I am about 7 years old, pajama-clad and holding hands with two of my sisters as we skip to the swing sets. The sun is slowly fading above the huge movie screen. We have about an hour to play before we scramble back to the car.

My parents’ strategy, shared by millions of others in the ’50s, was to let the kids wear themselves out before it got dark enough, around 8 o’clock, for the film to be shown. It worked. By the time my sisters and I finished our contraband home-cooked popcorn and watched a couple of cartoons, we were vying, like a litter of kittens, for a place to curl up. My father would turn down the in-car speaker and wait for the jumble of little girls in the backseat to nod off. Finally, he could be alone (almost) with his sweetheart at the movies.

Fast-forward a decade to 1967. Now I’m someone’s sweetheart. We double-date with our best friends to the Auto Show Drive-In. The admission is less than a dollar a person; even cheaper by the carload. The guys pay, and then we maneuver up and down the lines. We recognize 10 or 15 cars whose occupants we know, but settle on a secluded spot. Serious kissing is on the agenda this evening.

Before the second movie even begins, I’m panting. Ah, disapproving reader, it’s not what you think. The heavy breathing is due to the coil my date lit to ward off mosquitoes. Its smoke has triggered my asthma. I will leave the “passion pit, ” as my girlfriend Margie’s mother calls it, with my girdle intact.

In the last few months, when I’ve asked members of the drive-in generation to share their stories, so many tender memories and true confessions unfold that I feel sad for those who’ve missed iconic experiences similar to mine. Mobile’s last drive-in, the 550-car Bama, closed in 1986. But for three and a half decades, the outdoor picture show was a favorite, inexpensive amusement. It’s the place you had fun as a family. And, as a teen, it’s where you honed social skills and tried out love. There in the dark, surrounded by hundreds of others, you could find a new part of yourself and come of age.

|

THE ROLL OUT

America’s first drive-in opened in New Jersey in 1933. By 1948, there were 13 in Alabama. In 1949, the Bama Theatre, at 3251 Halls Mill Road at Darwood Drive, premiered in Mobile. However, the heyday for open-air theaters was the mid-’50s. The Auto Show, off U.S. Highway 90 in Mobile, and the Air Sho, in Chickasaw, each set up screens and speakers in 1955. The Do Drive-In, off Wilson Avenue in Prichard, followed in about 1960.

For a time, according to Kerry Seagrave, author of “Drive-in Theaters, ” outdoor theaters drew a million more viewers than traditional movies and twice the concession revenues. The gates opened early so children could play, and the bill of fare typically included a double feature, cartoons, a newsreel and, sometimes, contests or live entertainment. Audiences could be captured for four hours or more and tantalized with reminders about sno cones, hot dogs, “pizza, pizza, pizza!, ” ice cold drinks and popcorn. (Not everyone smuggled in their own treats.) It was an engaging, satisfying and, for a while, profitable enterprise.

SHOWING UP TO SOCIALIZE

“On a summer night, you’d drive up and down U.S. Highway 90, ” says Bruce McCrory (Murphy, 1968). “It was the Auto Show and then McDonald’s for a Coke and french fries. Sometimes you’d have a date, but you could also hang out with friends.” He laughs as he recalls one night. “Eight of us packed into Sue Bonner’s Ford convertible – five in the trunk – just to see if we could get away with it. We cruised the perimeter and left. Didn’t catch any of the movie.”

“There were movies?” chimes in an eavesdropping Bill Heath (Murphy, 1964). “I couldn’t see through the trunk.”

Nancy Mosteller Hoffman (Bishop Toolen, 1966) adds, “You’d run into 20 people you knew at the drive-in and at Ossie’s Bar–B-Que later. It was fun to chat until someone actually watching the show would hiss at you to hush.”

“On a nice night, a group of us might meet there, ” Jeffry Culbreth (Murphy, 1972) says. “We’d sit on the hood of the car and make jokes about the show. When we got too loud or turned the speaker on high to hear, cars might flash their lights at us.”

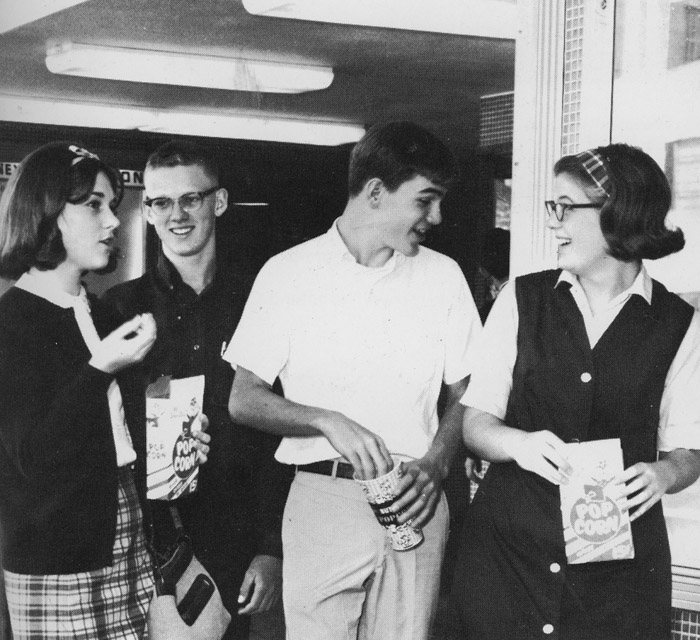

“We did much more talking than watching the movie, ” says Ann Giddens Green (Murphy, 1956), whose father, Kenneth R. Giddens, owned the Auto Show and the Air Sho. “The Auto Show had a porch in front of the concession stand. We’d linger there to see friends and hope that boys we knew would come by.”

“It was exactly like the movie ‘Grease, ’” adds Ann’s sister, Winkie Giddens Green (Murphy, 1958). “You’d see all your friends from school.” She pauses and giggles. “If they wanted to be seen, that is.”

In general, the people interviewed explain, those who were there to talk and pal around parked near or sat in lawn chairs by the concession stand. “But most of us went there to neck, ” laughs Abe Mitchell, a patron in the early ’50s. And that meant steering far away from the lights and the crowd.

|

WORKING ON OUR NIGHT MOVES

The back row is where an unidentified star athlete turned realtor (SATR) headed for privacy. “Twenty-seven out of the first 30 times I made love was at the drive-in, ” SATR says with authority. Although possessed with perfect recall of this almost 50-year-old personal statistic, he remembers only one scene from one movie. “I sat up once during ‘Five Easy Pieces’ because I wanted to watch the Jack Nicholson diner scene.”

“That’s the best batting average he ever had, ” says my cousin, Bryan Tallman, who knows SATR. Tallman made his own sort of “front-page drive-in news, ” as lyricist Bob Seger would put it. When courting now-wife Connie Vautier Tallman (Murphy, 1967), “I saw ‘The Graduate’ three nights in a row at the Auto Show. I was about to ship out in the Navy. There was no other place we could be alone. I still have dreams about Anne Bancroft.”

Kirksey Pritchard (Murphy, 1968) and Joe McIntosh (McGill, 1966) found themselves in the back seat on the back row during a blind date. The other couple, who was having a final date but didn’t yet know it, petted and smooched loudly in the front seat. Kirksey and Joe were too embarrassed to look forward or listen. They glued their eyes on each other and talked nonstop. They’ve been married 41 years.

An anonymous Mobilian bid farewell to maidenhood — she thinks — in a Corvette while “Rosemary’s Baby” was playing. She was so upset about what was happening — in the car, not on the screen — that she pushed the fellow onto the gearshift. The ’vette went into neutral, rolling into a car behind them. She sighs, “Do I have to count it as my first time?”

REELING IN

Drive-ins reached their peak of 4, 063 nationwide in 1958. Today, fewer than 400 are in operation; 10 or so are in Alabama. In the next few months, the studios’ final phase out of 35-millimeter film may mean curtains for mom-and-pop-run survivors, most of which can’t afford $70, 000 digital projectors.

Viewers may blame themselves – if only we hadn’t snuck in friends and food or ripped off speakers – but bottom line problems run deeper. For one, the proliferation of multiplexes have made indoor entertainment more comfortable. Who could argue against no bugs, cushy, reclining seats and better sound? And it’s easy to park at a mall, which was a benefit drive-ins used to lord over the old downtown theaters.

“Part of the collapse was due to car air-conditioning, ” Ann Green claims. In 1960, only 20 percent of all cars had a/c. In 1969, half did. People began to prefer not to perspire, but couldn’t keep their engines on through two films.

Also contributing to the demise: film choices and quality. When Hollywood began cutting back on the number of drive-in prints, movie selections were fewer and worse. People who were more interested in a good show than socializing seemed to care about that.

Another major component was the land. A tract that could accommodate 350 parked cars (Do Drive-In) or up to 900 (Auto Show) was tempting to developers. For example, the Auto Show’s lot on U.S. Highway 90 and Azalea Road is now a shopping center.

“It was painful to see drive-ins struggle, ” says Ed Campbell (Murphy, 1962), a loyal Friday night patron in the early ’60s. “They tried very hard to stay afloat.”

“By mid-’70s, owners were squeezing out every penny, ” Culbreth says. “They made you open the trunk as soon as you drove in. No ice chests allowed. No food.

Once, they confiscated the pizza we were hiding under a blanket.” Too little, too late. Selling pizza wasn’t going to make up for amenities at modern theaters, not to mention competition at home from color TV, cable, VCRs and movie rentals. Throw in bad weather and daylight saving time, which cut into viewable hours, and drive-ins were a done deal. Lights went out on a beacon of fun and freedom. But, oh, how the memories linger.

|

THE WORST OF THE WORST MOVIES

Drive-ins started out with A-list movies, starring Ava Gardner, Frank Sinatra, Jerry Lewis, Dean Martin, Esther Williams, Ginger Rogers, John Wayne and other big names. But over time, casting, plots and production values deteriorated. Honk your horn if you’ve seen any of these flicks:

“Poor White Trash” (1961)

Mobilian Myer (Mike) Ripps bought back from the studios a dog of a film,

“Bayou, ” which had first been produced in 1957. He added a three-minute scene of a girl running seminude through a swamp and rolling in mud, then slapped on a new title, “Poor White Trash.” Ripps’ remake used terrible stand-ins for the stars, according to critics, but his promo of the low-budget film was a stroke of genius. He claimed that armed guards would be at movie entrances to verify that viewers were over 18, which certainly aroused interest. “Trash” grossed more on opening day than “Ben-Hur” and earned an estimated $10 million.

“Macumba Love” (1960)

Ripps, who owned Prichard’s Do Drive-In, explained how he became a producer to June Wilkinson, star of another one of his exploitation films “Macumba Love.” “Well, I may not be able to do much better than these movies they keep giving me to show in my theater, but I can’t do worse.” “Macumba Love, ” described as “more ridiculous than scary” in its portrayal of voodoo rites, torture and deadly snakes, earned $3 million.

“The Horror of Party Beach” (1964)

Combining the beach blanket, horror and sci-fi genres, the hybrid storyline spins around mutant sea monsters attacking young women at slumber parties on a beach. Women keep going to the slumber parties “even after a few murders.”

“The Creeping Terror” (1964)

One of the worst horror movies ever made, according to critic Anna Marie Bowman. The dialogue and visuals are out of synch, and “the monster looks something like a carpet-covered version of a Chinese dragon.”

“Santa Claus Conquers the Martians” (1964)

In my opinion, the title kind of spoils the ending. Anyway, parents on the Red Planet abduct Old Saint Nick to keep their little ones happy.

“Night of the Lepus” (1972)

Giant bunny rabbits become rampaging killers. Janet Leigh (“Psycho”) and cowboy favorite Rory Calhoun star in this Easter-gone-awry romp.

“Attack of the Killer Tomatoes” (1978)

Do I need to spell it out?

Blink your lights if we missed your favorite drive-in movie,

and tell us about your experiences.

Text by Judy Culbreth