In Mobile, we like to throw around the phrase, “the original Mardi Gras, ” and we often claim that we had it. We get a little huffy with anybody who disagrees; anybody who disagrees is probably a Communist, even from New Orleans.

Well – maybe not.

Let’s back off and think about it. Not to be too Clinton-esque and all, but it depends upon what “the original Mardi Gras” means. It’s a troublesome phrase, and it overreaches. We probably ought to say instead that “Mobile is the Mother of Mystics, ” which it clearly is. Why gild the lily?

Claims Versus Facts

First, let’s go back to all that talk of Carnival in Mobile in French Colonial times. I’ll spot you that at Mardi Gras back then, maybe some French soldiers or French-Canadian moccasin-clad “Coureurs deBois” drank too much red wine with their deer meat or boiled buffalo (yes, we had bison then) down here in South Alabama. If you think that gives Mobile “the original Mardi Gras, ” well then, you are entitled to think it. To me, that does not support the grandiose claim. And anyway, it would likely have been on what they named “Mardy Gras Bayou, ” generally thought to be in Mississippi.

Yeah, but all that French Colonial Mardi Gras stuff that people around here keep repeating, what about it? Like the claim that some Frenchmen back in the 1700s had a Mardi Gras parading society called the Societé de Boeuf Gras, and that they had a papier maché bull’s head on wheels that they rolled around like Spanish bullfighters do, and that when The Late Unpleasantness hit in the 1860s, they used the papier maché from that bull’s head as cannon stuffing and shot it with cannonballs at Yankees. What about all that?

Well, prove it, I say. Show us one original document proving that. I don’t mean some popular Mardi Gras history book written in modern times, fluffily claiming it. I mean prove it. Show me some hard evidence, like a French diary or document or report that says that. I have read the best sources, like d’Iberville’s journal and the Penicaut narrative, and they don’t mention it. I have even asked actual historians, who understandably would not publicly touch this issue with a 10-foot pole, but who clearly aren’t taken in by the tale.

You cannot prove it. Nobody can. Somebody just invented that stuff out of whole cloth. Who? The best old Mobile historians named to me a likely suspect, but they went to their graves without blowing his cover publicly. It isn’t my job to out the old boy on his perfidy, but I call “bullshit!” You cannot prove that the Frenchmen in old Mobile had anything that would support a serious claim that we invented Mardi Gras.

I say that “Mobile is the Mother of Mystics, ” rather than that we have “the original Mardi Gras.” Why do we need to gild the truth? The truth is magnificent.

Mobile invented the way that both New Orleans and Mobile now celebrate Mardi Gras — the themed parade with illuminated floats, the turnout of the population for the parade, and the celebration of the Mystic society after the parade. Mobile clearly invented that. But when Mobile invented all this, it was originally something done on New Year’s Eve and not on Mardi Gras. Can New Year’s Eve be “the original Mardi Gras?” You must admit that it’s pushing the issue to claim that.

Cowbellion de Rakin Society’s Big Debut

OK, so when did all this parading Mystic society stuff start here in Mobile? According to an 1890s newspaper article, it was Christmas Day in 1831. Michael Krafft, a local cotton broker who was described as a man of “infinite jest and fond of fun of any kind, ” who had “a cocked eye which gave him a quizzical appearance, ” was down at the waterfront and got into a wine-filled Christmas dinner on the sailing ship of a sea captain named Joseph Post of the Hurlbut Line of New York packets. Post was known as “Pushmataha” or “Old Push” after the Choctaw chief who sided with the whites in the Creek Indian War. Krafft and Old Push made a day of their winey luncheon, and Krafft didn’t leave until about nightfall. Krafft came out into a cold drizzle and borrowed a sailor’s sou’-wester hat and a “monkey jacket” to sortie out from the ship.

You know the basic story. Krafft walked down to Commerce and Conti Streets at Joseph Hall’s hardware store and leaned against some rakes and cowbells in a sort of rustic display out front. They made a racket. Just for fun — everything in Mardi Gras is just for fun — he put the cowbells on the rake and paraded up and down the bar area ringing the cowbells. A passerby asked, “What society is this?”

And Krafft said, “This? This is the ‘Cowbellion de Rakin Society!’” He then fell in with James Taylor, “Jim, ” the forgotten cofounder of Mobile Mysticism. They paraded around and rode a mule into a saloon on Exchange Alley, to the general delight of the tipplers and drunks in the bars on Christmas night.

During the week between Christmas and New Year’s of 1831, newspapers demanded that the Society turn out again on New Year’s, and they did. A group of men stood around the E.P. Dickinson Clothing Store on Dauphin Street. Later, in the 1890s, Mayor Pat Lyons said that right then and there was the beginning of the Cowbellion de Rakin mystic society. The crowd, 40 or 50 strong, assembled in the upper floor of a coffeehouse on Exchange Alley, and at about 9 p.m. on New Year’s Eve, they began parading. Mayor John Stocking sent a messenger to invite them to his house, and after the parade, they joined him for a big spread of food and drink and later visited some local oddball that Lyons would call “the original George Davis.” Ultimately, they marched back to the coffeehouse and dispersed. And that was our “original Mardi Gras, ” but it was on New Year’s Eve, not Mardi Gras.

Michael Krafft died in 1832 before the second parade, but that year the Cows picked up speed, and at least by 1842, the Cows had a theme and a parade with torches, floats, transparencies for lighting and all the mystic stuff that we now identify with Mardi Gras — but it was still New Year’s Eve.

More Societies Follow Suit

By the 1840s, the Cowbellions had gotten to be a stuffy champagne-drinking society that took itself very seriously — so much so that when the Strikers were formed in 1842, they made fun of the uptight Cowbellions by adopting bock beer as their official drink, rather than the Cows’ champagne. The Cows were organized along military lines. “The Captain” was in charge, and they had a secret committee, a blackball system and a ritual initiation, just like some — or maybe even most — of the stuffy old Mardi Gras mystic societies we have today in Mobile. Although by the 1850s Mobile had at least three New Year’s Eve parading mystic societies, (the Cows, the Strikers and the T.D.S., which stood for “The Determined Set”), Mobile did not yet have a Mardi Gras parading mystic society.

The Transition from New Year’s to Mardi Gras

At some point, the floats, the parade, the crowds and the party afterward migrated from New Year’s Eve to Mardi Gras. When? Why? Not enough Mardi Gras historians have focused on when or why that happened, probably because the entire issue casts doubt on our dubious claim to have “the original Mardi Gras.” I have good reason to believe that it was between 1881 and 1889.

Mystic societies made the jump to Mardi Gras in New Orleans before we did in Mobile.

We have to give New Orleans its due. The first parading Mardi Gras mystic society was the Mystick Crewe of Comus, in New Orleans, held February 24, 1857.

But, it is widely known, even in New Orleans, that Mobilians played a prominent role in the founding of Comus. The group proclaims that the men who helped found it were Mobile Cowbellions who had moved to New Orleans: S.M. Todd, L.D. Allison, J.H. Pope, Frank Shaw Jr., Joseph Ellison and William P. Ellison. We also know that the new group apparently acquired (and probably bought) the costumes, floats, flambeaux, and even theme — not to mention their very name, Comus — from the 1856 Cowbellion parade (Milton’s “Paradise Lost”). There are also indications that Strikers from Mobile were involved, and they went en masse to the first Comus event.

Reconstruction of Carnival in Mobile

OK, so back to Mobile. We all know that during reconstruction Joe Cain put on the costume of the fictional Chickasaw Chief “Slacabamorinico” and led the local spirits in a Mardi Gras parade to perk them up a little, and all that. Oddly enough, Joe Cain, who is revered as founder of Mobile’s Mardi Gras, was a member of the T.D.S., a New Year’s Eve parading society. There is no evidence that he was ever a member of a Mobile Mardi Gras mystic society.

In 1867, 10 years after Comus was established in New Orleans, the Order of Myths was founded as the first Mobile Mardi Gras parading mystic society. And, the next year the Infant Mystics were founded as the youthful “Gumdrop Rangers.”

Mysticism in Mobile during the 1870s was sort of catch-as-catch can, for both New Year’s Eve and Mardi Gras. Some mystic societies paraded on December 31 for a while longer, until Mardi Gras eclipsed New Year’s in the mystic world of Mobile.

But the biggest puzzle of all about Mystic Mobile is this — how and why did mysticism in Mobile move from New Year’s Eve to Mardi Gras? That mystery includes other big questions about mystic Mobile. What happened to the Cowbellion de Rakin Society? Before, during, or after its collapse, did the Cows join other societies, or not? And if so, which one? There are lots of vague legends and unsupported notions, but nobody has ever made a study of it. It is not a secret. Most of it is in readily available records in the public libraries — but apparently nobody has ever done the work to study it, put it together and write it down. You saw it here first.

Cow Mergers

In 1878, the society’s secretary noted about 120 living Cowbellions, 82 of whom signed their 1878 Constitution. (A few more signed a resolution.) Some of them had an illegible hand, but I have identified 104 Cowbellions by name, who were recognized by the group during the 1870s and ’80s.

The legend among old Mobilians who are mostly dead now was that the Cows got so full of their own importance that they stopped voting people in and died out. But even if that’s part of the story, it certainly isn’t the full one. In any event, they certainly didn’t stop voting people in until fairly late in the game — the 1880s, maybe — if ever. Of the 101 Cows identified by initials and date of initiation in the Cowbellion 1878 Constitution, only four were initiated before the Civil War! At least 95 new members were initiated in the 14 years between the end of the Civil War and 1879, six or seven per year on average. Very few mystic societies today do much (if any) better than that. The Cows were holding their own.

But the OOM was founded in 1867, and beginning in the first two years of its history, some Cows started joining it, most staying in the original group, too. By the end of the 1870s, about 16 percent of the Cows had joined another society; that hurts, though most of them also stayed in the Cows until the 1880s.

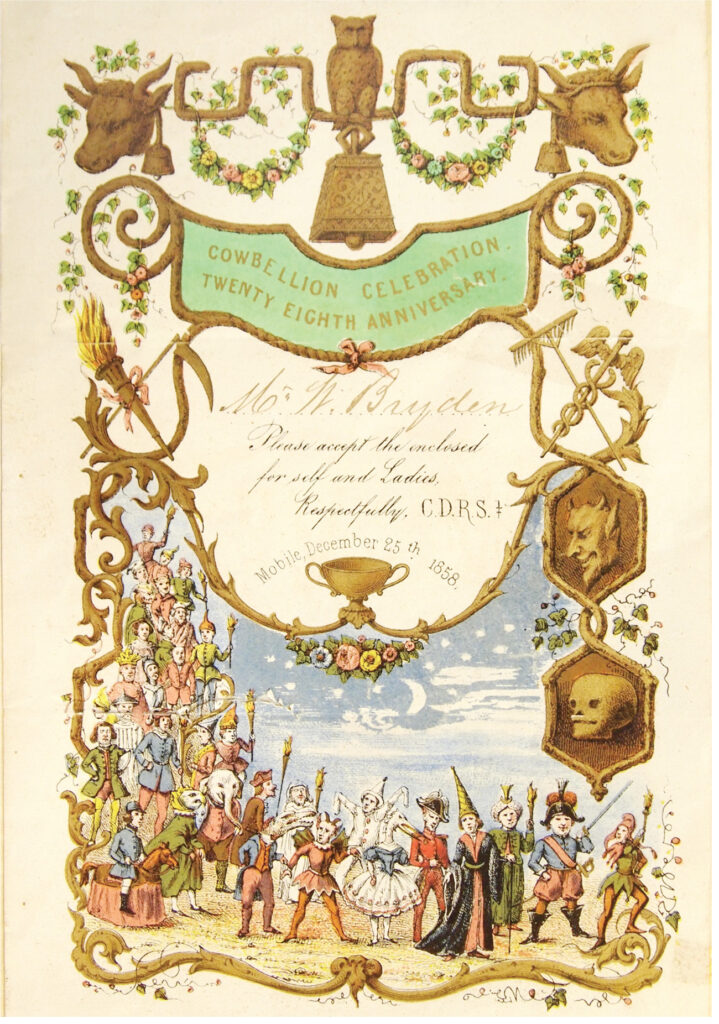

By 1880, New Year’s Eve mysticism was dying out in Mobile. But for Dec. 31, 1880 there was one final rally, which set the high-water mark of Mobile’s New Year’s mysticism. It was the so-called Semi-Centennial of Mysticism, the 50th anniversary of New Year’s mysticism in Mobile. The Cows, the Strikers and the T.D.S. hosted a joint celebration, with an invitation and program, right, quite rare today, showing the Cowbellion owl with a clutch of eggs including the Strikers and the T.D.S. It looks grand in retrospect, but it was the death rattle of Mobile’s New Year’s Eve parading mysticism.

During the 1880s, at least 11 more Cows joined the OOM, bringing the number of members going to the OOMs to 27 in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s. That’s a loss of at least 27 percent of the Cows’ members to the OOMs by the 1880s. That really hurts.

As a result, in the late 1800s there was an abortive attempt to merge the OOMs and the Cows into a single group called the “Michael Krafft Society” after the founder of the Cows, but it fizzled. After the early 1890s, the Cowbellions were never heard from publicly again. By then, they were getting a little age on them and probably just dropped out of parading life. It takes a lot of people and money to pull off a parade and dance.

The Extinction of New Year’s Mysticism

Mardi Gras historians don’t talk about it, but Erwin Craighead, editor of the Mobile newspaper after the Civil War, always had a theory that one of the things that killed New Year’s mysticism was that Mobile adopted what he considered a Yankee custom. On New Year’s Eve or Day, homes would be open for society callers. Supposedly wives and mothers insisted the men be there and be reasonably sober. He added that it was tough to change into and out of formal clothes for both the dances and the open house. Might be.

In October of 1894, the Great Veiled Prophets Pageant in St. Louis put on a parade on the theme, “History of Mystic Societies in America, ” with the papers noting that “The Historic City of Mobile, which lies at the mouth of the Alabama River and close by the Mexico Gulf, is the mother of mystics in this country.” This is apparently the first recorded use of the term “Mother of Mystics, ” for Mobile, a term which I believe Mayor Pat Lyons coined. The first float represented Mobile’s “Cowbellion de Rakian Society, ” adopting Pat Lyons’ preferred nomenclature of the Cows; the second Mobile’s Strikers, and the third, Mobile’s T.D.S.

“Mobile, Mother of Mystics.” Now that’s accurate. We were and are that. But you have to push it too far to say that we have “the original Mardi Gras.”