Mobile’s first baseball field appeared in 1860 at Spring Hill College, and in the 1880s, a popular field arrived down the Bay at Frascati Park. J. Howard Wilson added a baseball diamond to Monroe Park around 1901, and it was the city’s most popular field until a hurricane severely damaged it in 1926.

Monroe Park had been created as a destination for riders of the city’s electric streetcar system. By the mid-twenties, ridership was steadily dropping as automobiles became cheap and plentiful. When Wilson was approached by the Mobile Baseball Association about building a replacement field, he would offer the group no more than a two-year lease, so they looked elsewhere.

Hartwell Field

Mobile’s then-mayor, Charles Hartwell, was a major baseball fan, and he led his fellow city commissioners to offer 26 acres of city property at the intersection of Tennessee and Ann streets. By March 1927, a new baseball park, Hartwell Field, was dedicated in honor of the mayor who had made it a reality. The site was equipped with a 1,000-car parking lot, and over 9,300 Mobilians jammed the park on opening day.

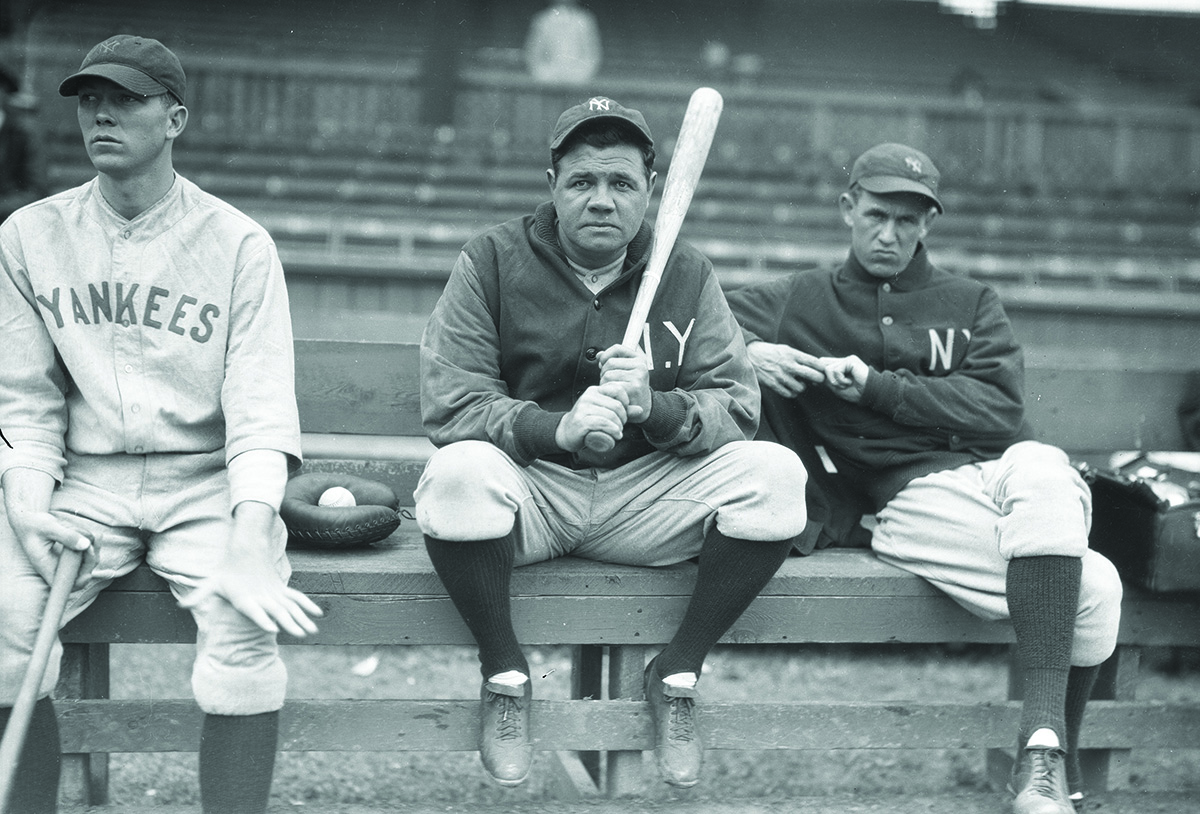

America was baseball crazed in the 1920s, and two of its biggest stars, Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, played exhibition games at Hartwell. At first, afternoon games were the norm, but lighting in the 1930s allowed for night games. Stands were regularly filled with up to 6,000 fans. In 1952, the city spent $25,000 on upgrades for the park, including a new roof for the grandstand.

Langan’s Folly

Just seven years later, the city condemned the park’s bleachers. Their wooden design was similar to those that had collapsed at Ladd Stadium, and Mayor Joe Langan pushed to have the stadium rebuilt with a concrete and steel superstructure at a cost of $1 million. Rededication was held on July 11, 1959, and local pundits termed it “Langan’s Folly.”

Timing could not have been worse. Game attendance began to plummet in the early 1960s, a change blamed on the popularity of television and newly organized youth baseball leagues. By 1963, city commissioner Charles Trimmier termed it a “white elephant” and offered it to the state for livestock shows and agricultural exhibitions.

For several years, it housed the annual Greater Gulf State Fair and hosted visiting circus troupes, wrestling matches and even drag races. Area Catholics used it for May Day celebrations and candlelight services.

In 1966, a new baseball team arrived from Birmingham, but few came to watch. The infield, which had once been described as pristine, began to deteriorate.

A Sad Ending

In July 1979, the city considered demolishing the park and using the property to expand Magnolia Cemetery. Estimates of $540,000 for needed repairs and another $300,000 to run it annually made the profitable sale of cemetery lots look attractive.

Hurricane Frederic arrived that September and peeled off the roof of the grandstand and destroyed the press box. By 1980, the cost of repairs, along with an additional $150,000 in damages from vandals, sealed its fate.

In 1983, the site was in the running for a new metro jail, and wreckers came and cleared the space in just 45 days. Ultimately, the jail was built south of Interstate 10, and the property today remains largely unused, except by the city’s mounted police department and their horses.

With the recent departure of the Mobile BayBears and the woes facing Hank Aaron stadium, Mobile history seems to be repeating itself.