In a world where carbs are increasingly shunned, people might think that the sweet potato would be particularly unhealthy. After all, the words “sweet” and “potato” hardly sound like markers of health. However, this assumption couldn’t be further from the truth. The sweet potato is only distantly related to russet potatoes and is a part of the morning glory family (they share a similar root structure). Orange sweet potatoes are high in the antioxidant beta carotene, which increases vitamin A levels in the blood. They are packed with B vitamins, potassium and vitamin C. Sweet potatoes are known to be high in fiber and have a low glycemic index, which results in a less immediate impact on blood glucose levels than a typical potato or starchy side dish. Given the fact that sweet potatoes are healthy and easy to grow, they have been a source of sustenance in the United States for hundreds of years. Natives cultivated sweet potatoes in the Southern United States and Christopher Columbus brought them back with him on his return trip to Spain. Enslaved Africans also played a role in the proliferation of sweet potatoes in the U.S.

History | DEEP ROOTS

Sweet potatoes are native to Central and South America and were first brought to Europe by Christopher Columbus in the 15th Century. They were cultivated by Native Americans prior to European arrival and bear a close resemblance to the African yam. A longtime staple of the West African diet, yams were easy to grow and naturally pest resistant, provided high yields and essential nutrients, and were consumed in a multitude of ways, including fresh, boiled, baked, cooked in ashes, dried and powdered. Critical to survival for many, the yam is still revered at harvest festivals, called Yam feast days, throughout West Africa. A symbol of rebirth and renewal, yams are at the center of extensive mythology and often accompany ceremonies relating to birth, marriage, recovery from sickness or injury, and death.

When West Africans arrived as enslaved people in America, they applied their knowledge and experience cooking with yams to the American sweet potato, which quickly became a cornerstone of the Southern diet for all classes. Resembling the yam’s role in West Africa, sweet potatoes shielded Southerners against hunger during lean times and were especially vital for poor populations as they grow easily, produce abundantly (often with little human help), can be preserved through the winter in a mound of dirt and, when paired with greens, provide nearly all essential nutrients.

The centrality of sweet potatoes in the Southern diet made sweet potato pie a core Southern tradition beginning in colonial days, when pies both stretched ingredients and turned humble meals elegant. Europeans, who had consumed pies since the Roman era, made pies in America using apples, lemons, plums and sweet potatoes by the late 1600s. Enslaved people from West Africa, who did the cooking in many colonial households, shaped sweet potato pie by experimenting with spices, techniques and various ingredients, adding cinnamon, nutmeg, vanilla, cloves, ginger, molasses, orange zest and coconut to the basic pie filling. Because pigs were abundant in the South, cooks used lard instead of butter in their pie crusts, giving them “a distinct, flaky quality.”

In the early decades of the twentieth century, George Washington Carver helped secure the longevity of sweet potato pie in Alabama. As the head of the agricultural department at Tuskegee Institute, Carver encouraged farmers to plant crops that would replenish the parched Alabama soil, including sweet potatoes. To spread his message, he produced scores of farming bulletins that were practical, free and comprehensible. Between 1898 and 1943, Carver issued nearly 50 bulletins on sweet potatoes alone, featuring the 118 products he invented from the sweet potato (including molasses, vinegar and shoe blacking) as well as various sweet potato recipes. His recipe for sweet potato pie, published in 1936, is a prototype of modern versions.

In the 20th century, sweet potato pie became elemental to soul food. In reality, the dishes that comprise soul food are Southern dishes, consumed by Black and white alike for centuries. As culinary historian Frederick Douglass Opie notes, whether Black or white, “every poor person struggling to survive [in the South] ate soul food on a regular basis.” But though the actual dishes may be identical, soul food separates itself from Southern food by underscoring its African American qualities. Black cooks were largely the ones to fuse African, Native and European traditions to create Southern food. Soul encompasses the ability of these cooks to transform ordinary ingredients, use whatever was at hand, follow the seasons and spice to perfection. Soul emphasizes the African cooking techniques, food pairings and seasonings that define Southern food. “It was simple food,” writes Opie, but “complex in its preparation.” And at the end of the meal, that last dish manages to roll all of those conflicting characteristics of soul – sweet, savory, complicated, straightforward, tenacious, joyful, sustaining, luxurious – into one: sweet potato pie.

TEXT BY EMILY BLEJWAS: Adapted from “The Story of Alabama in Fourteen Foods”

Bottom-right Photo by Matthew Coughlin

Farming | INNOVATION

Third generation farmer Daniel Penry can link a lot of their farm’s innovation back to the year 2000. That’s the year no one wanted his family’s sweet potato crop. “It all went to canning that year,” he explains, which pays pennies on the dollar compared to the fresh market. The reason being they weren’t curing their product — a process where potatoes are stored in wooden crates with the right airflow and sometimes air conditioning, causing the skin to dry and tighten and the potato to lose up to 4% of its weight. None of the big buyers wanted green potatoes and the Penrys were left out in the cold. He says that after 2000, the family was ready to invest in the future.

The following year they built big open sheds with huge fans to circulate the air. As the years went on, they added walls, then insulation. These days, the farm employs a high-tech computerized ventilation system that can produce 2CFM of air movement per bushel. With 15,000 bushels per building, Penry says it will blow the hat right off your head.

It was a huge capital investment, along with the purchase of all the wooden crates that hold those potatoes while they’re curing. But it was a make-or-break moment for the Penrys. Now, those cured potatoes are a product that can compete with the well-known North Carolina, Louisiana and Mississippi sweet potatoes.

Large innovations may keep a product relevant in the marketplace, but small tweaks on the farm can have a big impact on an operation, as well. While they say necessity is the mother of invention, you’ve got to have some skills, too. It’s a good thing second generation farmer Steve Penry has skills in spades. He can weld, knows plumbing, electrical, hydraulics. Those may be fairly common skills for a farmer to have, but he was also blessed with an inventor’s brain. When something wasn’t working on their 300-acre sweet potato farm in rural Daphne, he would find a solution.

“My dad invented the vine cutter,” declares Daniel, the current farmer under the Penry name on County Road 54. “Once the foundation crop was out there growing, we had to go out in the field with butcher knives and cut the vines by hand.” It was slow, back breaking work. The elder Penry invented a machine that moved down the rows with blades on each side. It would swiftly cut the vines, scoop them up, bring the tiny plants up a chain and load them in a wagon. Just two workers could cut all the vines in no time.

He also invented a self-bailing dump tank that saved the Penry men hours each week being elbow deep in mud, as well as a mechanism to lift and remove plastic sheeting off the plant beds each week for watering and spraying. Before this invention? One man could work one quarter mile row and back in a morning, pulling the plastic up by hand. “We did it that way forever,” Penry remembers. “Now he and I can go pull all the plastic on the farm in about an hour because he invented this thing.” Somebody would have been pulling plastic somewhere on the farm pretty much all the time without it.

While the Penry’s useful inventions save much hard labor for the father and son duo, there are still so many large and small places for innovation on a sweet potato operation. Unfortunately, Daniel has had to figure most of it out by trial and error. “I have to do my own research because all the official research is done in North Carolina where they have a really tight soil — a fine sand — and chemicals can’t permeate that ground. They have a white clay in Mississippi, and clay in Louisiana, too. But our dirt is like coffee grounds, so whatever you put in will go straight down to the potato and will mess it up.” And growing a good-looking potato is important to Penry.

“I moved away from certain herbicides that work really, really well because they affected the shape of our potato. Sure, it may kill all the weeds, but if you get the right rain after you use it, it will make those potatoes round.” It isn’t written down in a sweet potato lexicon somewhere, but Penry knows it to be true from experience. “My goal is to make a long, pretty sweet potato. You see those round North Carolina potatoes? Nobody wants a sweet potato ball. You can’t cook it, you can’t cut it, they don’t look right. And that herbicide will make it into a softball. But that’s how I sell my potatoes — I make them pretty.”

He laughs that a lot of his discoveries have come by accident, and he quickly calls his friend Dr. Mike Cannon, retired head of the Chase Louisiana Research Center at LSU. “He’s kind of ‘The Guy.’ We kick around ideas about fertility.” Once Penry called Cannon about a field full of vines but no potatoes. “He says go out there with a mower and give them a haircut and see if that stimulates the potatoes to grow.” Penry says it worked like a charm. A military-style buzz cut let air get to the ground, which allowed more sunlight. The soil warmed and the potatoes grew.

Another time his field workers called him over with excitement as they harvested a few rows that had quadruple the normal yield, wondering what had made the difference. “Turns out back in January I was fertilizing my nearby plant beds, and I overdid it by about an acre. Then we planted that acre like everything else and never thought about it again.” The acre that got the early January fertilizer produced two trailer loads of potatoes every pass down a row, whereas the normal fields would yield one trailer load per round. “I think it had more to do with timing than the quantity of fertilizer, but it is something we are experimenting with.”

Experimenting seems to be the key, along with a willingness to try new things. But Penry says sometimes old-fashioned methods are the best. In the interest of using as few chemicals as possible, he attacks weeds and bugs in other ways whenever possible. “We can essentially use tillage as a herbicide,” he explains. By running a deep plough, lifting a big patch of dirt and flipping it, the weeds and bugs all get buried deep under the soil and die.

“And, of course, we hand pull weeds all summer long. Even if we wanted to spray more, our plants are not Round-up ready like some crops. There is no genetically modified sweet potato. No one would eat it.”

But the ground does get a hit of fumigant early on, before the potatoes are planted. “We put the fumigant down deep and then seal it up. We till the ground, and then a big roller makes a crust, kind of like a creme brulee. That crust will keep the fumigant in long enough for it do what it’s supposed to do.” He says that growing certified organic is not an option in Baldwin County because the bugs would tote off the crop. “But by using the fumigant instead of residual pesticides, we are able to do it a lot cleaner. We put it in, it does its job and then it’s gone. It doesn’t hang out and get in the potatoes.”

All of his fertilizers and pesticides are closely monitored by his largest customer, Lam and Wesson, who buys potatoes to make products for the restaurant and grocery industry. (Penry’s roots are often sold as sweet potato fries under the Alexia name.) He knows what each customer is looking for, and he adjusts his methods to suit their needs.

“The Covington variety works well down here,” he says. “They have a thick skin and they don’t rot in the field. They can swim a little bit better than some.” A trait that is needed after summers like 2022, when Penry says it rained every day from June 15. “Most of our early crop rotted away. The vines are steady trying to make, so we were waiting for the smaller stuff to size up. Well, when it quit raining, it didn’t rain again until Christmas! We had a frost in mid-October — the earliest frost since 1990. So it was a perfect storm last year of just not making any money for me!” He manages a laugh.

“Baldwin county is a dice roll with the weather. We don’t plant more than we can afford to lose. July and august can really rain you to death. Dry years will hurt you, but wet years will take you out.” – Daniel Penry

Fortunately, they’ve had some good years, too. When things are good, the Bayou Belle is by far been their top tonnage potato. “We get paid by the pound, and they don’t care what it looks like. I am contracted and I have to deliver 4.5 million pounds this year.”

The most important thing the Penrys have fine-tuned is their timing. They follow a planting schedule that means their potatoes will be the first to market each year. Florida and south Georgia never recovered from the weevils of the 1980s, and so Baldwin County farmers were left as the southern-most sweet potato growers in the nation. “When the world runs out of sweet potatoes, we are the first to supply them. My customers expect me to have potatoes in August because they don’t.”

Knowing that the sweet potato is the official vegetable for the State of Alabama, you might wonder why it is mostly grown in Baldwin County and Cullman, where they hold an annual Sweet Tater festival each Labor Day. The answer may go back to one little crop duster in Loxley.

When the sweet potato weevil was decimating the crop nationwide during the 1980s, the root vegetable was banned in a lot of states and the crops were destroyed to prevent further spread of the pest. Baldwin County, however, got green tagged. “Another local farmer named Nick Perturis could crop dust, so he and my grandfather banded together and convinced the state to give them a shot,” says Penry. The men vowed to spray every 14 days for weevils. They brought pheromone traps to the fields, and as long as they didn’t find weevils in the area, the farmers would get the green tag and could continue to ship all over country and into Canada. “We got grandfathered in, and now it’s too late for surrounding areas like Mobile to catch up. We’ve been at it 70 years and we’re still investing in infrastructure.”

Those costs are prohibitive to a startup, he explains. “You’ve got to build a packing line, have housing for your people, you’ve got to find people! You need housing for your potatoes, boxes to put them in. So much of our equipment is specially made, or we made it.” It’s just not an easy crop to get into if you haven’t been at it for as long as families like the Penrys.

The sweet potato pie, he explains, has already been cut up.

TEXT BY MAGGIE LACY

Workforce | MARIANA

When I ask Mariana what is hardest about picking sweet potatoes in Baldwin County for a living, she just blinks. “It’s all hard,” she says. “It’s work. But it’s okay, job is job.” Mariana works nine hours a day in the fields, planting, laying down plastic or picking it up, harvesting or sorting or packing. The hottest summer months are spent “cleaning the plants” (pulling weeds) which begins at 5:30 a.m. to take advantage of cooler hours. She is the only woman, because the labor is so physical, hot and demanding.

But despite the sun, the bugs, the back and leg pain from constantly bending over, the mud and the snakes (she kills them often…with a hoe), Mariana says, “I like everything,” meaning she is grateful for this job. She has worked for the same family for years, and calls them angels. They employ her year round, supplementing the fieldwork with cleaning and painting tasks. It’s a godsend for Mariana, who used to cobble together various jobs, which were sporadic and located all over the county, while balancing child care and transportation. When she first started working in Alabama, she earned $7 an hour, just enough “to pay the babysitter.”

But she just kept going. A devout Catholic, Mariana prayed every day for help and strength. I ask when she prays, like when she first wakes up or when she gets to the fields, and she smiles. “All the time,” she says. “For everything.”

In 2006, in Michoacán, Mexico, Mariana had left her abusive husband and was working all kinds of jobs to support her 3-year-old son and 1-year-old daughter. She labored in the fields, harvesting corn and wheat, cleaned houses and laundered clothes on a washboard. “In Mexico everything is hard,” she says. “In Mexico, your hands are your washing machine.”

Even so, she struggled to put food on the table. Plus, her daughter had asthma and the Mexican air was smoggy and punishing. Mariana couldn’t afford the hospital or the medicine. Her grandmother taught Mariana how to find the right plants in the wild and brew tea to ease the symptoms, so she boiled huge batches and draped a sheet around herself and her daughter to capture the steam. “This is our house!” she told her daughter, making a game of it.

But it wasn’t enough and never would be. Wages were so low that even working multiple jobs, Mariana couldn’t provide and her daughter stayed sick. “There was no choice for me,” she says. So she scrimped and saved for eight months to pay a coyote $9,000 to bring the three of them to the U.S. They crossed the Rio Grande before dawn in an inflatable raft, with Mariana holding her daughter in her arms and her son on her back. There were 15 people in the raft, all told not to move, for fear of unbalancing and overturning it. So Mariana prayed her two toddlers would stay still. They did. They made it.

But across the border a gas station attendant reported them to immigration and they were picked up and returned to Mexico. The next day they tried again, this time passing by unnoticed, though Mariana took a bad fall that smashed both of her knees, so she arrived hobbling. The following month brought a period of waiting and traveling, including a week where Mariana walked through the Texas wilderness hearing wolves, scavenging for food and drinking any groundwater she could find. Eventually she and her children (who took a different route) reunited in Houston, where Mariana’s brother picked them up and brought them to Alabama.

Mariana’s faith and deep connection to her Mexican heritage have sustained her over the years in Alabama. She cooks the foods, embroiders the gabanes and dances the steps traditional to her home country. She keeps an altar for her parents, bakes Rosca de Reyes on Three Kings Day, teaches her daughter to make birria, carnitas and mole, and celebrates la Dia de la Virgen de Guadalupe and Mexican weddings amid a vibrant immigrant community centered around St. Patrick’s Parish in Robertsdale.

But though she’s rooted in Alabama and knows she won’t live again in Mexico, Mariana keeps a foot in both places. Of the 10 children in her family, half live in Alabama and half in Mexico, so on holidays, they celebrate identically in two countries. These mirror rites are particularly poignant during the nine days spent honoring Mariana’s deceased mother and father each year. The Alabama family gathers at Mariana’s to prepare albondigas, atole and tamales, stack massive piles of fresh fruit in offering and recite prayers alongside the priest. At the same moments at her sister’s home in Mexico, the family lays out the same foods in the same pattern, lights the same candles, whispers the same prayers. And in both places, the community lends support. “It’s the costumbre of my country,” Mariana explains. “Everybody help for everything.”

Though she misses the life and culture of Mexico, Mariana knows the economics made it impossible for her to stay. She regards her life with clear eyes, without sorrow or pity or regret. Her stories often end in a quiet, twinkling laugh. In May, her daughter graduated from high school, and her son, age 20, works for a contractor, building houses. Mariana is incredibly proud. They are the reason she came, and they are healthy and happy. Still, her life is not easy. Fieldwork is difficult and there are plenty of days when it rains and she has to hustle to make up lost wages, selling batches of tamales to Mexican construction workers on lunch break, or wheedling her way onto construction teams for the day.

Even so, when Mariana shows me photos and videos of her life, I am struck most of all by the color. The dishes and dresses and flags and music and flowers, even the tractor rolling through green fields and red dirt under blue sky, all of it bursts with the life she fought to create. Like a bright orange sweet potato, grown in Baldwin County and made even sweeter with panela, which you can only find at the Mexican grocery.

TEXT BY EMILY BLEJWAS

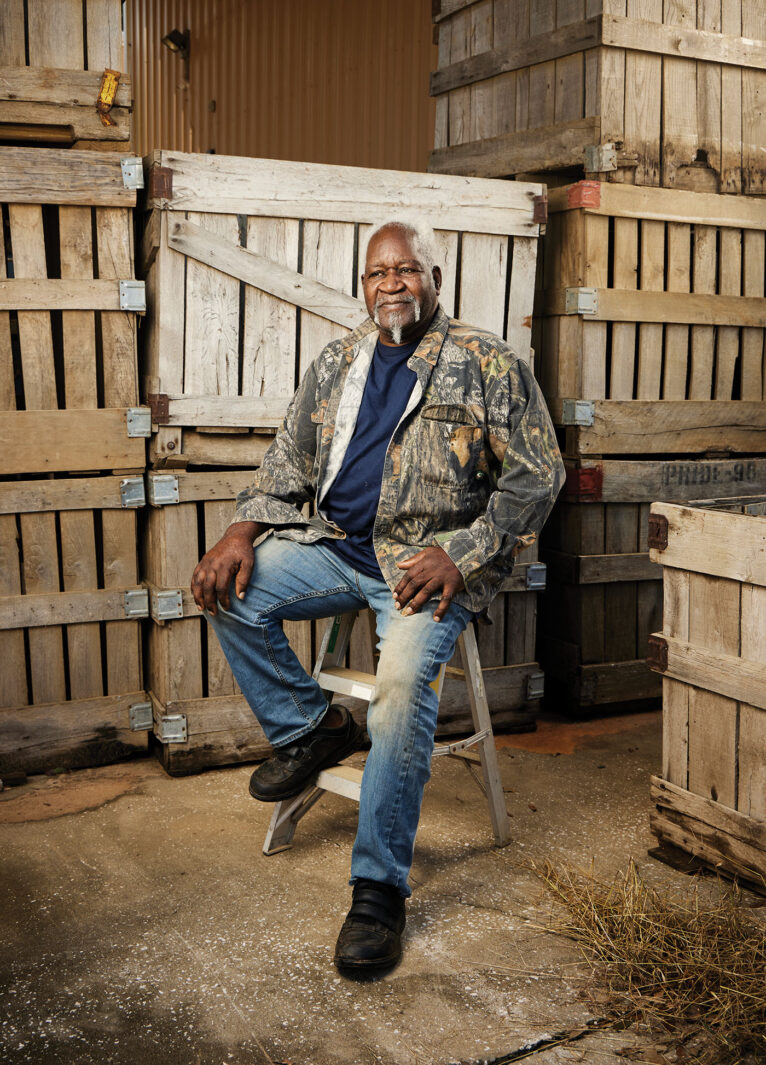

Legacy | WILLIE YOUNG

Seventy-eight-year-old Willie Young drives his pickup truck over gentle rolling hills, past bright green fields of sweet potato leaves and turns onto the long driveway leading up to farm office. He drives past stacked crates for storing sweet potatoes come harvest time, a large barn and farm equipment. He parks under the big oak trees that shade the parking lot and slowly gets out of the pickup, his Vietnam veteran hat sitting on the dashboard. Getting out of the truck takes extra time these days. “My equilibrium ain’t what it used to be” he admits, as he climbs the stairs one at a time. Inside the office door, Young sits down at the table and begins to share his story.

He goes back to the beginning, when the sun had not yet made its way over the horizon, and 5-year-old Willie would peer out from the darkness of the bedroom through a tiny crack in the doorway. It was the early 1950s and Willie’s family had moved into his grandmother’s house on Pollard Road in Daphne where they worked for Brantley Farms. He watched his mother making biscuits and cooking fatback, the scent filling the kitchen and stirring rumblings in his stomach. He watched his parents fill lard tins— “I still remember one was yellow with pigs on it, and the other was blue with mountains” — with leftover biscuits or with sandwiches wrapped in paper bags and head out the door, making their way up the road. “My grandmother said I was always into everything, and I was gon’ do what I was gon’ do.” So, it comes as no surprise that curiosity got the better of the youngster and, one morning, he snuck out the door to see where his parents were going.

As he made his way towards the adults, who were further up the road, the neighbors’ dog, Butch, lying on the other side of the fence, caught sight of little Willie and began to bark. Not wanting to get caught, Willie took cover in a potato field. He crawled along the ground, where he made it past the dog’s line of vision and then he resumed walking. Willie took cover again when he heard his neighbor driving along the road, “He come by the house before, so I knew his truck sounds. And I hid. No one was gone catch me.” Once he saw the truck had passed, Willie wandered down to a pond, and though he was unable to see his parents, decided to cross it to try to get to the field where he believed they were working.

It was there that the neighbor, returning from getting gas, spotted Willie standing neck deep in the water. “He shouted, ‘Boy, come here!’ and waded in. He was a tall man, and he was knee deep and I was just a little ol’ short thing. He pulled me out and took off his coat and wrapped me in it. Then he put me in that truck and drove me to where my momma was,” says Young. After the neighbor explained to Willie’s mother where he had been discovered, “She gave me a whoopin’ and I tol’ her I was just trying to figure out where they was.” They drove Willie out to the sweet potato field. “I didn’t know if I was gonna get another whoopin’, but instead Momma gave me a basket. A half bushel basket. I wasn’t big enough to tote it, but I could drag it,” says Young. “She gave me what’s called a skip in the field. You stuck a stick down here and a stick at the other end, and that’s your stake. Momma said, ‘Now, you keep up with that tractor.’ I thought, ‘What you mean keep up with that tractor?’ I was just a little thing, but I did it because I didn’t want another whoopin’.”

After a day working in the field from sunup to sundown, Willie woke up hungry the next morning. He smelled sizzling bacon and his momma’s biscuits cooking in the oven. He fixed a plate and ate his fill. “I got myself up to go lay down because my belly was full. Daddy said, ‘Where you goin’, boy? You got to go with us today.’ Then he handed me one of them little tin buckets with momma’s biscuits in it — she always made the best biscuits and I carried it up the road. I had to try to keep up with them because I was slow, and my lil’ legs were runnin’. We got in the trailer and I sat in between my momma and daddy and asked, ‘What we gon’ do today?” Daddy said, ‘The same as you did yesterday. You gon’ work.’”

“And I worked ever since.”

Young worked at the farm all the way up until turning 18 in 1964. Then, seeing an opportunity to escape farm life, he caught a ride to Mobile and hopped on a bus to Montgomery. He signed up for the army and was sent to Vietnam.

Young’s parents were amongst the last of a generation of African American workers who spent their lives performing seasonal farm work. The civil rights movement allowed for more opportunities beyond such physically demanding work, and many of the children of generational farming families sought opportunities elsewhere. While Russet potatoes can be planted and harvested by machine, sweet potatoes are more delicate. The work must be done by hand and requires long hours of bending over and lifting heavy bushels of the potatoes. Today, the government’s H-2A program allows for migrant workers to obtain work as temporary agricultural workers in Alabama and across the United States. These workers are generally young men in their twenties, who unlike Willie’s parents, work for a few years in this labor-intensive work and then move onto other occupations.

After Willie Young’s military service, he returned home and was employed in demolition until 2002, when he was unable to physically continue working.

Now, he spends time with his grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren, “I have enough of ‘em to fill two Greyhound buses,” he laughs. He delivers collard greens and sweet potatoes to older people in the community who are in need. Mornings are spent at Daphne’s May Day Pier, teaching local children how to catch and clean redfish… and occasionally napping. “I like to spend time with the children. I teach them how to tie mayflies,” says the man who spent his own childhood in the fields. While his travels are limited these days, he still stops by local farms to catch up and pick up a bushel of sweet potatoes.

After reflecting on the twists and turns of his life, Young picks up a potato, fresh from the local fields, his hands still large and muscular after years of hard labor. “This really a is a fine-looking sweet potato. The best one’s got to look just right. And you see how its darker if you scratch some of the skin off with your finger? That means its sweet. You rub some bacon grease on this and put it in the oven. That’s good eatin’.”

With that, he sets the sweet potato down on the table and slowly stands up to go home. “By the way,” Young says, gesturing to a potato sack framed on the office wall, “You’d never store sweet potatoes in a sack like that. Sweet potatoes are like people. They need air.” And in his way, he slowly walks out the door.

TEXT BY MARISSA DEAL

Food | MODERN TAKE

“My earliest sweet potato memories involve a baked casserole with pecan crisp and marshmallows,” says the executive chef and owner of The Hummingbird Way, Jim Smith. “And it’s still a great holiday dish.” (In fact, Americans purchase 50 million pounds of sweet potatoes for Thanksgiving each year.) However, contemporary chefs such as Smith and Adam Stephens, executive chef of the Hope Farm, are putting modern twists on the superfood.

Stephens enjoys branching out from the ubiquitous orange sweet potato and often serves white sweet potatoes as a side, which are slightly less sweet than their orange counterparts, but still sweeter than a typical Russet potato. Stephens describes it as “an unexpected take” on a classic side dish. And for a real pop of color, one Thanksgiving Stephens used purple Okinawan sweet potatoes to create a novel version of the holiday favorite.

“I regularly cook with sweet potatoes; whether it is dried crisps for garnish, pie filling, sweet potato infused liquor or simply roasted. One of my favorites in the fall is making them into gnocchi with brown butter vinaigrette with parmesan, herbs and pecans,” says Smith. Stephens endorses the versatility of the superfood. “They can be baked, twice-baked, or spiced with chiles and roasted. I make potato cakes served with braised pork or oxtail. It’s a beautiful and simple dish.”

Sweet potatoes are being distilled into vodka — which results in a nuttier, earthier spirit with a hint of sweetness — and into moonshine. They are even making appearances in cocktails. “Sweet potatoes would make a fun clarified milk punch,” says Stephens.

Versatility has always been one of the hallmarks of the once-humble little tuber, and with America’s expanding palate for international cuisine and innovative flavors, the sweet potato is ideal for trying new preparations and culinary approaches. But at the end of the day, sweet potatoes will always be baking in Grandma’s oven on Thanksgiving, butter melting, brown sugar caramelizing. Because sweet potatoes, like many foods, are not just something we eat. Sweet potatoes are a holiday memory, a family tradition, a recipe hand-written on a weathered card — or not written anywhere because it is emblazoned in our memories from watching our mothers and our grandmothers add a dash of this and a stir of that. Sweet potatoes are a part of the tapestry of our lives.

TEXT BY MARISSA DEAL

How to grow a sweet potato

Unlike most other plants, sweet potatoes are not grown from seed. Instead, you sprout the potato itself, cut off the shoots and plant directly in soil.

For potato farmers, it all starts at the University level. According to Penry, scientists and researchers will allow a sweet potato vine to flower. A technician harvests the seeds from the flower, makes a slurry and from that slurry they make the first plant. That’s the foundation seed.

They sell those plants to seed growers who can grow that plant, and the first crop off that plant is Generation 1. “We buy truckloads of those G1 potatoes from seed growers in North Carolina,” Penry explains. “We buy some

every year to keep our seed stock fresh.” Those become the farmer’s

seed potatoes.

In February, the seed potatoes are placed in an outdoor plant bed that consists of five-foot sections covered in dirt with plastic rolled tight over the top. The plastic heats the ground up enough to make the potatoes sprout.

In April, the shoots are cut off the potato with a knife, put in a basket, loaded on a trailer and taken directly to the field. A person has to plant each plant by hand by riding through the field on the back of a tractor. The tiny plants then receive 200 gallons to the acre of water, as well as fertilizer and a microbial mix to replenish the soil. “Then it’s just grow, baby, grow!” laughs Penry. “We can plant 20 acres a day if we already have the plants cut.”

Once they’re planted the fun begins, he laughs, trying to keep the bugs, weeds and diseases away.

Potatoes will be harvested by hand from August 1 through November 1.

These potatoes, which were grown from the seed potatoes, will be called Generation 2.

Did you know?

- When West Africans arrived as enslaved people in America, they applied their knowledge and experience cooking with yams to the American sweet potato, which quickly became a cornerstone of the Southern diet for all classes.

- Unlike most other plants, sweet potatoes are not grown from seed. Instead, you sprout the potato itself, cut off the shoots and plant directly in soil.

- While sweet potatoes and yams are both tubers, the two are only remotely related. Yams are starchier and firmer, with less health benefits than sweet potatoes.

- Unwashed — or green — potatoes can keep all winter, a trick our ancestors knew well. Dirt keeps the potato peel dry and intact, which protects the potato. Every time the root is handled— from washing to the rollers, the boxes to the grocery store shelves— the potato gets a bump or nick. That allows for the introduction of bacteria, and the clock starts ticking on shelf life.