Lights flood the stadium, and spectators adorned in their team’s colors cheer from the crowded seats. It’s halftime, and the football players have retreated into the locker room. Who continues to keep the fans invigorated with the fervor of the game? It’s the mascot – dancing, jumping and gesticulating his way into the hearts of thousands. The love for these plush incarnations of sports icons is universal. And for those wearing the masks, nothing compares to the thrill of the performance and the exhilaration of becoming one with the characters they play.

Mac the Ram: Sweet, Lovable Ewe

Nowadays, Josh Farmer serves as development officer with Mobile’s Alabama Baptist Children’s Home. But in 1999, he needed money to attend the University of Mobile. That’s when he heard about the school’s $1, 200 mascot scholarship.

“I studied the ways of the ram, ” Farmer recalls. “I learned Mac’s persona, developed skits, readied myself for the competition.” On audition day, he was psyched, prepared, confident – and the only one to show up. He became Ram by default.

In addition to representing the University of Mobile and putting on hilarious skits and performances at school events, Farmer reveled in secrecy. He notes, “Wearing the ram enabled me to play jokes on good friends who never knew it was me.”

|

The Auburn Tiger and the Fairhope Friend of Aubie

Let’s just say Fairhope native Justin Shugart ran in the same circles as Aubie from 2006 to 2008. “Actually, I was a ‘Friend of Aubie, ’” the now-Birmingham resident says. Because no one reveals Aubie’s identity. And with fewer than five annual members, “Friends of Aubie” is Auburn’s most secretive club.

“Friends of Aubie” are selected annually based on GPA, skill tests and the grueling Aubie Clinic. Auburn University frankly states on its website, “Trying out for Aubie is no easy task.” And once you get the gig, staying on means keeping it secret.

Of the “friends” chosen to assume Aubie’s identity, the only people on earth privy to the knowledge of who is in the suit are the alternates who are not. AU emphatically states, “No one should know that you are part of what makes Aubie so special.”

Shugart now works as the executive director of the Alabama Northwest Florida Chapter of the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America and is still a “Friend of Aubie” in spirit. “Most people associate mascots with athletics, ” he says. “But Aubie serves a far greater role as the goodwill ambassador across the Auburn family. I enjoyed learning the impact one person or one act can have on someone’s life.”

After all, that’s what friends are for.

ABOVE Sarah Parker Roebuck gives Big Al life as he lollops onto the scene, dancing and performing all the way.

Crimson Dreams for a Satsuma Girl

As the 2005 to 2007 school mascot for the University of Alabama, Sarah Parker Roebuck entertained stadiums of 90, 000 spectators (and millions more on national television), escorted Joe Namath and high-fived Condoleezza Rice. And they never knew it was Roebuck under the mask.

“It’s like being Clark Kent, and you can’t tell anyone you are really Superman, ” Roebuck shares with a laugh about her once-secret identity. But the Satsuma resident and stay-at-home mother of two small children adds, “I would not trade anything for my days as Big Al.”

She became the Alabama icon after tryouts, interviews and a four-day clinic. “We learned Al’s personality, walk, demeanor and character, ” she says. “If you see him, notice how Al walks swinging his head from side to side. It’s not just to be cute. It’s the only way Big Al can see his surroundings.” The large elephant head, three feet in diameter, offers no peripheral vision.

Those who don the iconic elephant’s costume never refer to it as such, and oftentimes the suit becomes a way of life. “Al is ‘he’ and you become ‘him, ’” Roebuck says. “This is embarrassing, but one day on campus, I saw children and approached them. I acted all silly, doing my elephant walk, shaking hands, clowning, playing. And then I realized, I wasn’t in the suit.”

Even today, Sarah often thinks about her Tuscaloosa counterpart, especially during football season when she sees Big Al on TV. “I’ll reminiscence, ” she smiles, “and then while looking at him on the screen, quietly say, ‘Hello, buddy.’”

Fun fact: Mobilians Craig Cantrell and Paula Kiszla served on the committee to select the design for the original Big Al costume, which debuted in the 1980 Sugar Bowl.

A Lion Roars in Foley

Originally, Foley High School’s athletic teams were known as the “Orange Eaters, ” because, according to Foley historian Keith Smith, the football team allegedly raided area orange groves and feasted upon the ill-gotten fruit.

In 1928, they became the Lions because it sounded more ferocious. Not to mention, the cheerleaders no longer had to awkwardly shout, “Let’s go Orange Eaters!”

From 2001 to 2003, Stephanie Cody was Leo the Lion. “It was so much fun, ” Cody remembers. Today, she teaches at the same Foley High School where she once wore the costume.

This proud campus community searches out mascots with insane energy and enthusiasm. In other words, they don’t want to find their lion lyin’ down on the job.

“I tell current Leos to have fun, but know your audience, ” Cody says. “Anyone can wear an animal suit and wave. But you are a performer. The crowd can’t see you in the costume but they can sense emotions.” She adds, “Don’t be timid. No one wants a cowardly lion!”

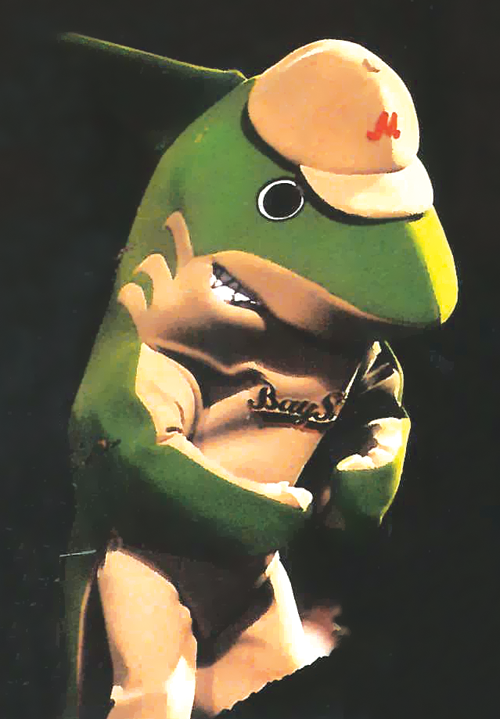

ABOVE LEFT Charlie Gray, the one and only Mobile BayShark, flexes his shark muscles in the costume he wore for the duration of the pro baseball team’s existence.

ABOVE RIGHT Occasionally clumsy but always endearing, Puck waves to the enthusiastic crowd of hockey fans.

Buddy the BayShark: A Fish Tale

Dauphin Island’s Charlie Gray remembers his 1994 hiring as the Mobile BayShark’s mascot, the hottest experience of his life — literally.

During baseball season at the Port City’s Stanky Field, a summer game at 90-plus degrees was the norm. Gray felt less BayShark and more grilled flounder. “I would take that shark head off and sweat would pour out, ” he recalls.

But Buddy the BayShark was no fish out of water. With zero mascot experience, he was a fast learner.

“Try to face the wind, ” Gray advises. “Even the slightest breeze blowing through the gaping shark’s mouth (the only opening in the suit) provided some cooling.”

And oh, how he boogied. “I can’t dance, ” Gray confesses. “But oh man, Buddy could. But you had to be careful: A quick turn of the tail could knock children off their feet.”

Despite brutal heat and wayward fins, Gray was Buddy for the BayShark’s entire run. Today, he lives on Dauphin Island and, fittingly enough, works as a fishing guide.

Puck the Magic Dragon

House lights down, spotlights up, all eyes on the ice. Puck, the Mobile Mysticks ice hockey team’s mascot, charges the rink – and falls down hard. A green dragon body slides left. His decapitated reptilian head shoots right. Children gasp.

Such was the life of a mascot on ice when Mobile’s Willis Willcox donned skate blades. “I had never ice-skated in my life before being Puck, ” he remembers and laughs. “Many of my ‘stunts’ were really unintentional.”

When interviewed for the Puck job, Willcox was questioned about his limited ice-skating skills. His answer: “I believe fans would enjoy watching him fall more than skate.” The interrogator agreed. Willcox was plucked for Puck.

As if being an ice-skating Mobilian isn’t hard enough, try doing it blind. “You are totally encapsulated and can only peer from mesh, window-screened eyeballs, ” he recalls. “Just standing on the blades was tricky, and I could hardly see.”

The pay was $50 per game during his 1996 to 2002 gig, but the dragon confesses, “I would have done it for free. It was worth it to see the children’s faces light up.”

Were you a college or high school mascot? Share your story below.

text by Emmett Burnett