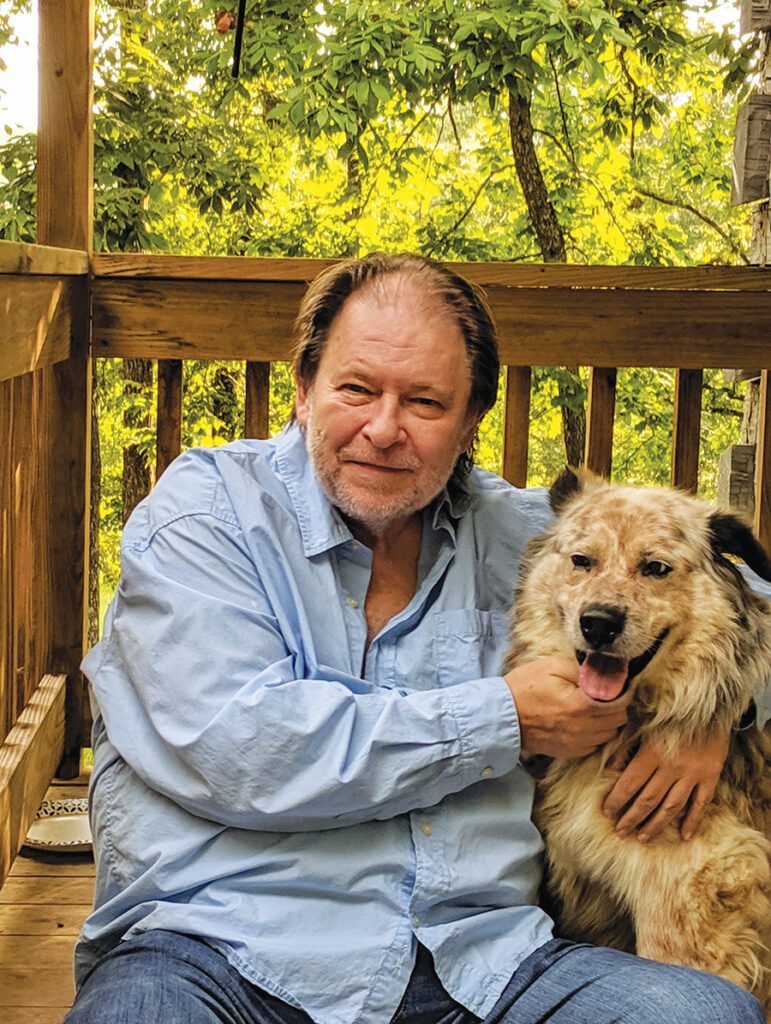

The first thing one does upon planning to interview Rick Bragg is to try and get face-to-face with the Pulitzer Prize-winning author. Interviews are more fun in person, we explained over email. Plus, it’d be nice to scratch Speck behind the ears.

“Speck don’t travel well,” Bragg said from his farm in northeast Alabama. “He tries to eat the truck.”

Speck, who Bragg found as a half-blind, half-starved stray on the mountain ridge behind his home, has no way to defend himself against such slights and accusations. But even if just half of Bragg’s stories in his new book “The Speckled Beauty” are true, Speck is undeniably, irrefutably, hand-on-the-bible not a good boy — and Bragg loves him for it.

Writing, or as Bragg describes it, “the practice of leaning one word against the other so that they don’t all fall down,” has helped the author navigate the twists and turns of life. Now, he’s got a dog for that.

An Interview with Rick Bragg

Well, it’s always a good day when we get to talk about a new Rick Bragg book. You wrote in the introduction to “The Speckled Beauty” that you’ve always wanted to write a book about a dog, and it sounds like you’ve had a lot of them over the years. What was it about Speck?

The only way to write a dog book is to read a lot into the dog, ‘cause dogs don’t give very good quotes. Or maybe I’m not listening good. But I’ve never seen a dog so capable of just making life better. I guess all dogs do. I guess all dogs in the worst of times come up and lay there, head on your knee, and life just gets better.

But Speck is different. Speck can determine when he walks into the room who needs him the most. And at varying times, it was me and my mama. And, of course, when my brother Sam got really sick, Speck knew that instinctively and kind of just abandoned me and glued himself to Sam. Because he figured out who needed him the most.

Dog people tell me that that is just usual, that’s just what happens with a good dog, but I haven’t had a dog of my own — just my dog. There have been family dogs, a lot of really great family dogs, but this is the one I went and got, you know? I went and got him on that mountain when he was starving to death, so he’s mine.

We were saddened to hear about the death of your brother Sam in April. Like many readers, we felt we knew him personally through your stories. There are plenty of wonderful “Sam moments” in this book — which is your favorite?

There are some that I’ll always remember. One of my happiest memories in this book stems back to an incident that occurred before we knew Sam was sick and I could still get mad at him. I don’t think people understand what a great luxury it is to be able to get mad at somebody, you know?

But in the book’s introduction, I wrote about the day I came home, and Sam started telling me why Speck was in dog jail. He just started this litany of things the dog had done: peed on the tractor, peed on Mama’s flowers, run the cats, stole the cats’ food, cats flyin’ everywhere, chased the donkeys ’round and ’round in a circle and don’t think he even knew where he was taking ’em. And just one thing after another, after another, after another — and just this disdain in his voice for the dog. My dog.

Then a few years go by, and Sam’s sitting outside with one big hand on the dog’s head, kind of at peace in a bad time. And that just made it a little better.

Did any classic dog literature inspire how you approached telling the story of Speck?

Well, the first thing I did — and I shouldn’t have done it — was I went back and re-read “My Dog Skip” by Willie Morris, which was a simple, happy and delightful story about a boy and his dog. It was not about an old gimpy man and his dog. It was about a boy and his dog and the joy that that brings. There was just this happiness there.

I don’t mean this to sound arrogant, but the prettiest writing in the book is just a simple paragraph where I say, “A boy should have had this dog, a tireless, terrible, indestructible boy. Every bang of the screen door would have been the start of a great race. Think of the mud puddles, alone. Think of the adventures. The days would flash by, time would catch fire.” And I think that regret over being an old man with a dog like this is probably the truest thing in the book.

During the year, when you’re teaching writing in Tuscaloosa, where is Speck? I get the feeling neither of you particularly like being apart for too long.

I’m in northeast Alabama at the farm with Speck most of the time, and I commute over to Tuscaloosa to teach. Someday, I hope to commute down to my place in Fairhope and spend some time again, if I can remember the way.

Any food you really miss down this way?

I’ve eaten a lot of lunches at a place out on Highway 32 in Fairhope called Saraceno’s. They have fresh vegetables and good fried chicken. I tell myself that really, really, really good fried chicken is actually not bad for you. Only bad fried chicken is really bad for you.

But Speck’s not much of a traveler?

No. Quite frankly, he knows that if he gets in the car, he’s going to the vet. And he knows that if he goes to the vet, they’re going to give him shots and they’re going to give him pills. I try to slip him his pills at home, but he won’t eat ’em. I mean, he knows it’s medicine. If you hide it in a chicken liver or you hide it in a ham sandwich, he will eat around it and leave it sitting there, just shiny. He knows that when I take him to the vet, they’ll literally stick their arm down his throat to get that pill in him. Remember those old cartoons where you’re trying to move a dog or cat and they’ll put one leg on each side of the window seal or doorframe — he’s like that! I mean, he knows that if he puts all four legs in the corners of the doorframe, then I can’t get him into the truck.

But coming home from the vet, he just hops in there like a show dog. He knows that coming home it’s treats, Greenies, pats on the head, my mama telling him what a good boy he was, what a good brave boy.

Speck’s part Australian Shepherd, and I read in a book that they’re supposed to be as smart as their owners. I know damn sure he’s smarter than I am.

On the subject of intelligence, or better yet wisdom, do you think there’s anything we can learn from our dogs?

It’s funny, you can raise your voice to this happy, ridiculous, brain-dead tone, saying, “Who’s a good boy?!” and a dog will pop around, and you think, That’s just the dumbest creature on the planet. But how does a dog walk into a room and know where the deepest well of sadness is? I don’t think we’ll ever know exactly why they do what they do, but the one thing I’m absolutely certain of is that they are a tuning fork for sadness.

I think that’s also true for my dog, until a squirrel walks by. Then all bets are off.

How do you think they decide which squirrel is worthy of their attention? Speck will almost let one run across his field of vision, and then he will all of a sudden decide that this is the most important squirrel in the history of squirrels.

If you could talk with Speck for 30 seconds, and he could understand you, what would you tell him?

I would get right in front of his face, and I would tell him, number one, stay away from the barbed wire. He runs full tilt toward the barbed wire, chasing cats, deer, turkey; he runs wide open at it and ducks at the last second. This is a one-eyed dog. So I would tell him, first of all, just be careful. Be a little bit careful.

Second, I would tell him that he doesn’t have to fret every time I walk out the door or every time I get in my pickup. I have to tell him every time, “I’ll be right back, I’ll be right back.” If I’m going to the airport, I’ll tell him that I’ll be gone a day or two and, oh, he’s just heartbroken and dismayed. He’s tried to crawl into a town car and then herd it back up the driveway.

Mom has taken to lying to him. I drive into Jacksonville, Alabama, every day and have some lunch, take my notepad, get my thoughts together, just have a few minutes of quiet without having to empty a bag of horse feed or whatever. And Speck, of course, gets upset every time that I go out the door. And my mother has taken to lying to him and saying, “He’s going to get you something to eat!” And he actually seems to perk up a little! Now, I can’t make my 84-year-old mother a liar, so what do you do? You go and you bring him home a corn dog or some bacon. God, it’s complicated having a dog.

I’d just tell him, “Look, buddy, you’re not ever gonna be left alone again. You’re not ever gonna have to fight for a bite to eat. You’re not ever gonna have to fight for a place to stay. All you have to do is live.” If I could get him to understand that … because I think he knows I love him. I think he knows that.

What do you think Speck would say back?

He would probably tell me, “Well, dumbass, shouldn’t it be clear what I want? I want a Greenie or a Milk-Bone or both. I want some people food because whatever scientist said that people food is bad for dogs didn’t discuss it with dogs. I want some scrambled eggs, and I want you to run out in the yard and play with me like I’m a puppy and you’re not a decrepit, broke-down, old, gimpy man.”

Once the book is released, how do you think Speck will react to all the new attention?

He’s a little bit of a ham. If rolling over on his back and pretending to swim upside-down will get somebody to laugh, he’ll do it. So there’s no telling what kind of monster we will create.

Do you already have your next project in mind?

Everyone asks, and I’m grateful that they do ask, why I haven’t done a novel, and the answer is pretty easy. I always thought I had something to say about the people where I grew up. There seemed to be an appetite for that that did not wane. But I can’t write about my people in a long-form book anymore. Maybe someday I’ll be able to write about Sam … I realize now with a certain amount of shame that I often wrote about death as a new adventure, as a drama, and that’s just not what it is. It’s just a damn awful, black, miserable pit. And I don’t think I can try to write pretty about people as close to me as my brother.

So, what do you do then? Well, I guess you do a novel. And you’ll try to do a novel that contains things you know something about. It may be about the people of the foothills of the Appalachians. I don’t want to necessarily write another Depression-era novel. I think what’s kind of missing are really good novels about the modern-day South. So, it may be located in the mountains, or I may do something I’ve always wanted to do, which is write a novel that’s set on the Coast. I’ve always wanted to step outside the foothills of the Appalachians and write about the Coast — write about those rivers that snake through those green tunnels down there, where you’re just as likely to see an alligator as a bull shark. Write about the struggle of living and dying among working people down there. I don’t know them down there the way I know the people up here. I didn’t grow up with them, but I think as a scene, as a scene, I would love to tackle the Coast. My friends there, Skip Jones and Sonny Brewer and them, have wonderful stories to tell about boats — just boats. And I’d like to turn a little boy loose on that.

I’ve always been fascinated with white sand and blue water, but down there, on that side of Mobile Bay, there’s a murk to it. There’s a murk to the water, and you just wonder about all the things that are hidden by that murk. So yeah, I think I could probably pull a novel out of that somehow.

Well, we appreciate you taking the time to answer our questions, Rick. We didn’t mean to keep you for this long.

This is my fault entirely. I guess the bottom line is, I don’t know when to shut up when it comes to talking about Speck. He may not be the best friend I’ve ever had, but he’s the most constant one. He’s the one that I needed the most right now. And I’m really lucky that he chose our mountain.

I’ve got to go on a little book tour when the book comes out, so Mom’s already thinking up ways to bribe Speck to keep him from going crazy, but I won’t be away long. He’ll be fine.

Rick Bragg’s “The Speckled Beauty,” set for release on September 21, will be available for purchase locally at The Haunted Book Shop in Mobile and Page & Palette in Fairhope. Visit pageandpalette.com to purchase tickets to a limited seating event with Bragg on September 28.