Colorful threads symbolically stretched across black and white photographs. Thirty-five millimeter film mounted onto baby doll heads. A miniature banjo here. A modified Mexican street camera there. An endless collection of international souvenirs, keepsakes, trinkets, art equipment and astonishing creations. Even Sesame Street’s ole Bert and Ernie would be forced to say, “None of these things are quite like the other.” But, they are just a few of the fascinating objects you’ll find inside the magical Fairhope home of Marion Winchester “Pinky” Bass.

Tucked behind a quiet wall of green, just a block from the hustle and bustle of downtown Fairhope, sits Pinky’s home, the simple wood exterior giving way to a kaleidoscope of imagination inside. It is quickly apparent that this is no ordinary house and Pinky is no ordinary artist. The unpainted board and batten structure is the perfect blank canvas for Pinky’s collection of curiosities and awe-inspiring work. At 83-years-young, the woman whose nickname was coined by delivery room nurses for their admiration of her red hair is just as witty, perceptive and sharp as ever. With one step through the front door, you’ll find yourself in her living-room-turned-studio, surrounded by a deluge of artistic paraphernalia and homemade cameras, as well as dozens of intriguing photographs taken by Pinky herself. That’s because she’s best known not only for her spirited banter and sprightly demeanor but also for her creative work with photography.

Discovering the Lens

Despite having been born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Pinky travelled every summer to visit family in Fairhope. She descends from a line of artistically talented women: Her mother, Marion McCall, was a highly skilled and accomplished abstract watercolorist. Pinky’s sister Frances was musically gifted, even crafting her own instruments by hand, and their grandmother Lois Slosson Sundberg created beautiful photography in the 1800s. In fact, the Slosson family, having lived in Silverhill for a time, was friends with Frank Steward, known throughout Baldwin County as the “Picture Man.” Pinky says that Steward probably taught darkroom techniques to her grandmother.

Pinky was a Biblical studies major during her time at Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Georgia, but she dabbled in the arts on a regular basis. “I initially thought I was going into drawing and painting,” she says, “but I [eventually] discovered photography and realized that it was my voice.” When Pinky settled in Fairhope, her Aunt Ruth offered up grandmother Sandberg’s glass negative camera and the old glass negatives from a Magazine Cyclone No. 5 glass-box camera. It was clear her grandmother had an eye for images, and Pinky surely inherited that gift.

Through The Pinhole

Pinky experimented with drawing and traditional photography for years, but it wasn’t until her 50s that she was able to give her art the attention it deserved. Divorced and with grown children who were beginning their own lives, she turned her focus to expanding her creative vision. During graduate school at Georgia State University, she quickly became disenchanted with regular 35-millimeter film and felt an insatiable longing to articulate her creativity through the lens in a more unique and visual way. Little did she know that she was on the verge of embracing a technique that was destined to become her signature style and would forever change the way she viewed the world.

“My major professor said to me, ‘Have you ever thought about trying pinhole?’”

Pinky’s insatiable curiosity was piqued. She did some investigating and soon discovered that virtually any object could become a camera. From tubes of lipstick to giant mobile campers like the once-famous Pinky’s Portable Pop-up Pinhole Camera and Darkroom — which she drove throughout Alabama introducing photography to students of all ages — the possibilities were seemingly endless.

“I like the idea that anything you can make into a black box can be a camera,” she says. “I must have about a hundred things in my house that are cameras. For me, this is what pinhole became. It was all about discovering the science of photography.”

In addition to the science of film and the engineering of construction, pinhole photography is about embracing the unexpected. Because of this method’s use of a smaller aperture — a pinhole — the resulting infinite depth of field allowed for the likelihood of creative mistakes, something which further enchanted Pinky and appealed to her artistic nature.

“You never know what is going to happen,” she explains. “I just love it when things go wrong or mess up. It’s delightful.” This attraction toward a lack of control is evident not only in her photography, but in much of her other work, too.

Another Layer

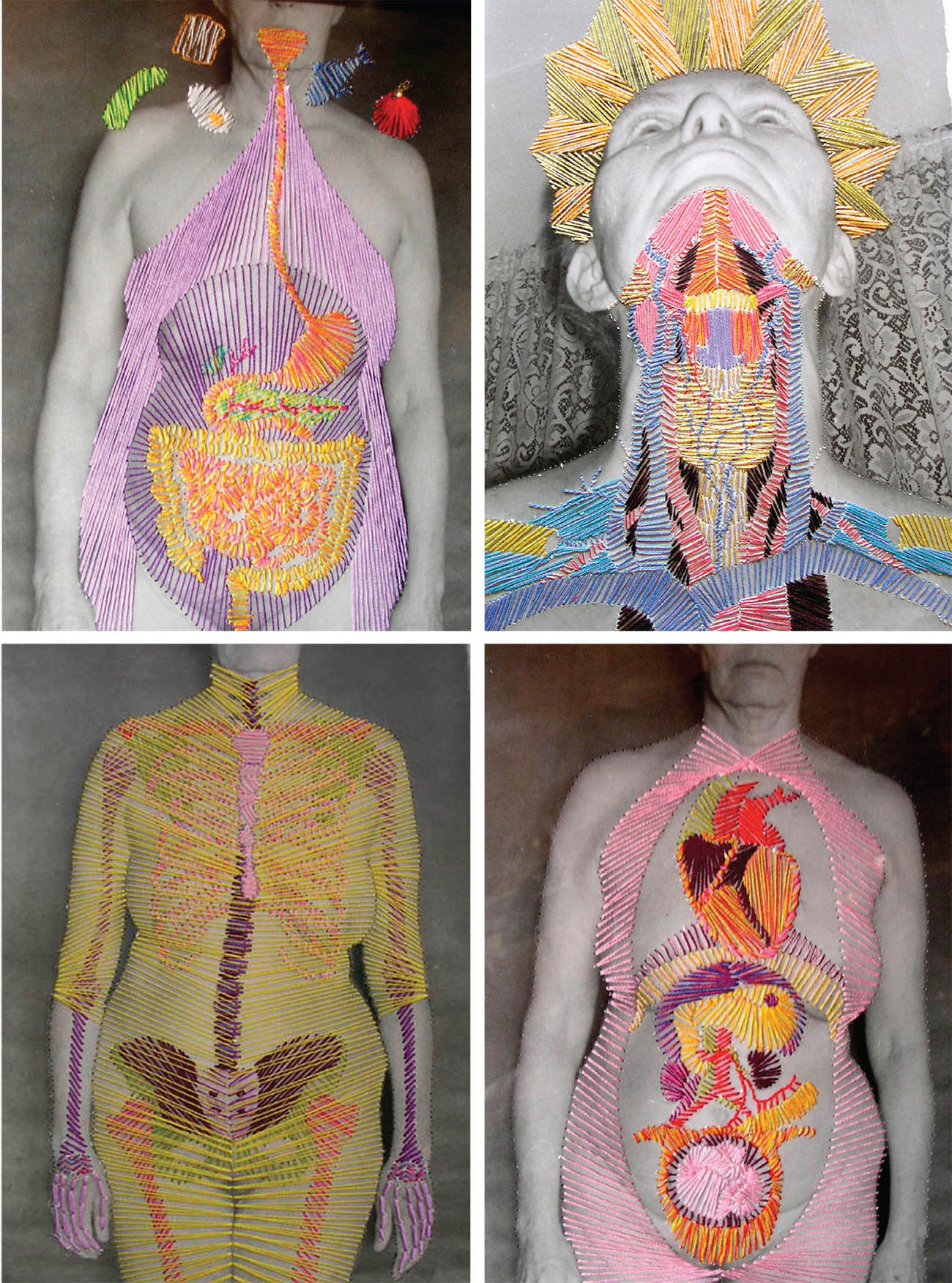

In the late 1990s, Pinky’s sister Frances McCall was in a battle with cancer. She eventually moved in with Pinky at her home in Fairhope, where she was cared for until her death. The tragic experience left its mark on Pinky’s heart but also found its way into her art. “I began to think about how the human body works, how amazing it is,” she says. Pinky studied charts of human biology, traced the lines of veins and arteries, and wondered about its intricate mysteries. The thoughts became stitches on photographs, tracing on the outside what was hidden on the inside. Each colorful single thread becomes an organ or a fetus in a style reminiscent of work by Mexican artist Frida Khalo. Pinky acknowledges the connection, recounting the five years she spent living around the corner from the Frida Kahlo Museum in Mexico City. The daily exposure to one of the 20th century’s greatest artists left a mark on Pinky’s creative aesthetic, inspiring her to push boundaries, but this new body of work where thread and film come together is 100 percent Pinky.

One of a Kind

The portable camper has long since been sold, although the fond memories of using it during her days as an itinerant photographer, and to visit some of her grandmother Lois’s photography locations, still linger. But don’t worry. Pinky isn’t living in the past. She is continually embarking on new adventures of expression, boldly crafting fresh work, and following every unexpected thread, so to speak.

Pinky has mounted more than 40 solo exhibitions, and she has artwork in the collections of numerous museums across the Southeast and the country, including the National Museum of Women in the Arts. She has, through her life’s work, developed a strong voice and recognizable aesthetic that has earned her numerous accolades, including the Mobile Arts Council’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

“If I can look at a photograph and say, ‘Oh, that’s a so-and-so’, by name, then I feel like that person has found their voice, rather than trying to please the public,” she says.

While Pinky has surely created more art than we have pages to discuss, one thing is certain: You’ll always be able to look at each piece and say without a doubt, “That’s a Pinky Bass.”