|

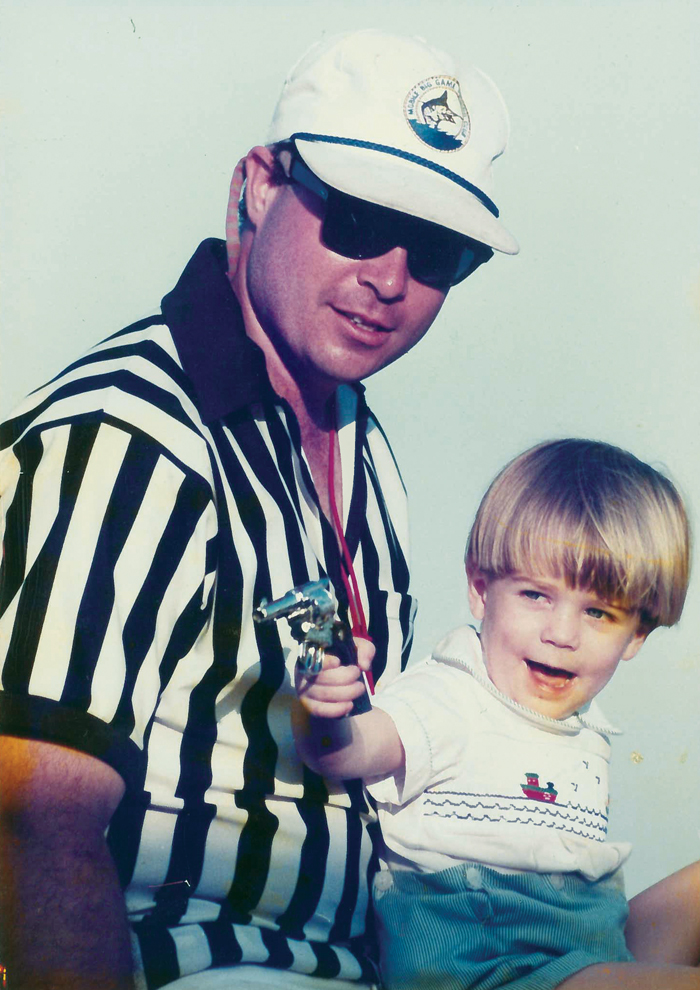

Herndon Radcliff has been in the saddle for as long as he can remember. Before Herndon could even manage the reins himself, his father, Bobby, carried him in the saddle while umpiring matches at the Point Clear Polo Club. Herndon remembers the excitement as the mare they rode stopped short and turned quickly, leaving him feeling as though he was going to fall, and then the exhilaration when she took off running again.

With three generations of polo players in his family, Herndon was destined to pick up a mallet at some point. They say once you hit that little white ball, you’ll be chasing it for the rest of your life. But not even Herndon’s family imagined he would turn the pastime into a professional career.

Point Clear Polo Club prides itself on having a grassroots, family atmosphere. The “sport of kings” takes a decidedly laid-back air on the Eastern Shore, where experienced players love introducing the sport to newcomers, loaning horses, sharing grooms and welcoming anyone with an interest. In this familial atmosphere, Herndon, then 13 years old, joined the United States Polo Association with a handicap of minus 2 (the lowest given), playing with two hand-me-down horses and borrowing a third when he could. He had to ride each horse twice per game to fill the 6 chukkers (polo speak for period or inning) and learn the rules of the sport as he went along. Herndon says that, while his dad introduced him to polo, he never really gave Herndon any formal lessons. “He just threw me on the back of a horse and let me get out there.” It was not until several years later when Herndon began to tag along with Gonzalo de la Fuente, a professional player who came to work in Point Clear, that he started to take it all seriously.

Gonzalo had a handicap of 4 and was one of the better players to spend time in Point Clear. Before long, Herndon was spending his spring breaks exercising horses with Gonzalo and refining his game instead of hanging at the beach with friends. He headed to the University of Kentucky to study equine science and, while there, began retraining young thoroughbreds off the track to play polo. He sold a few for a profit, bought some more horses, did it again. He developed his own string of ponies, played on Kentucky’s polo team and refined his game even more. But in his senior year, with only three credits left until graduation, Herndon made a bold move. He left school and took a job as a groom’s assistant — that’s right, the bottom of the totem pole — in Argentina. As an ayudante, or “helper, ” Herndon learned more than any schooling could have taught. What baseball is to America, polo is to Argentina. Time spent in a place where people live, eat and breathe polo exposed him to world-class players, gave him the opportunity to ride first-rate horses and was critical to taking his game to the next level.

|

Since then, Herndon has worked his way up in the sport, playing on various teams across numerous states, improving his swing, training new horses and making contacts. The U.S. Polo Association rated him with a handicap of 2 (on a scale of minus 2 to 10), and Herndon made the U.S. team this past spring at a qualifier in Australia. The World Cup Tournament was in his sights, and he was planning a trip to Sydney this October to represent the United States. Then something funny happened that you would never see in any other sport. Herndon had a phenomenal year, and when the USPA updated player handicaps in June, his rating was increased from a 2 to a 3. He was moving in a good direction. But that one point increase in his handicap bumped him from the U.S. team.

To understand how becoming a better player can kick you out of one of the most prestigious tournaments in the world, you have to understand how polo works. Each player gets a handicap from the USPA that is reevaluated each year. Every tournament has a set goal, which is the combined handicap of all four players on a team. At small clubs like Point Clear Polo, teams can start with a point on the board to offset any imbalance between two teams. But at the World Cup, which is a 14-goal tournament, the players’ handicaps must evenly add up to 14. No more, no less. Herndon’s extra point put the team over, and so he was passed over for an alternate with a 2 rating. And so he will sit home this October.

While Herndon admits the decision was a setback, his polo career is impressive even without a World Cup under his belt. No backyard nags anymore, no racetrack rejects. These days he rides an impressive string of 12 horses, most of which he owns, but a few are sent to him for training. He has his own groom and takes his sport as seriously as any professional athlete. “The horses need to be fed and cared for year-round, so as a professional, you need to be playing year-round to make enough money. But that takes a toll on your body. The best players these days have trainers, physiotherapists, they are drinking recovery drinks and working out. They take it as seriously as the NFL or the Major Leagues.”

But unlike professional baseball, he points out, you will never see a team owner on the field throwing a pitch. That’s where polo differs from other professional sports. In most matches, the owner of the team is out there playing with the pros, so long as their handicaps all add up right. Men and women of all ages and abilities might find themselves on one team, and in this way, the “sport of kings” can be extremely democratic. There are a handful of players in the world with a handicap of 10, but most professionals fall into Herndon’s handicap range. And the good news is he has decades left for improvement. Polo players often perform well into their 60s.

Herndon is heading to Argentina this fall to help find new horses for the head of his team, and while there, he plans to get another taste of high goal polo. He is focused on the matches in front of him but, undoubtedly, with one eye on that next World Cup qualifier.

ABOVE Radcliff, pictured third from right, made the United States’ starting team for the Federation of International Polo’s World Cup Championship. He was later replaced by an alternate in the lead-up to the October 2017 match in Sydney, Australia.

What you need to know

- Most polo matches consist of 6 chukkars (periods) of 7 minutes and 30 seconds each, with a 10-minute halftime. Smaller games can be played as a round-robin, where 3 teams play each other 3 chukkars.

- Safety Equipment: Players are required to wear a protective helmet secured by a chinstrap. Some helmets have an added facemask, but many professionals forgo this measure, citing it limits vision. Players also wear padded leather knee pads. These days, most players wear shatterproof protective eyewear.

- A polo ball is typically about the size of a baseball and made of hard plastic. It weighs about 4 ounces. The mallet is 48 to 54 inches long, depending on the height of the pony and the reach of the player. The shaft is made of bamboo, the grip is similar to a tennis racquet’s and the head is typically made of ashwood or maple.

- Players are rated on a scale of -2 to 10, which is determined by a player’s horsemanship, hitting ability, quality of horses, team play and game sense. The team handicap is the sum of its players’ handicaps.

- Players must carry the mallet in their right hand. Playing left-handed was banned from polo in the mid-1930s for safety reasons.

- Men and women of all ages are allowed to compete with each other since both sexes are rated on the same handicap scale.

You can find more info about rules, local clubs, and tournaments going on around the country at uspolo.org. If you want to watch a local match or get in the saddle yourself, visit pointclearpolo.com.