The bold, black headline of the April 29, 1951, edition of the Mobile Register exclaimed, “Robert Vogeler, Cold War Pawn, Returns to U.S.; Former Mobilian Meek and Trembling …”

Vogeler, a 38-year-old executive with International Telephone and Telegraph, was pulled from his car by two Hungarian soldiers armed with machine guns on November 18, 1949. Accused of being a spy, he was beaten, drugged and interrogated for his first 65 hours of imprisonment. His windowless cell adjoined a room where his fellow prisoners were tortured day and night. “Their screams drove me to distraction, ” he would later recall.

Despite protests from the United States and the closure of Hungary’s consulate in New York, no one from the West would see Vogeler for nearly a year and a half. His eventual release, some 17 months later, came after the U.S. paid millions of dollars to Hungary — a sum that the nation claimed the Nazis had taken from them and the Americans had later confiscated. Other prisoners were not as fortunate. One of Vogeler’s associates, a U.S. Naval attaché, vanished only to be found crushed under the wheels of the Orient Express in an East German railway tunnel.

|

From Annapolis to Mobile

Though the newspaper termed Vogeler a Mobilian, he was actually a native of the New York borough of Queens. He had entered the U.S. Naval Academy but resigned his commission in 1931, and two days later married a very wealthy Mobile widow named Debe Hubbard. He was 20, and she was approaching 35.

A decade earlier, Hubbard had scandalously married the recently divorced banana importer Ashbel Hubbard. He was some 30 years her senior and had amassed an impressive fortune as the partner of Samuel Zemurray, a principal in United Fruit Company. Based on the corrupt dealings of that firm, Alabama playwright Lillian Hellman chose the name Hubbard for the villainous clan in her hit “The Little Foxes.”

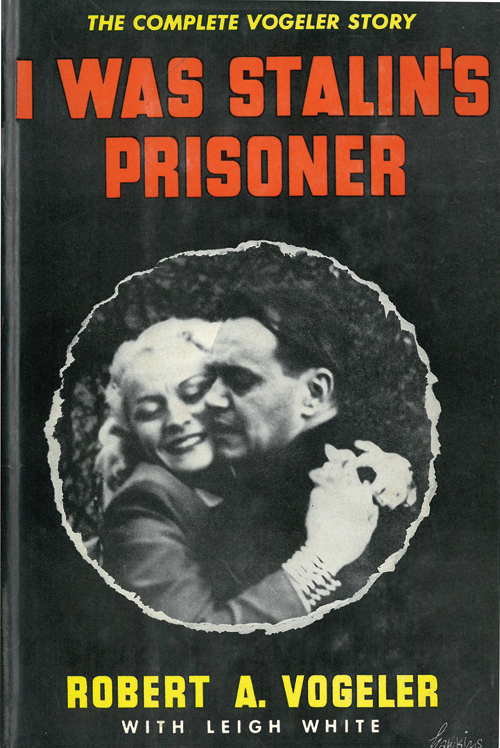

In writing a book about his experiences, Vogeler later stated that he and his new bride had left on an extensive European honeymoon and found their stay in Budapest particularly memorable.

Upon his return to Mobile, he “entered the tire and rubber business with a friend of mine named Pat Feore.” Feore had the distinction of reigning as King Felix during the 1928 Mardi Gras sea- son but last appears in the 1931 Mobile city directory where his occupation was listed as a car salesman.

The city directories first list Vogeler in 1933, noting his occupation as “broker.” No occupation appears beside his name in the next two directories. By 1936, he and Debe had divorced, and it is doubtful that he ever came to Mobile again.

Debe died in 1949 while her former husband languished in the Hungarian prison. Vogeler was able to return to his second wife and two sons, and he left the business world to teach in a parochial girls school in Greenwich, Connecticut. He died in 1992 at the age of 81.

Text by Tom McGehee