the trailblazer’s course, a consequential life that reshaped twentieth-century Mobile.

LeFlore was born in Mobile in May 1903, the youngest of five children. He never knew his father. A laborer at a railroad depot, Dock LeFlore died before his youngest son’s first birthday. His mother, Clara LeFlore, took in laundry and was a mainstay of the AME Zion Church. Summertime often found her in Clarke County, Mississippi, helping tend to her family’s small sassafras grove. The LeFlore children went to work at an early age. By the time he was six, John LeFlore was selling newspapers along the Mobile waterfront with his brother George. On more than one occasion, he was accosted by white passersby for reading instead of selling.

John LeFlore married schoolyard sweetheart Teah Beck in 1922. In Southern parlance, one might say that LeFlore “married up.” His new father-in-law worked at the post office and helped LeFlore study successfully for the civil service examination. The position afforded some protections from the daily difficulties of working in a segregated society. Still, indignities were ever-present. At the start of their honeymoon, the newlyweds were denied accommodations in a commodious sleeping car that the fastidious LeFlore had reserved. The cars were for white passengers only, the conductor insisted. LeFlore received rougher treatment on a Mobile streetcar sometime thereafter in a scuffle with a white patron over a seat.

These incidents, and likely others lost to history, served as the backdrop of LeFlore’s letter to the NAACP. He received a quick reply from New York. The Mobile branch established in 1919 had been dormant for several years and would require a new charter. LeFlore set about obtaining the necessary 50 signatories for the effort. It was important work, he told the NAACP official, “a duty to my race.”

The men and women who signed the charter were a snapshot of early twentieth-century-Mobile’s emergent African American middle class: postal employees, teachers, tailors, salesmen, carpenters, undertakers, porters and medical practitioners. Insurance manager Wiley Bolden was chosen to serve as branch president. LeFlore was the secretary, the lifeblood of the organization for the next three decades. “The going was painful and slow,” Bolden recalled. “Sometimes we didn’t have enough money to buy postage, but we didn’t stop the fight.”

The branch doubled in size within 18 months. In 1929, amidst the Great Depression, Mobile’s NAACP accounted for 80% of all the money raised by the organization in the entire state. Under the banner of the NAACP, LeFlore campaigned vigorously for funds in support of causes great and small, including the defense of nine African American youths arrested in upstate Scottsboro.

There were leaner years, too. In 1934, the branch sent less than $5 in contributions. The work that LeFlore undertook was often dangerous. It took a toll on him, his young and growing family and his colleagues. On occasion, LeFlore was poorly served by his own youthful zeal, ambition and frankness. He did not hide well his views of the shortcomings of the national branch, its well-paid officials or other civil rights organizations he felt were less committed.

“I believe our records will show that we have disappointed you more than any other branch in the country,” a terse NAACP administrator wrote to LeFlore in 1936. The Port City activist responded in kind. Things looked rather different for civil rights workers in the Heart of Dixie, he said. “Perhaps we are not as patient as you think we should be,” LeFlore wrote, “because we are desirous of trying to remove by vigorous and determined action some of the many evils which keep us in the muck and mire.”

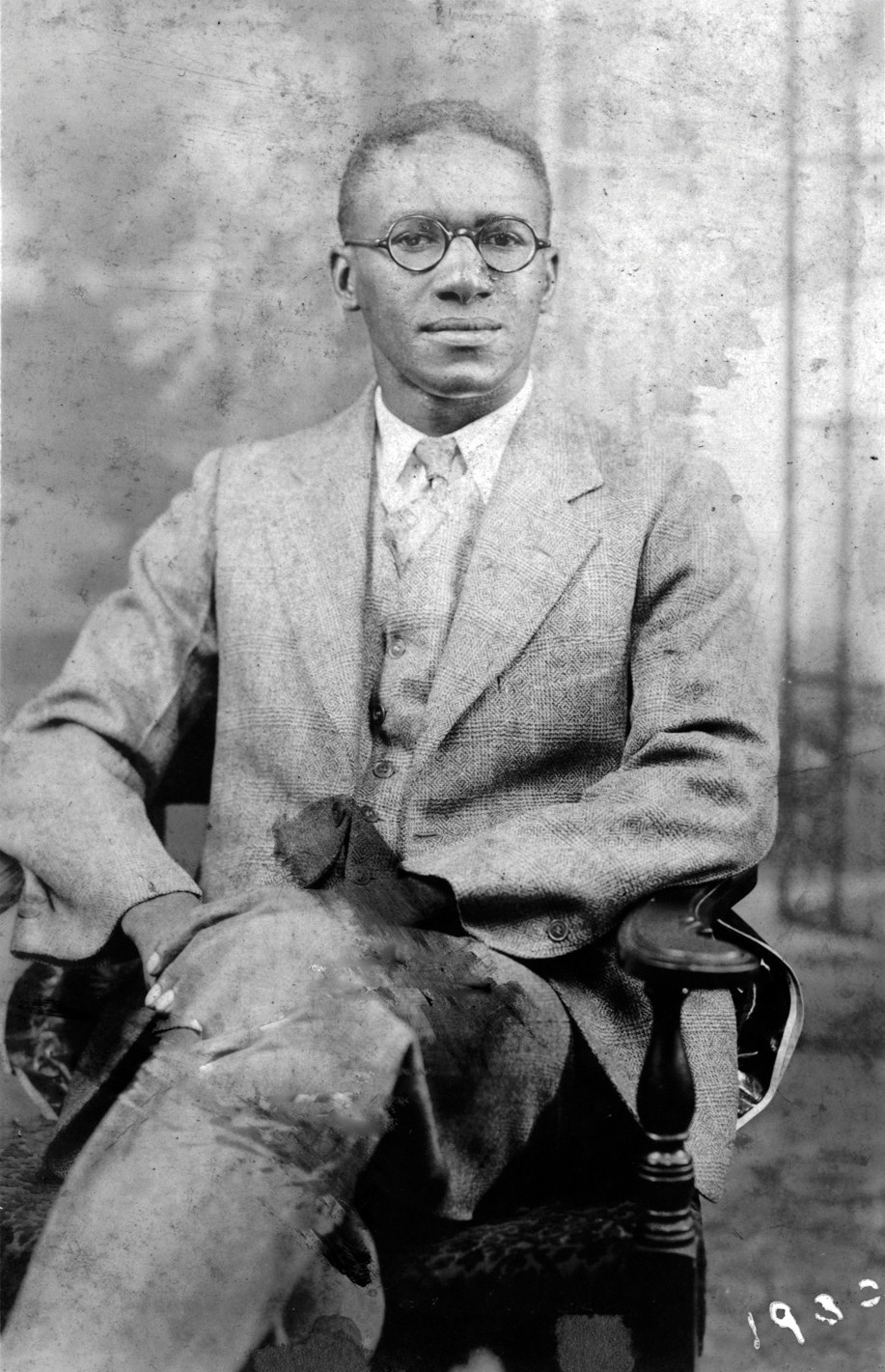

A worn, circa-1930s studio portrait provides a glimpse of this young LeFlore. The portrait was pinned to a letter he sent to Clara LeFlore. In it, he wears a linen three-piece suit. Arms and legs crossed, the bespectacled activist sits straight-backed and stares directly into the camera lens. It is a picture of dignity and poise amidst an uncertain time, of a man, in his own words, “vigorous and determined.”

“It really takes a person who is imbued with a love of human freedom, justice and liberty to stick as a branch worker of [the] NAACP,” he wrote to a friend in the mid-1930s. “It is a fight of fights.”

We can learn much about the John LeFlore that Mobile remembers by looking at his formative years. The child who was told he should not be allowed to read a newspaper became a correspondent for some of the best-known African American newspapers and an associate editor of the Mobile Beacon. The newlywed who was denied basic courtesies on public transportation devoted decades of his life to challenging segregation on trains and buses. The dreamer whose ambitions to study the law went unfulfilled became the architect of the legal strategies to integrate Mobile’s municipal golf course, public library, school system and eventually its halls of government.

From his early steps to reorganize the Mobile NAACP in the mid-1920s to his death in January 1976, LeFlore devoted 50 years to his civil rights work. The length and breadth of that work is remarkable: during the hard days of the Great Depression when help came from but a small, close few; through the forges, waterfront battles and boycotts of World War II; in moments of legal and political triumph often bookended by violence and setbacks; through the outlawing of the NAACP and the rise of his grassroots Non-Partisan Voters’ League; in times when the city and state he had always called home illegally deprived him of his rights as an American citizen; through years of struggle and striving, days of rage and hope. “I’ll keep at it as long as I can,” LeFlore told a reporter after the unsolved bombing of his home in 1967. “It’s a part of me by now.”

A century ago, a young John LeFlore decided to step forward and work to make his community a better place. Choosing to do what he felt was right, what was just, he entered into a lifetime of civic and political engagement. Fifty years ago this month, John LeFlore was buried. Today, may his life be a reminder to us all of the good that one determined person can do, once they decide to start, and once they decide to keep going.

Writer and historian Scotty E. Kirkland is the author of a forthcoming book on politics and race in Mobile. This article is amended from his remarks inducting John LeFlore into the Alabama Men’s Hall of Fame on September 16, 2025.