Sea shanties (also known as chanteys) were slow-paced songs which gangs of working men — or “shantymen” or “shantyboys” — sang to pace the hard work. On ships, these songs helped the men crank the windlasses, raise the anchor and set the sails, all hard work done by groups of strong men before steam engines and “donkey boilers” replaced them. Mobile’s own antebellum longshoremen loading cotton in sailing ships were a major part of the creation of these folk songs.

Before the Civil War, the Gulf Coast ports were major exporters of cotton bales to England and France. Mobile’s own Harriet Amos Doss says in her work, “Cotton City: Urban Development in Antebellum Mobile, ” that our local cotton exports at that time surpassed Charleston, Savannah and every other port except New Orleans (New Orleans got North Alabama’s cotton via the Tennessee River, plus Louisiana’s and Mississippi’s supply).

|

The cotton would be loaded on flatboats or steamboats at landings all up and down the rivers. An 1855 print from “Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion”, opposite top, shows bales sliding down the old cotton slide from the bluffs at Claiborne to the Steamboat Magnolia at the bottom of the slide. In a “triangular trade” from Mobile, the cotton was mostly shipped to Liverpool for British cotton mills. Those ships then brought immigrants from England to New York, and goods for the planters and city folk from New York to Mobile. (The main shipping line after 1830 was the Hurlburt line, and Mobile’s Cowbellions are said to have started when Michael Krafft got tipsy with the captain of a Hurlburt ship in the Christmas and New Year holiday season and went off with rakes and bells.)

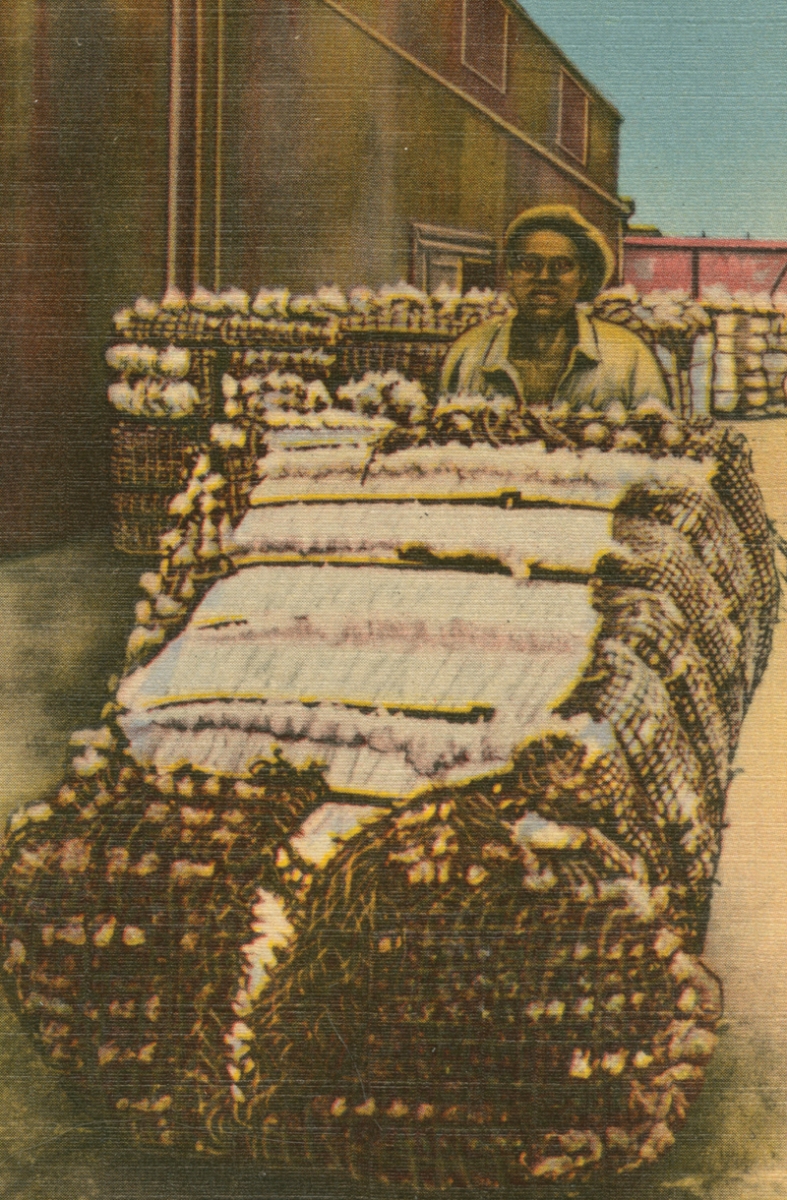

The tighter the cotton was packed, the more money the shippers made. When the cotton bales got to Mobile, they were too loosely compacted to efficiently ship. Men and steam machines would compress the bales so that they were more tightly bound. The cotton compresses were major businesses in Old Mobile, but as a second step, for maximum efficiency, the men also used giant “jackscrews” to force these tight cotton bales into the cargo holds of the sailing ships.

Most have assumed that these workers were mostly black, whether slave or free. But it turns out that research from a 1951 book by W.M. Doerflinger, “Shantymen and Shantyboys, ” explains that many of them were white Irish sailors in the North Atlantic packet trade who didn’t want to cross the North Atlantic in sailing ships in the winter. Instead, lots of them came to Mobile and New Orleans for the winter job of “screwing cotton, ” or forcing the bales into the cargo hold, which was said to be a hot and demanding job. This was just a seasonal job, since the cotton was harvested in the fall then compressed and loaded on the boats in winter.

Doerflinger tells us that while these white Atlantic sailors were here for the winter working, they worked side by side with black workers. Thus the white sailors were exposed to the land-based working songs of the local black workers and tended to blend the black and white music and lyrics together. They also say that the white workers were exposed to music in Mobile’s theaters — black spirituals and revival music — and in what can still be called, for historical purposes, “negro minstrel” shows. The result was a blended work song, and Mobile played a major role in that creation.

ABOVE An 1855 print from “Ballou’s Pictorial Drawing Room Companion” shows tightly packed bales being moved down the old cotton slide. Here is a similar slide.

Courtesy of Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery, Alabama

In his book, “Shanties from the Seven Seas, ” Stan Hugill says that by now it is impossible to be accurate about where any part of this or that shanty came from and that it’s best not to be dogmatic about it. Many of the verses were very dirty and many more we would today consider clearly racist. But it’s certain that the Port of Mobile was named in the verses of several of these songs. For example, in the shanty “Roll the Cotton Down, ” one verse says: “I’m going down to Alabam’ to roll the cotton down, me boys.” Another says: “Was ye ever down in Mobile Bay, screwin’ cotton by the day?” and “Oh, Mobile Bay’s no place for me, I’ll pack me bags and go to sea.”

And in the shanty “Donkey Riding, ” the lyrics echo: “Wuz ye ever down in Mobile Bay, Screwin’ cotton all the day, A dollar a day is white man’s pay.”

So, should you ever hear the crooning of an old sea shanty, remember that part of it might well have come from right here, back in the 1840s or 1850s.

David Bagwell is a retired attorney and amateur historian living on the Eastern Shore of Mobile Bay.

Text by David Bagwell