In 1925, 67-year-old Henry James Stuart climbed down the steep bluffs of the eastern shore of Mobile Bay and began gathering bricks from the beach. They were the remains of brick-making factories that had operated along those shores over 100 years before. He bundled the bricks, along with white beach sand, into sacks and piled them onto his back. He then climbed, barefoot, back up the slopes of the bluff and carried the cargo a half mile through the woods. With these materials, he began to build a house in Montrose, Alabama, we now know as the round house of Tolstoy Park.

As its name suggests, the single-story house is round. It is only about 14 feet in diameter and height and has a domed roof. The property it stands on was once 10 acres of mostly pine forest, neighbored by a few other distant houses on even larger acreages of property. Stuart named his land Tolstoy Park in honor of the writer, Leo Tolstoy, who he felt a kinship toward. Other than a layer made from the old bricks picked up from the beach, the house is built of cement blocks. Each one was individually poured by Stuart himself and etched with the date of its creation. The inside and outside of the house were covered in plaster made from the sand Stuart collected on the beach and from a nearby creek. Outside of his home, Stuart built rows of cement garden beds, where he grew most of his food, and a few cement sun dials.

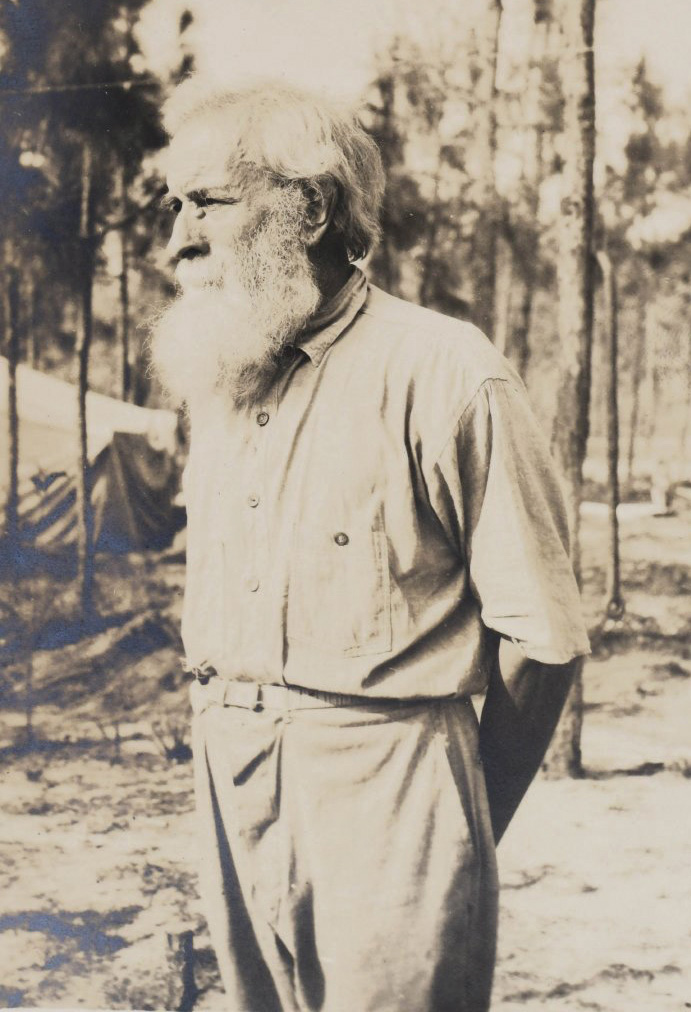

In 1926, the house was completed, and Stuart’s visitors nicknamed him the sage of Montrose, the hermit, and the modern Thoreau. He became a notable character locally in his own time and remains notable today. Part of his fame is due to his round house, which still stands today. The other part is due to his character. Stuart let his white hair and beard grow long, wore baggy old clothes, and didn’t wear shoes. For money he weaved rags and rugs on a loom and sold them to tourists and visitors. He was a vegetarian and an anarchist, once sending a letter and woven rug to the famed anarchist Emma Goldman while she was in prison.

The romanticization of Stuart’s life, and especially the comparison of his lifestyle to ours today, often leads to the belief that he lived without the comforts or advantages of his time. True, Stuart wanted to live a simple, Thoreau-esque, life. But compared to anyone else living in a rural patch of Baldwin County during the time Stuart lived there, between 1923 and 1944, his comfort level was actually above average.

Before the completion of the round house, Stuart lived in a cabin at Tolstoy Park made from wood and sheets of metal. Photographs taken on the inside of the cabin are very brightly lit, almost harshly, from above. There were no skylights on the roof and gas lamps would not have created the lighting seen in the photographs. What appears to be power lines can be seen attached to the side of the cabin and we can deduce that Stuart was using electric light bulbs. Photographs of the round house seem to show power lines attached to that as well. A rusted old power junction box can still be seen inside the round house today.

This may surprise us, because we equate simplicity and hermitages with an electricity-free life. The real surprise, though, should be that Stuart even had the option of electric power. Electric power was expected, at that time, in urban areas, but not in rural ones. For comparison, as late as 1935 only four percent of Alabama farms were receiving power line electrical service. Stuart’s remote home in the woods happened to be close enough to the city centers of Fairhope and Daphne, and close enough to the blufftop resorts of Montrose, to be near power lines he could take advantage of. Photographs of other nearby cabins and homes show us that neighbors in the area, though near the same power lines, were not using them.

Like his neighbors, though, Stuart was not connected to any municipal water lines. Photographs of Stuart’s property show, and entries in his journal mention, a water well on his land. Later, his journal entries say that he retrieved water from the property of his neighbor, Prescott A. Parker. Stuart would have to pump, lift, and carry home any water that he wanted to use. While this seems severe from a modern perspective, it would have been entirely unremarkable then.

Advertisements in the Fairhope Courier from the 1920s, listing homes for sale and rent within the city, specifically mention they include city water. This illustrates how, even in urban centers, access to municipal water lines was not a given. In rural areas, municipal water lines would have been as rare, or more, than electrical lines. Courier advertisements from the 1930s, for example, list farms for sale, just outside the city limits, with their own private wells. In fact, 20 percent of Alabama residents today still use private well water.

Stuart wasn’t just comfortable, though, he even owned a luxury of his time— a high-quality typewriter. Stuart wrote extensively, both in letters to friends and in articles to magazines. Trained in telegraphy as a young man, Stuart was likely a practiced typist, and a typewriter could have been a quicker method of writing for him than handwriting. A picture of Stuart, seated at a concrete table, the typewriter in front of him, shows us the brand of typewriter he used was an Underwood. Underwoods were popular, eventually selling millions of machines, and used by Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and William Faulkner.

The average price of a typewriter in the 1920s, though, was around $100, which, adjusted for inflation, would be the equivalent of around $1,800 today. Ads in the Fairhope Courier for used typewriters in the 1920s show the price being as low as $36, which would still be around $670 today. On top of that would be the cost of upkeep and replacing the ink ribbon. Due to the high cost of the machine, and because it would not be used much on average, home typewriters were uncommon until the early or mid-1930s. Even then, only writers or professionals who would continue working at home after office hours would bother owning one.

For every aspect of his life, we find that Stuart lived, at worst, as ordinary and comfortably as his neighbors. Usually, he lived more comfortably than them. Even working as hard as he did, as far into old age, was typical in a time before retirement became widespread. Walking barefoot and without a hat, as he was famous for doing, was eccentric but not ascetic. And while he chose to live off the land as part of his philosophy of life, the ability to do so would have been a god-sent opportunity to millions of city dwellers during the Great Depression from 1929 to 1939.

Our instinct, though, is to admire this man, his home, and his way of life as something exceptional. And our instinct isn’t wrong, but when we look at these parts of his life, we are just seeing one side of the coin. Stuart did not live an unachievable lifestyle, devoid of luxuries and comforts. He was not isolated, and he did not try to obtain a far-off connection with nature and a higher spirituality like a monk on a mountain. He was, remarkably, an ordinary man.

In 2020, descendants of Stuart brought to the Fairhope Museum of History three journals that he had kept while living at Tolstoy Park. And in them, for every day of the year, a near-hourly schedule was written. He noted the weather, the time he would wake up, what and when he ate, and if he read, wrote, walked to town, or had visitors. There is no poetry, essay, reminiscence, or philosophy to be found.

But at least one contemporary friend of Stuart’s had seen the other side of the coin in this. In 1979, seventy-seven-year-old Converse Harwell, who had been a friend and frequent visitor of Stuart, wrote in his column for the Fairhope Courier: “[Stuart] told what he did hourly and why, not as an idle boast but to illustrate the simplicity of his daily life, the art of living hour by hour…”

What Harwell was describing is the practice of mindfulness: an awareness of the present moment and one’s own thoughts, feelings, and sensory perceptions in that moment. Practitioners describe it as truly living in the moment by being intentionally present, and not just going through the motions of everyday life while being mentally elsewhere. It was not what Stuart did or how he lived that was unique but that he did so with a mindful intention. He did not just live a simple life, like the author Henry David Thoreau, he was the embodiment of Thoreau’s words: “You must live in the present, launch yourself on every wave, find your eternity in each moment.” He was free of thoughts about the past and future and remained grounded in the present by focusing his attention on simple things as they occurred: the weather, the hour he woke up, what and when he ate. He was mindful of the shuttle of his loom as it passed through the threads of his rugs.

Today, books, retreats, lectures, and all else mindfulness is estimated to be at least a billion-dollar industry. This is probably good news in a time when the digital world has eroded our attention spans to dangerously low levels. On top of that, the mass spread of information, much of which is untrue, has led to an increase in collective anxiety about the future. Phones, apps, and social media aren’t solely to blame, though. We’re flooded, even in the non-digital world, with cheap throw away products we don’t have to put any real thought into. A thousand different hobbies can start and end at Walmart because they are so cheap there’s no need for real commitment.

Mindfulness doesn’t have to be found at the peak of a mountain, though, or in a cave. Stuart found it in Montrose, Alabama. He had electric power, work, hobbies and a typewriter he used to communicate across the country. He read newspapers, magazines, and letters from across the country, too. But he remained in the present. And when his mind wandered, he could find it again in ordinary tasks.

Stuart’s legacy is showing us that no matter what the time or place, or the technology available, we can be mindful. Anyone who has tried to be mindful, though, even for just a minute, knows that it is easier said than done. Fortunately, Stuart left us with some help — the round house. Visitors to the house today are still greeted with calm and quiet. The temperature inside is always comfortable, thanks to its insulating walls sunk nearly two feet deep into the ground. But most importantly, when visitors look around the inside of the house, they can still see the dates etched into the cement blocks marking the day of their creation. In this we see every moment Stuart spent on them, intentionally, block by block. And we remember to live hour by hour.