On the cusp of the 18th century, great changes were underway in the Gulf of Mexico. Spain’s almost two-centuries-long grip on the region was weakening, and rival European powers jockeyed for advantage. France, anxious to exploit Robert de La Salle’s Mississippi River explorations, dispatched a small fleet under the command of Pierre Le Moyne, Sieur de Iberville, in the fall of 1698. The English sent a squadron from the Carolinas soon after, but the French arrived first. Safely navigating the Spanish sea’s little-known and potentially dangerous northern littoral was another matter for them, however. They had no experience in those waters, and Iberville realized they needed a guide. It was thus that he came face to face with the fantastic figure of Laurens de Graff, better known as Lorencillo, the notorious Dutch buccaneer.

They met on the island of Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti), shortly after the French fleet stopped there in early December of 1698. Iberville commanded four ships — two 30-gun frigates with two smaller coastal craft lashed to their sides — and several hundred men. While in port, he linked with the bigger, 50-gun Francois under the authority of the Marquis de Châteaumorand. While their sailors provisioned and misbehaved on shore, Iberville and the marquis sought help.

|

It didn’t take them long to find Lorencillo. At the time, the Dutchman was living an idyllic existence as a respectably married planter. At 46 years of age, he perhaps assumed his sea-roving days were over. No one really knew much about his early life, but as a swashbuckling young man during the 1670s and ’80s, he had made himself the scourge of the Caribbean and Gulf. No less authority than Henry Morgan, governor of Jamaica and a former freebooter himself, called Lorencillo “a great and mischievous pirate.” His achievements included sacking the cities of Veracruz and Campeche, defeating a rival captain in a beach duel and capturing numerous Spanish ships laden with fantastic treasure. The Spanish called him El Griffe, a term connoting mixed racial heritage, but there is no definitive proof of that. Witnesses agreed that he was physically imposing and blond with a bushy mustache. Despite his fighting skills and fearsome demeanor, he was generally merciful to captives and seemed to bear the Spanish no personal animosity.

When Iberville and Châteaumorand learned that Lorencillo had spent time at Pensacola Bay and was familiar with the environs, they asked him to join their enterprise. The buccaneer was surely pleased to be offered legitimate employ, and he cheerfully signed aboard. (What his wife thought isn’t recorded.) In reporting the potentially controversial hire to France, the marquis stated: “M. de Graff, captain of a light frigate, has embarked with me. He has been a great help; more than a perfectly good sailor, he knows all the rocks and all the ports of that country there, toward the entry of the [Gulf of] Mexico, having sailed that course all of his life.” Besides Lorencillo, the French brought on some 20 of his buccaneer companions, thinking them no doubt worth their weight in gold if it came to fighting.

At last, on January 14, 1699, the enlarged French fleet rounded Cuba’s eastern coast and hove into the Gulf. Here Lorencillo proved his worth, guiding them past rocky Cape San Antonio, reassuring them that the Gulf Stream’s strong tug was not to be feared and that their course was good. Ten days later, through pesky winter fogs and rains, they made land a bit east of modern Destin. In a description that still holds true today, Iberville noted large “sand dunes … very white, ” backed by soaring pines. Because of shallow inshore waters, Iberville kept his larger vessels well off, using the lighter craft to coast west, taking soundings as they went. On Jan. 26, the vessels reached Pensacola, already occupied by a hardscrabble Spanish outpost consisting of a log fort and a few hundred scarecrows. When several officials came out to investigate the Gallic interlopers, they immediately recognized Lorencillo and must have feared the worst. Iberville and the marquis quickly reassured them, sending a basket of fine wines ashore and claiming they were merely searching for Canadian deserters. Doubtless the Spanish recognized a potential colonization effort if not a piratical enterprise and politely suggested the French keep moving. The irascible Lorencillo took advantage of the negotiations to brazenly sound the harbor entrance from a small boat and was brusquely ordered to desist by Spanish guards.

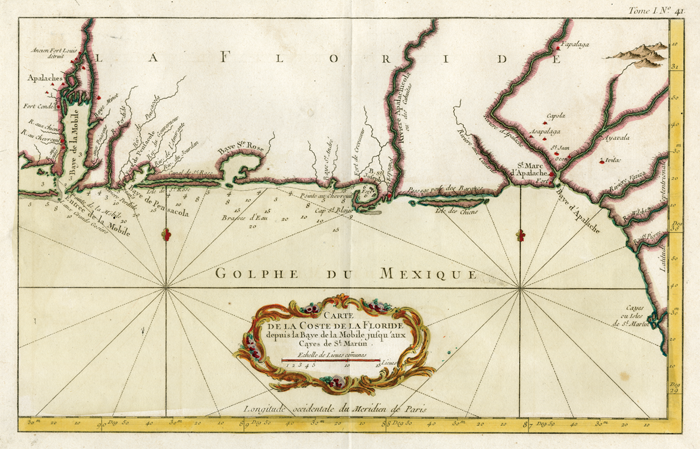

An early French map of the northern Gulf Coast, showing the numerous inlets, bays and rivers that Lorencillo helped them find.

Courtesy of the History Museum of Mobile

The following day the fleet anchored off Mobile Bay, its broad expanse no doubt inviting through chilly mist and mizzle. The French lingered several days and tentatively explored the area. Whether or not Lorencillo was with the shore parties that discovered piles of human bones on what became known as Massacre (later Dauphin) Island or that which camped with Iberville on the western shore is unknown. He was a sailor, not an explorer or a colonizer, and his expertise and interest stopped at the shore. Unable to find a good anchorage (that would come later), the French sailed west again, eventually coming to the mouth of the Mississippi. For his part, Lorencillo was growing bored. He told his employers he had no particular knowledge of the river mouth with its unglamorous and complicated driftwood flats, mud lumps and labyrinthine passages. And so, on Feb. 19, when Châteaumorand took the Francois back to Saint-Domingue, Lorencillo eagerly went along. The old pirate’s obligations had been well met. Thanks to his knowledge, his French hosts had safely probed the north shore and would go on to found lasting settlements at Biloxi, Mobile and New Orleans.

Lorencillo’s supporting role in local history has not been forgotten. In fact, there are those who argue that he is buried at Old Mobile, a persistent rumor no doubt occasioned by the fact that he died in 1704, at the same time as the settlement’s first yellow fever epidemic. While no reputable modern scholar believes this, his spirit certainly still haunts our shores, to the accompaniment of pounding surf and the seagull’s cry.

John Sledge is currently at work on “Coursing the Furrowed Blue, ” a maritime history of the Gulf.

Text by John S. Sledge