Uniforms for the Batallon de Morenos, drawn by Jose Nicolas Escaler in 1763. Image courtesy General Archive of the Indies of Seville

During Mobile’s long colonial century (1702-1813), three different European powers ruled the city. After each transition, from French control to British to Spanish, a new ruling class arrived while residents weighed their options. A new government meant new rules. People wondered how their lives might change. If they had means, they could go someplace else. But if enslaved or poor, they usually had no choice in the matter. Mobilians of color had the most to lose and so studied each power shift accordingly. Would new rule provide them any opportunities, or more restrictions, or some complicated mix? As ever in history, there were winners and losers. The lucky few managed to better their situations and even flourish, especially after the Spanish takeover.

Petit Jean and Nicholas Mongoula were two such men. Petit Jean (Little John) was born in French Mobile, probably during the first half of the 18th century. Parish church registers, official correspondence and censuses provide a few facts about him, from which one can extrapolate more broadly as to his daily activities. Records list him as an enslaved “mulatto” who tended cattle. While subject to his owner’s whims like any enslaved person, he was more fortunate than most in that his assigned duty afforded him considerable freedom of movement. He spent long days (and many nights as well) in rural settings tending his master’s livestock and probably carried a gun. He knew how to deter wolves and poachers, how to coax frightened cows out of bogs and how to drive them along to market, and he could kill and butcher them efficiently when called to do so. He would have possessed a thorough knowledge of the surrounding country and likely delivered messages between plantations, sharing news and gossip. He would have known area Indians and probably spoke the Mobilian jargon as well as French. The former was a coastal pidgin language used by the area’s diverse peoples to facilitate trade. His wife, also enslaved, lived downtown.

Petit Jean’s prospects dimmed after the British acquired Mobile in 1763. British slavery was harsher. Royal policy discouraged manumission, something the French occasionally practiced, and forbade Sunday gatherings, feasting and drumming, all popular pastimes among the enslaved that helped ease tensions. Violators were subject to public whipping. Petit Jean now needed a pass to travel beyond two miles. Doubtless he feared for his wife in town. What if she ran a simple errand and forgot to bring her pass? Would the authorities give her the benefit of the doubt and let her go, contact her owner or whip her? He must have considered escape — he could so easily slip into the vast wilderness — but that meant abandoning his wife. And if caught, he faced draconian punishment, perhaps a painful branding.

The American Revolution unsettled Petit Jean even further. In 1780, a Spanish army headed by General Bernardo de Gálvez appeared before the walls of Fort Charlotte and demanded its surrender. Which side should he choose? Petit Jean had no love for the British, but if he helped the Spanish and they lost, he could face a sale and separation from his wife or, worse, execution. Yet there were compelling reasons to cast his lot with Gálvez. The Spanish generally practiced a more easeful form of slavery than the British, with fewer rules, greater tolerance of mixed ancestry and a better chance of manumission. Petit Jean would have seen evidence of this in the 400 free Black and Pardo (mixed-race) soldiers in Gálvez’s ranks. Each man carried a gleaming musket with a bayonet. The free Blacks wore handsome white jackets with gold buttons and sported black hats with red cockades, while the Pardos marched attired in green jackets with white buttons.

This was compelling evidence, and Petit Jean offered his services to the invaders. His knowledge of the country stood him in good stead, and the Spanish made him a courier and a spy. After he completed each task, he got more responsibility. On one occasion, Petit Jean successfully led four men on a dangerous mission. Given his enthusiasm and ability, he soon came to the attention of Gálvez himself, who used him as a personal envoy. After Mobile’s fall, Gálvez sent him to New Orleans with critical dispatches ordering the Spanish commander there to immediately send reinforcements for the upcoming attack on British Pensacola. Petit Jean traveled for days across difficult terrain, delivered the dispatches and returned safely. New Orleans sent reinforcements, and Pensacola fell in the spring of 1781. Petit Jean, an enslaved cattle drover, thus played a small but important role in Britain’s defeat during the American Revolution.

Certainly, Petit Jean gambled that his service to the Spanish Crown would improve his lot. And so it did. Mobile was now part of Spanish West Florida, and the grateful conquerors paid his master $400 for his freedom and helped him free his wife. Petit Jean made all the right decisions during an extraordinarily challenging time. His last appearances in the historical record occur in 1786, when the census listed him as a free man, and two years later when he bought a 76-foot-wide lot on Eslava Street.

Nicholas Mongoula enjoyed more advantages than Petit Jean, but also faced risks in the area’s volatile political climate. Born of free Black parents in French Mobile, probably around 1720, his unusual last name is evidence of the 18th-century Gulf Coast’s cultural complexity. “Mongoula” is a Mobile Jargon term that means “my friend” or “our friend.” Scholars have speculated that one of his parents might have been indigenous and the other Black, a not uncommon circumstance in colonial Mobile. In any case, his parents, and Mongoula too, probably enjoyed close relations with the area’s many Indians.

Whatever the exact circumstances of his birth, the records show that Mongoula was a devout Catholic. He acted as a godparent to at least three enslaved Blacks in Mobile, and the parish register lists his marriage to a free Black woman named Francisco Mimi. They had two children named Santiago and Luisa.

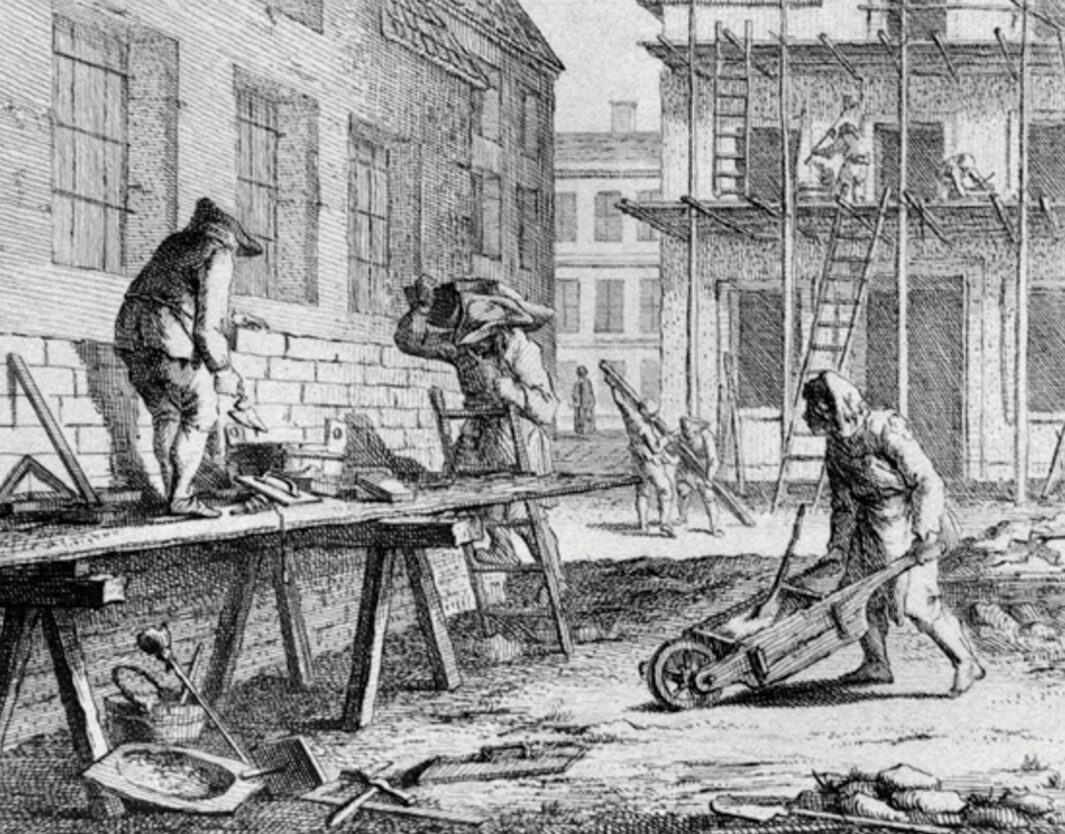

Mongoula’s activities during the Spanish siege of Mobile are unknown, but like Petit Jean, he profited by the result. After the surrender, the Spanish formed a free Black militia and commissioned Mongoula as the captain, clear recognition of his status. When not commanding troops on the parade ground, Mongoula worked as a master mason, his roughened hands troweling mortar onto the era’s thin clay bricks and placing them onto the rising piers, walls and chimneys of Spanish Mobile. Authorities respected his skill, as evidenced when they asked him to inspect repair work on the fort. Not surprisingly, he also owned property and in 1792, sold a house on Royal Street for $36.

Six years later, Mongoula dictated his last will and testament. His earthly possessions included a little cabin in Mobile, some land cultivated in rice, corn and beans, and a dozen head of cattle. He died May 2, 1798, and received full Catholic burial rites. His wife inherited all his property. Son Santiago worked as a carpenter in New Orleans and served as a non-commissioned officer in the free Black militia there. Daughter Luisa remained unmarried and lived at home with her mother.

Nicholas Mongoula and Petit Jean each made a successful life in a rough and confusing world using their smarts and the advantages at hand. Spanish rule allowed each of them to better his prospects. In the process, they helped not only themselves and their families, but their city as well. mb

John S. Sledge is the co-author of “Mobile and Havana: Sisters Across the Gulf” and has produced seven other books of local history.