They were some of the ungainliest vessels to ever enter Mobile Bay. The five big, pine-log rafts, each better than 30 feet long, rode low in the water and were arrayed with short masts, braided horsehair rigging and patchwork sails. It was early November of 1528, and the little flotilla carried the desperate remnants of Panfilo de Narváez’s ill-starred expedition.

The men had not started out in such dire condition. Borne by trim caravels, they had landed at Tampa Bay the previous spring and steadily pillaged their way up the Florida peninsula, seeking Indian gold such as Cortés had encountered in Mexico. Their leader, Narváez, was notoriously cruel, and his scorched-earth tactics turned the brutalized native peoples into deadly foes. Frustrated by the country’s lack of precious metals, low on food, wracked by disease and beset on all sides by Indian warriors, the Spaniards decided to abandon their quest and try to reach Mexico (or New Spain as they called it) by sea. That autumn, they camped on Apalachee Bay to build their boats.

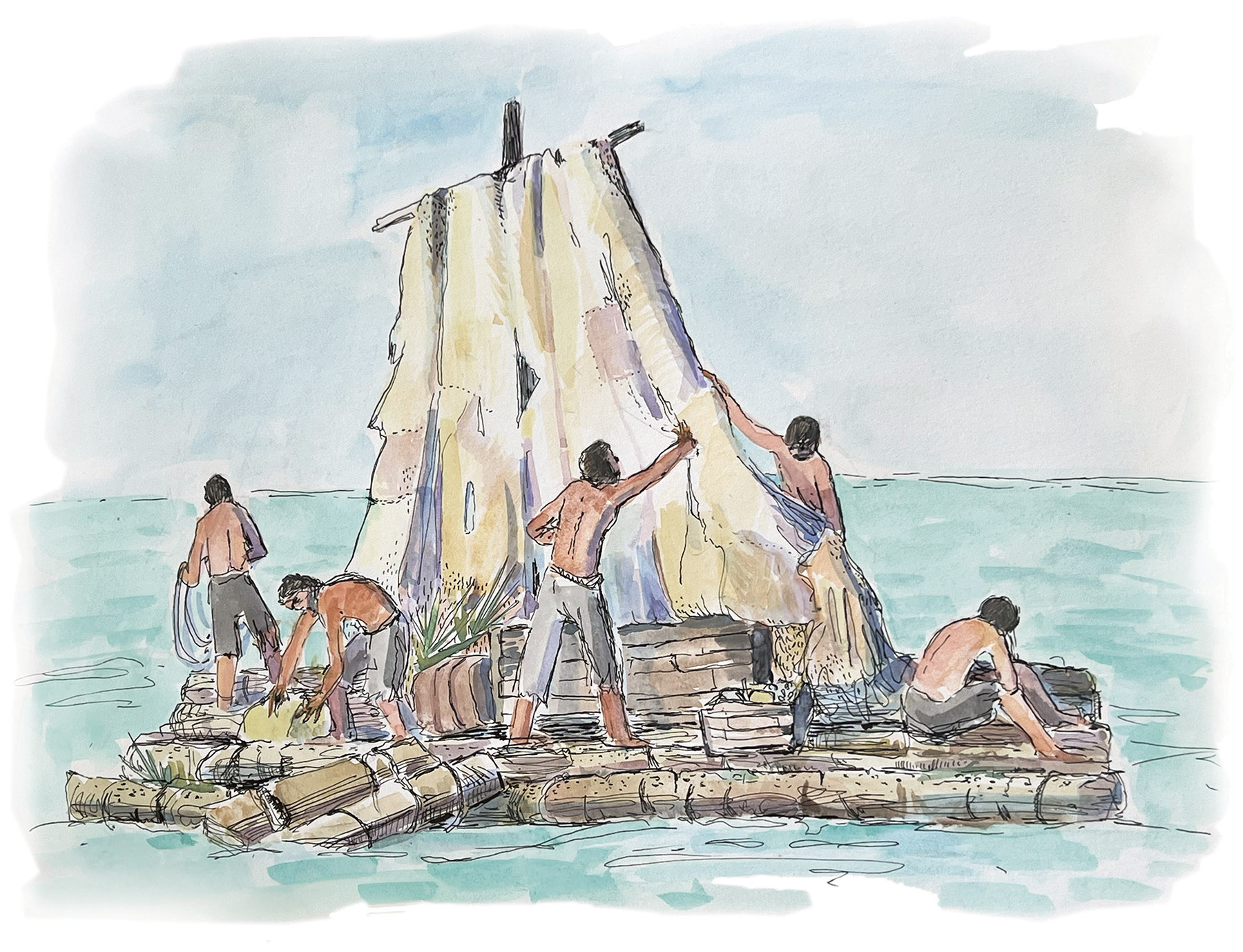

Few of the men had any boatbuilding experience, but guided by a skilled Greek carpenter named Doroteo Teodoro, they quickly got to work. Using a makeshift forge, they melted their armor, stirrups and crossbows to fashion saws and nails. Sweating axmen cut down tall trees and stripped the limbs and bark. Every few days they killed one of their horses for food, saving the coarse manes and tails for rope and the hide for water containers. The strongest men positioned the dressed logs and lashed them together with the horsehair rope while other soldiers gathered palmetto fronds to stuff between the cracks. Smaller work parties made serviceable masts and oars out of slender cedars, while men seated in the sand sewed square sails from shirts, rags, and worn-out pantaloons. Upon completion, each raft weighed 15 tons and carried 50 men along with water, corn and the remaining weapons. Once afloat, they had at best seven or eight inches of freeboard, hardly an ideal circumstance on the unpredictable Gulf.

Narváez commanded the lead raft and various officers the others. Among the latter was Cabeza de Vaca, the expedition’s treasurer and later the author of an incredible travel account. (His unusual name, meaning “cow’s head,” was derived from a medieval ancestor who had marked a critical mountain pass with a bovine skull to guide Spanish forces against the Moors). By the time the little flotilla reached Mobile Bay, it had suffered pelting chilly rain, rough seas and frequent Indian attacks whenever it landed to replenish food and water. Both Narváez and Cabeza de Vaca took bruising sling stone hits, and the exhausted men were losing hope. “As we brought little water and the vessels were few, we were reduced to the last extremity,” Cabeza de Vaca later wrote. “Following our course,” he continued, “we entered an estuary, and being there we saw Indians approaching in a canoe. We called to them, and they came.” Mobile’s colonial historian Peter J. Hamilton believed the Spaniards had worked up the Bay until reaching the mouth of Fowl River.

The Indians approached Narváez’s raft first. By means of sign language he asked them for water. They agreed but, not having any containers, requested several of the horsehide buckets. And then an extraordinary thing happened. Teodoro the Greek insisted on going with them to get the water. This request surprised Cabeza de Vaca just as much as the other Spaniards. “The Governor [Narváez] tried to dissuade him,” he remarked, “and so did others, but were unable; he was determined to go whatever might betide. Accordingly, he went, taking with him a negro, the natives leaving two of their number as hostages.” The Spaniards watched Teodoro and the Black man clamber into the unsteady dugouts and settle as young indigenous warriors dug their paddles into the tawny water. There was nothing left to do but wait and hope.

At dusk the Indians returned, but without Teodoro and the Black man. Tensions rose. Narváez demanded his men’s return, and the Indians shouted to their companions on the raft to jump. Alert Spaniards restrained them, and amid reproachful looks and glares the Indians retreated. Hardly knowing what to do, the Spaniards floated all night, “sorrowful and much dejected at our loss.” They dared not land, fearing ambush.

Morning brought an escalation. More warriors appeared, including at least five chiefs, impressive, well-formed individuals with flowing black hair and majestic fur robes. “They entreated us to go with them,” Cabeza de Vaca later wrote, “and said they would give us the Christians, water and many other things. They continued to collect about us in canoes, attempting in them to take possession of the mouth of that entrance; in consequence, and because it was hazardous to stay near the land, we went to sea, where they remained by us until about mid-day.” There, just outside the Bay’s mouth, the two sides bobbed in their respective vessels — hodge-podge rafts and dugout canoes — waiting to see who would make the first move.

Neither Narváez nor the chiefs agreed to part with their hostages. Patience at last exhausted, the Indians started slinging stones and throwing spears at the Spaniards. “While thus engaged,” Cabeza de Vaca recalled, “the wind beginning to freshen, they left us and went back.” The dugout canoes were even less suitable on the open Gulf than the rickety rafts. Thanks to the weather, the Spaniards avoided a nasty fight, the outcome of which was by no means certain. They continued westward without their friends. As for the Indian hostages, Cabeza de Vaca makes no further mention of them. The Spaniards most likely tried to use them as interpreters.

But what of Teodoro and his companion? Years later, Cabeza de Vaca would learn their fates. When Hernando de Soto’s army marched along the Alabama River in the fall of 1540, they rested at an Indian village called Piachi, located near present-day Selma. According to Luys Hernández de Biedma, a royal official in Soto’s entourage, “Here we had news of how the boats of Narváez had arrived in need of water, and that here among these Indians remained a Christian who was called Don Teodoro, and a Black man with him.” As proof, the Indians showed the Europeans a small dagger. They said they had killed the two men but did not say when or give a reason.

Based on Cabeza de Vaca and Biedma’s accounts, it seems clear that Teodoro meant to desert and make a new life among the Indians. The Black man, probably enslaved, likely had no say in the matter. How long did these two survive afterwards? Did they accompany the Indians upriver, marry native women and live at Piachi? Did the Indians kill them because of some offense or to appease an enemy or an angry deity? The answers are, alas, unrecoverable at this distant date. But such were the fates of the first Greek and the first Black man in Mobile Bay history.

John S. Sledge is coauthor of “Mobile and Havana: Sisters Across the Gulf,” available in bookstores locally and online at the universityofalabamapress.ua.edu.