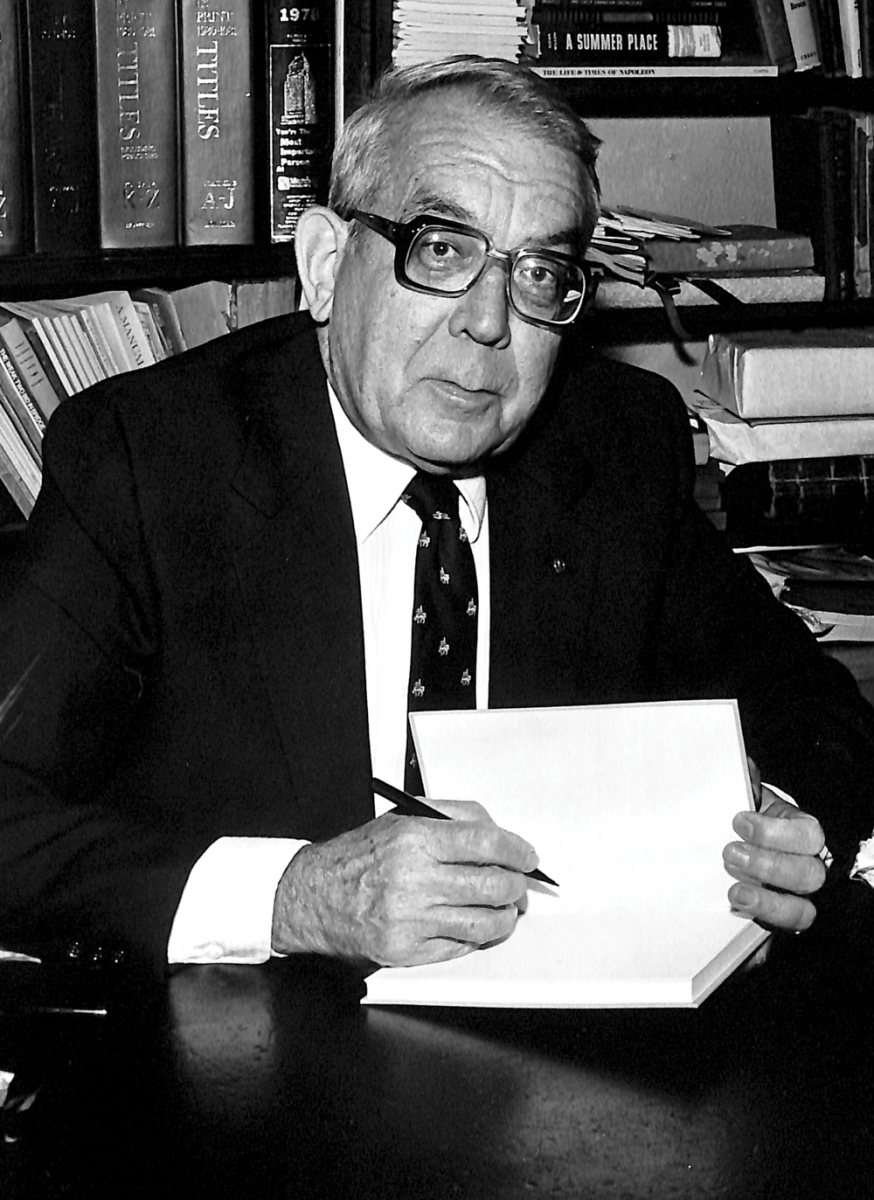

ABOVE LEFT Caldwell Delaney, author of “Remember Mobile.” Courtesy of History Museum of Mobile

ABOVE RIGHT Clark S. Whistler, illustrator of “Remember Mobile.” Courtesy of Caldwell Whistler

They were two very different men. The writer was a native Virginian who came to Mobile in 1930, and the artist was a Harvard-trained chaplain who had landed at Brookley Field while serving in the Army Air Corps. According to Caldwell Whistler, the latter’s son, Caldwell Delaney and Clark S. Whistler were “aware of each other’s talents if not exactly buddies.” Nonetheless, something sparked, and they decided to collaborate on a book about the pocketed coastal city they had both come to know. The result was a warm portrait in prose and drawings that celebrates its 70th anniversary this year.

“Remember Mobile” is very much in the genre of romantic, local-color books published during the 1930s and ’40s in other Southern cities. These volumes typically placed heavy emphasis on legend and story, with illustrations — usually watercolors or pen-and-ink sketches — that showcased architectural landmarks framed by familiar flora and foregrounded by quaint figures. They were more notable for their nostalgic tone than their scholarship, and their references to blacks are sometimes insensitive by modern standards. Despite these flaws, such books did much in their day to foster appreciation for historic architecture in their cities, and the historic preservation movement owes much to their influence.

By the time he put pen to paper for “Remember Mobile, ” Caldwell Delaney was thoroughly embedded in the Port City’s distinctive culture and traditions. He was serving as the dean of the University Military School, where he taught a memorable local history course (future historian Walter Bellingrath Edgar was among his students); ran with a crowd that included Adelaide Marston Trigg, Eugene Walter and other Haunted Book Shop regulars; and was an enthusiastic antiquarian. His Black Belt rambles had already produced the 1941 edition of “Deep South, ” an affectionate survey of Alabama plantation homes deftly illustrated by Frank Kearley. Whistler was less rooted because of his active military service and, in fact, did the “Remember Mobile” sketches from photographs while serving with the Army of Occupation in Germany.

By the time he put pen to paper for “Remember Mobile, ” Caldwell Delaney was thoroughly embedded in the Port City’s distinctive culture and traditions. He was serving as the dean of the University Military School, where he taught a memorable local history course (future historian Walter Bellingrath Edgar was among his students); ran with a crowd that included Adelaide Marston Trigg, Eugene Walter and other Haunted Book Shop regulars; and was an enthusiastic antiquarian. His Black Belt rambles had already produced the 1941 edition of “Deep South, ” an affectionate survey of Alabama plantation homes deftly illustrated by Frank Kearley. Whistler was less rooted because of his active military service and, in fact, did the “Remember Mobile” sketches from photographs while serving with the Army of Occupation in Germany.

Gill Printing Co. published the volume in 1948 to appropriate fanfare. The first edition is a glory. Weighing in at better than 3 pounds and measuring over 8-by-11 inches, it features a cream-colored, full-cloth cover, 242 Smyth-sewn high-rag content pages and beautifully clear print. Subsequent editions of “Remember Mobile, ” in 1969 and 1980, are of lesser quality but did serve to keep the volume in circulation.

Delaney knew how to turn a phrase. In his preface, he acknowledged that there are, in fact, many Mobiles. For some, especially tourists, he wrote, “Mobile is the flaming, neon-brilliant display of azaleas in the spring.” To others, it “is the expectancy that precedes a Mardi Gras parade, and the thrill of the grotesque torch shadows on ancient trees as the great lumbering floats pass by like visions of another world.” To harmonizers, the city “may suggest a tropical moon glimmering across black water, ” with “pines silhouetted against the stars and great live oaks dropping their festoons of Spanish moss into the shadows, ” and to the practical it “is an industrial center and seaport located at the head of Mobile Bay, 30 miles from the Gulf of Mexico and at the southern extremity of the Alabama-Tombigbee delta.” Clearly, Delaney recognized all of these Mobiles and knew how to evoke them.

Given his tastes, Delaney was especially enamored by the city’s long colonial history. More than half of “Remember Mobile” expounds upon it in florid chapters such as “Days of Blood and Gold, ” “The Lilies of France, ” “Bienville’s Capital” and “The Castles of Spain.” The author’s love of romance often clouded the historical reality, as when he wrote of Gov. Cadillac’s early 18th-century tenure: “For the first time in its young life, the capital of Louisiana began to look as well as feel a little like Paris. For Madame Cadillac and her daughters had brought with them the style of Paris as well as the furniture.” To be sure, Cadillac and his family enjoyed amenities unavailable to Mobile’s rude soldiers and coureurs de bois, but the city was no Paris. The book goes on to cover the early 19th century, the cotton boom and the Civil War, concluding with Reconstruction. In a short coda, Delaney highlighted a few enduring customs and a favorite old Mon Louis Island restaurant, alas gone. His descriptions of the gumbo, “platters of fried fish, shrimp creole, oysters creole, fried shrimp, stuffed crabs” and “thick black coffee” practically waft off the page.

ABOVE LEFT The Staples House, 1852. This house still stands at 1614 Old Shell Road. Courtesy of History Museum of Mobile

ABOVE RIGHT John Craft House, 1855. Corner of Conti and Jackson Streets. Courtesy of History Museum of Mobile

Throughout the book, Whistler’s wonderful sketches reinforce the romantic tone, even though they aren’t coordinated to the text and, with few exceptions, aren’t even mentioned. They are there rather for effect. For example, an illustration of the Admiral Semmes House on Government Street from 1858 is placed in the chapter about 16th-century Spanish entradas. All of the buildings Whistler sketched existed when the book was produced, and many still do, such as Barton Academy, the Bragg-Mitchell Mansion, Stewartfield and Washington No. 5 Firehouse. Unfortunately, others have succumbed to the wrecking ball, like a rustic trio of Creole cottages pictured cheek by jowl on a riverfront street.

Whistler’s eye for architecture was superb. His sense of proportion was correct, and he precisely depicted historical ornamental details, even the exact number of window panes present in the sashes, which less disciplined or less observant illustrators rarely do. Overall, the artwork is as good as the prose, if not superior given Delaney’s occasional penchant for hyperbole.

Because of its errors and insensitivities, “Remember Mobile” cannot be considered a reliable introduction to Mobile history. But it still has value as something of a period piece, an affectionate homage to a very special town.

Copies of all three editions of “Remember Mobile” may be found online at sites like AbeBooks and Amazon. Of course, the original 1948 edition is the one to own.

John S. Sledge is the author of “Coursing the Furrowed Blue: A Maritime History of the Gulf, ” to be published in 2019 by the University of South Carolina Press.