As speaking trumpets go, it isn’t much to look at. A silver bagatelle — tarnished, battered and only six inches long. In fact, if its owner’s wartime portrait may be believed, it was almost completely engulfed by his hand. Yet this little device, meant to project authority across a crowded deck or roiling seas, saw two years of steady service on board the CSS Florida, one of the Confederacy’s most successful commerce raiders.

The speaking trumpet was invented in the late seventeenth century by Sir Samuel Morland (1625 – 1695), an English diplomat, mathematician, and tinkerer. In his 14-page study, “Tuba Stentoro-Phonica: An Instrument of excellent use, as well at Sea, as at Land (1671),” Morland shared the results of his experiments with differently sized and shaped speaking trumpets. One 20-foot-long model projected a man’s voice up to a mile in foul weather, or so Morland claimed. He even went so far as to assert that, “sufficiently enlarged” and given a “favorable wind,” a speaking trumpet might be effective at eight or 10 miles! Despite his obvious enchantment with the invention’s reach, Morland also explained its utility at closer range. “In a Storm, it is of great use in a single Ship,” he elaborated, “that one mans Voice giving orders for governing and steering the Vessel, may be heard distinctly by all Mariners.”

This, we may be sure, is how Lt. Stone employed his trumpet on the Florida (depicted below in hot pursuit). Sardine Graham Stone Jr. was born at Bladen Springs, Alabama, on February 4, 1841, the son of a steamboat captain with the same salty moniker. Stone Jr. entered the U.S. Naval Academy in 1857, but the Civil War prompted him to resign and return South. Alabama Governor Andrew B. Moore appointed him a first lieutenant in the state’s Revenue Cutter Service (essentially an early coast guard), and shortly thereafter Confederate President Jefferson Davis made him a midshipman in the embryonic Rebel navy. Stone had served on several vessels, including the ram Baltic in Mobile Bay, before being assigned to the commerce raider Florida in November 1862. This sleek steam vessel, with her raked masts and twin smokestacks, had brazenly dashed into Alabama waters a few months earlier amid a rain of Federal shot, to Rebel joy and Yankee embarrassment. When Stone boarded her, she was undergoing repairs, provisioning, and arming prior to an escape attempt.

Stone was welcomed by the Florida’s captain, John Newland Maffitt, a seasoned and fearless sailor whose cap sat at a perpetually jaunty tilt. Maffitt sized up his new officer and immediately approved. “Mr. Stone has joined,” he wrote to his daughter. “He is intelligent and will make an admirable officer.” Lt. Stone served as navigating officer. It was in this capacity that the little silver speaking trumpet would have been invaluable, constantly in Stone’s grip and frequently at his lips as he bellowed instructions regarding ropes, sails, and steam.

Fully crewed and provisioned, the Florida ran out during the wee hours of January 16, 1863. It had been a squally night with big rollers, but by 2 a.m., skies were clearing, and a light mist clung to the sea surface. Maffitt determined that it was time, and the Florida edged toward the pass, burning coke that left no telltale smoke. Men were positioned aloft, ready to release the sails at a moment’s notice, and at the deck guns, should any blockader be so bold as to intercept them. Maffitt stood at the rail, Stone nearby, his speaking trumpet almost certainly clasped tightly at his side. As Florida glided silently through the scattered blockading fleet, one of her sailor’s likened her to a “phantom ship, manned by spectres.” At that critical moment, the coke gave out, and the engineer switched to coal, showering sparks from the funnels. Union signal lights instantly flashed the alarm, and Maffitt ordered all sail and full speed ahead. Stone’s services would have been critical at this time as he traversed the deck shouting orders and assessing their execution with an eagle eye. The ship positively bolted out of Mobile Bay, “off like a deer,” in the words of one crewman.

The Florida subsequently went on to an extraordinarily successful career: She captured and destroyed 37 United States merchant ships, costing American mercantile interests millions of dollars. Her daring run out of Mobile Bay was one of the war’s most dramatic episodes, and the little silver speaking trumpet carried by its oddly named owner played a most important part.

John S. Sledge is senior architectural historian with the Mobile Historic Development Commission and a member of the National Book Critics Circle. He is the author of “The Gulf of Mexico: A Maritime History.”

“A History of Mobile in 22 Objects” by various authors

Click here to purchase

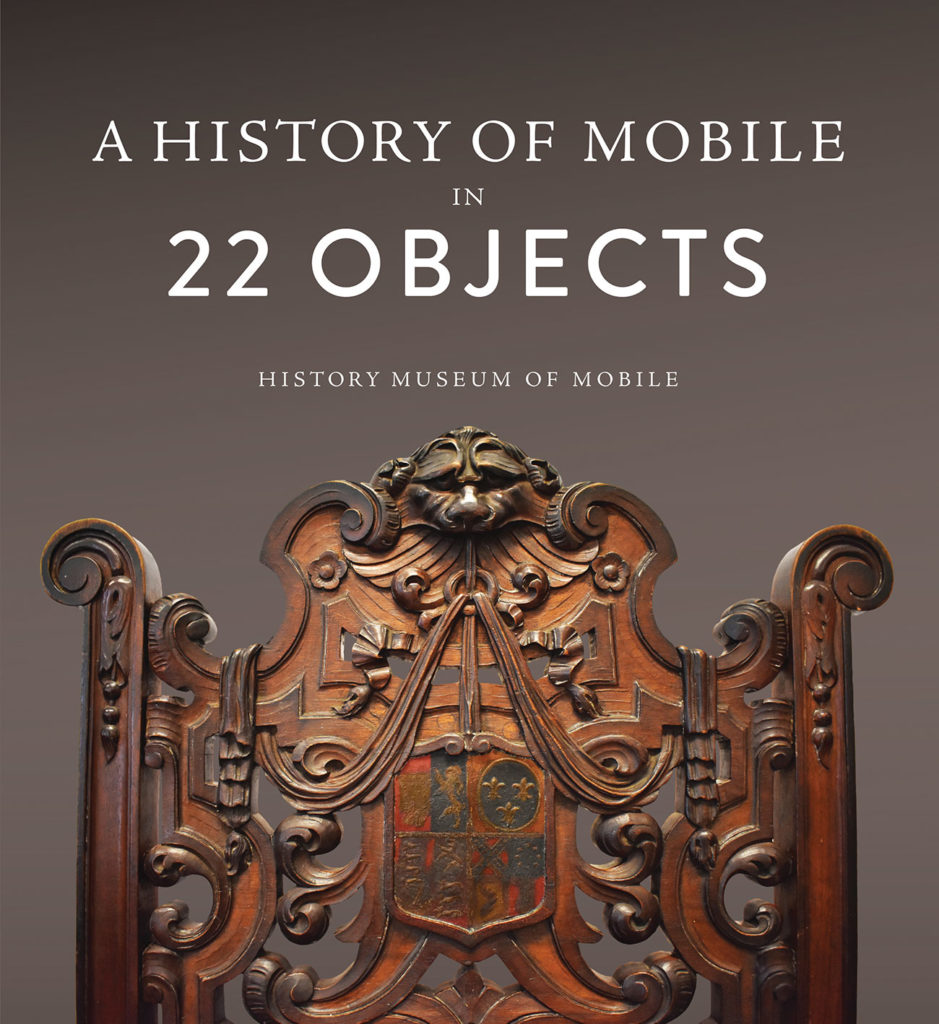

Released in conjunction with the History Museum of Mobile exhibit, this photo-heavy compendium delves into the city’s history through the analysis of 22 artifacts by Mobile’s leading researchers.