Carnival, or Mardi Gras, is Mobile’s greatest living tradition. An art form, an economic boon, a joyous celebration, and a family affair, the rituals and objects informing Carnival define Mobile. Textiles, such as this costume worn by Red Foster in the guise of Joe Cain, play a prominent role in the magic that is Mardi Gras in Mobile.

Joseph Stillwell “Joe” Cain (1832 – 1904) is both a historical figure and mythical character. Cain is best remembered for his special relationship to Carnival. It is in the realm of misrule that his actions — be they real or imagined — continue to shape the vision of not only Mardi Gras, but also the city in which it was first introduced to the United States.

Joe Cain was born on October 10, 1832, to Joseph Stillwell Cain Sr., and Julia Ann Turner. As with many Mobilians of the Antebellum era, his parents hailed from the Northeast and came to Mobile on account of its seemingly boundless potential for growth. Early in his career in the “Cotton City,” Joe Cain was employed in the cotton industry. The second-largest cotton exporting port in the nation, cotton made Mobile an incredibly wealthy city; earnings generated from cotton made for a lively social scene of which Carnival was the high point.

Cain became fascinated with Mobile’s Carnival culture as a child. By the 1830s, Mobile had established the template of mystic society culture in the United States: a parade for all people followed by an invitation-only ball. Joe Cain would have witnessed the spectacles of the Cowbellion de Rakin Society and the Strikers Club / Strikers Independent Society, two early mystic societies. At 14, he became a founding member of the Tea Drinkers Society, the third of Mobile’s mystic societies. In this period, Carnival events clustered around New Year’s Eve.

The Civil War curtailed annual Carnival celebrations. Joe Cain served as private in the Army of the Confederate States of America. The defeat of the South resulted in economic turmoil in Mobile, and Cain moved briefly to New Orleans in search of work. While in New Orleans, he observed the Crescent City’s Carnival festivities. They were similar to Mobile’s in most respects, only New Orleanians celebrated Carnival much later in the Carnival season, on the days leading up to and on Fat Tuesday itself.

Think you know Mobile Mardi Gras? Take our quiz to find out!

Upon his return to Mobile, Joe Cain was one among the many restless young men who sought both purpose and fun for themselves and others in what they found to be the bleak years following the Civil War. On Fat Tuesday of 1868, he was the leader of one of two groups who took to the streets. Dressed in fanciful Native American costume, Cain styled himself as a fictitious Chickasaw chief by the name of Slacabamorinico, and he and his cohorts referred to themselves as the Lost Cause Minstrels. As with all things Carnival, there was a layering of symbolism. The Chickasaw were the only one of Alabama’s principal Native American tribes to surrender to the Americans, and the Lost Cause referred to the defeated Southland.

Cain reprised his role as Chief Slacabamorinico (costume and all) each year until 1874. But Cain should not be seen as operating in a vacuum. The Order of Myths (OOMs), the oldest active parading society in the United States, staged their first parade the very same day as Joe Cain and the Lost Minstrels. The following year, the Infant Mystics (IMs) followed suit. Cain was, therefore, one among a number of individuals who revived and innovated tradition.

Upon his death in 1904, Joe Cain was buried in Bayou La Batre. He fell into relative obscurity. It was the Carnival-attuned interests of another Mobile son named Julian Lee Rayford (1908 – 1980) that lead to his “rediscovery” and reinvention. A journalist, folklorist, and artist, Rayford published “Chasin’ the Devil Round a Stump” in 1962. A popular and engaging chronicle of Mardi Gras in Mobile, the book is a mixture of fact and fiction. Rayford positioned Cain not as a seminal figure in Postbellum revitalization of Carnival, but as the savior of Mardi Gras itself. He persuaded city leaders to disinter Cain and his wife from their graves in Bayou La Batre and relocate their remains to Church Street Graveyard. Held on the Sunday before Mardi Gras in 1966, the featured procession resulted in such attention that the day was christened Joe Cain Day. Rayford donned a costume inspired by Cain’s, and the procession has been staged every year since. Red Foster and now Wayne Dean have followed Rayford as official representation of “Chief Slac.” The event is sometimes called the People’s Parade and allows anyone, be they member of mystic society or not, to parade in the streets.

Joe Cain’s impact on Mardi Gras is multifold. A day is named for him. Three organizations — the Merry Widows of Joe Cain, the Mistresses of Joe Cain, and Lovers of Joe Cain (apparently the guy got around…) — pay tongue-in-cheek homage to him. In life, legacy, mythology, and representation, Cain encompasses the popular appeal of Mardi Gras in Mobile.

Cartledge W. Blackwell III is curator of the Mobile Carnival Museum. He earned a BA in art history and historic preservation from the College of Charleston and an MA in architectural history from the University of Virginia. His research interests include 19th- and 20th-century Southern material culture.

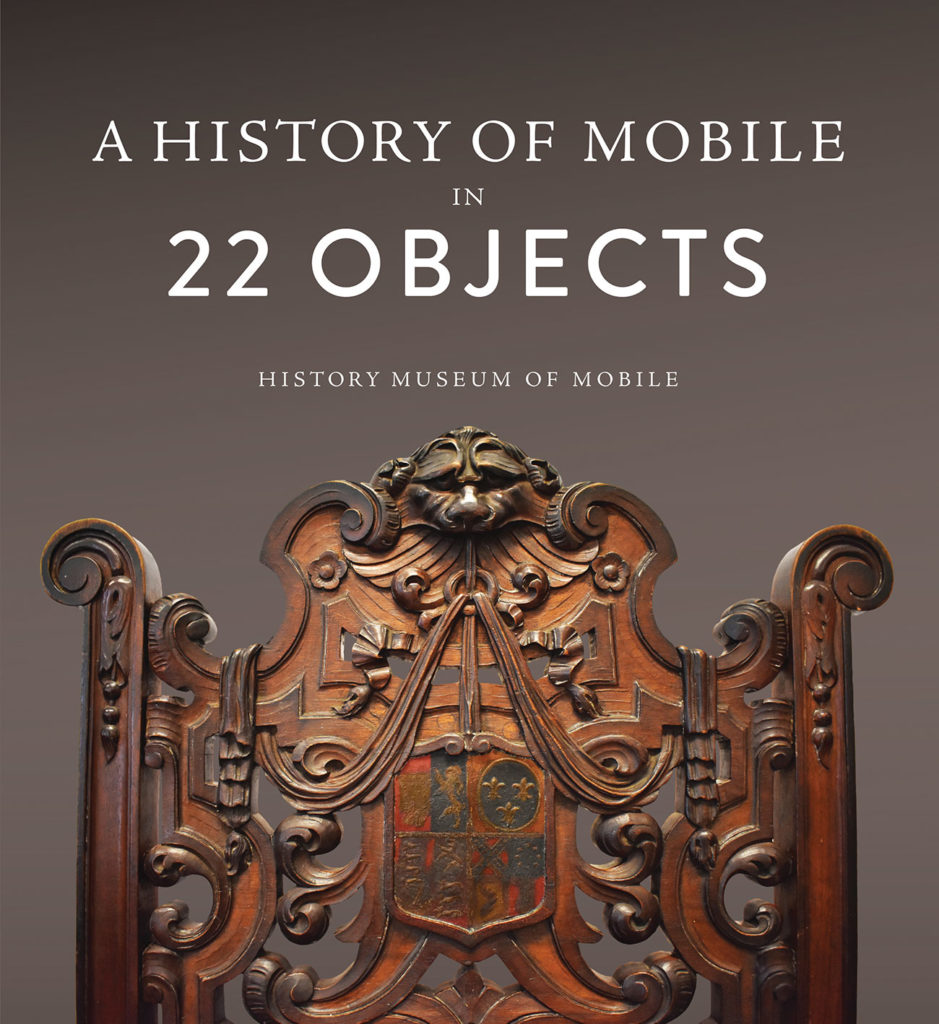

“A History of Mobile in 22 Objects” by various authors

Click here to purchase

Released in conjunction with the History Museum of Mobile exhibit, this photo-heavy compendium delves into the city’s history through the analysis of 22 artifacts by Mobile’s leading researchers.