On December 14, 1944, Tom Galloway turned 21 years old. Galloway, a second lieutenant with the 28th Infantry Division, rarely kept his monthly bourbon ration for himself, preferring instead to turn it over to the men serving beneath him. This month, though, he kept one bottle. “And as it happened, my mother had sent me a fruitcake, mailed it back in November, and it arrived right on my birthday.”

Among the quiet, snow-blanketed trees of Luxembourg, Galloway had a birthday party. Despite the occasion, war was never far from his mind. Galloway unexpectedly ordered an inspection of the guard posts, a command that usually came down from the sergeant. “I think maybe the whiskey was doing a little talking, I’m not sure, ” Galloway adds.

“We went around and checked the guard, and they weren’t challenging anybody! Nothing was happening. It was like Sunday in the park, and we were just waiting for Christmas.” Galloway had his corporal threaten the men with demotions. “So they were on their toes, ” he says. “That was the 14th of December. The morning of the 16th was the first morning of the Battle of the Bulge.”

The surprise German offensive is remembered as one of the most costly battles for the U.S. during World War II, claiming the lives of an estimated 19, 000 American soldiers. Galloway survived the first day’s onslaught, but most men weren’t so lucky. “Sometime the next morning, the first sergeant came to me and said, ‘You’re the only officer I’ve got left.’ I started to say, ‘You stay here, and I’ll go to Alabama.’”

Today, a 91-year-old Tom Galloway sits in his dim living room on a busy Dauphin Street corner. “Are you here to talk to me about how I singlehandedly won the War?” he jokes. Just weeks shy of his 92nd birthday, Galloway’s mind is still sharp as a diamond. He and wife Alma have three sons, nine grand-children and four great-grandchildren. Galloway only retired from practicing law four years ago, and, according to his wife, that was because others convinced him to do so after he fractured his hip. Besides his time in the service and a three-year stint as the assistant attorney general in Montgomery, he has lived in Mobile for his entire life.

Road to War

“We didn’t know you were supposed to have anything, ” Galloway says about growing up in Mobile during the Depression. Compared with the struggles of other families, however, he considers himself lucky. “My daddy was in charge of the lighthouse depot in Mobile, so we weren’t suffering.”

Galloway graduated from Murphy High School and went on to Auburn where he joined the ROTC. It was while a student at Auburn that he first heard of the attacks on Pearl Harbor. Galloway had visited friends in Marietta, Georgia, that weekend and describes his struggle to hitchhike back to school on Sunday. “I had to get to Auburn, and the roads were full of soldiers thumbing and trying to get to their base.

“Pearl Harbor was a world away. I had never heard of it, didn’t know what it was, ” Galloway admits. Even so, the event would have a monumental effect on his life.

During the first semester of his senior year at Auburn, Galloway was sent to Officer Candidate School where he trained as an artillery officer and a forward observer. While stationed at Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina, Galloway caught wind of another historical event that would alter the course of his life. “We heard about D-Day on a Wednesday, and Saturday the colonel called me in and said, ‘Tom, you’ve got to go. You’re heading overseas.’ We were replacements, to tell you the truth.”

ABOVE A photo of Galloway in his military uniform in 1945. “I wouldn’t say you were eager to serve, ” he says of joining the military. “But you didn’t mind serving. Because everybody you knew was in there [the military] one way or another.”

The Great Escapes

Just months after the allied invasion of Normandy, Galloway landed at Omaha Beach, the scene of the most intense fighting during the D-Day invasion. “But the beach was clear. I didn’t get shot at or anything. How in the hell those soldiers ever got up that embankment, I don’t know. ‘Cause I had a hard enough time getting up, and I wasn’t getting shot at!”

Galloway and his 28th Division worked their way through France until he found himself on the Seine outside of Paris. “A buddy and I said, ‘We’re within 20 miles of Paris, and we may never get to see it. We better go on up there and see what’s happening in Paris.’ So we did.”

The recently liberated capital city was in full swing. “That was an eye-opener for a 20-year-old boy, ” Galloway says with a laugh. “Those Parisians are something else. They were celebrating

— the streets were full.” Galloway and his friend stayed in Paris overnight. “[Then we] got on back to get ready to go to war again.” In September 1944, Galloway’s division was the first to cross the border into Germany.

In November, they were sent into the Hürtgen Forest, east of the Belgian-German border. The two divisions that had fought there in the previous month had advanced only three miles and lost 4, 500 men. “Hürtgen Forest was the worst. Absolutely the worst. You don’t hear much about Hürtgen Forest, though, because nobody wanted to talk about it, ” he remembers. Gallo-way’s 28th Division lost around 7, 000 men. “Can you imagine that number? For nothing!”

Galloway struggles to find the right words to describe what he calls the most terrifying ordeal of his life. “You can’t believe the injuries. Trees falling on you … the shells. It was just terrible.

“You’re standing by a tree and all of a sudden a bullet hits that tree. Somebody knows you’re there and just is a bad shot, ” he says. “You gained 100 yards, but you couldn’t go back because the Germans had pulled in behind you.”

Galloway was lucky. He escaped the combat in Hürtgen Forest with frozen feet and minor shrapnel injuries. “I was in the medical tent, and the doctor wanted to give me a shot. I’m scared to death of shots, ” he explains. The doctor told Galloway he wouldn’t get a Purple Heart if he didn’t take the shot. “Well keep your damn Purple Heart, ” he responded. “I don’t want a shot!” Galloway had just survived one of the most vicious battles of World War II, but he was scared of a needle. (He ended up getting his Purple Heart).

Galloway’s wife enters the living room during our conversation. “Have you won the War yet?” she asks her husband of 69 years.

He smiles. “I’m working on it.”

After Hürtgen Forest, Galloway’s unit was sent to Luxembourg, a quiet spot on the warfront where the men could rest after such a tough battle. It was where Galloway turned 21. And it was where the Bulge broke.

Three days after the start of the Battle of the Bulge, Galloway was captured by the Germans. “There was another forward observer … a boy named John Bundy from Illinois. One of my worries was, when Bundy hears I got caught, he’s gonna spread that word all up and down the damn line that, ‘Stupid Galloway got caught.’ I think at that time I was more worried about Bundy than I was about getting caught.” On Christmas Eve, Galloway was led into a barn and greeted by a familiar face. “Bundy had gotten caught, too!” Galloway says, still amused by that story after all these years.

In “The War: An Intimate History, ” the companion book to Ken Burns’ World War II documentary, Galloway describes his time as a POW. “There were about 40 of us in a room. And for heat, each man got a lump of coal a day, which is 40 lumps of coal for a big room, and so that didn’t help much.” Galloway reckons he lost about 50 pounds in just a few months.

He ended up imprisoned in Hammelburg, Germany, and was present during the famous Hammelburg Raid in which the U.S. army attempted to rescue Gen. George S. Patton’s son-in-law, who was imprisoned there as well. Galloway seized the opportunity to escape with two other prisoners. After three days, they “got to a river, and wouldn’t you know, the two I had with me, neither one could swim.” He was captured again. And then he escaped again.

“My buddy and I decided, walking through a forest, that we better take off.” The guards marching his group of POWs were very spread out, allowing Galloway and his friend to sneak off undetected. The pair traveled at night, stealing food, clothes and eating raw potatoes from the fields.

Galloway stumbled upon U.S. troops and reconnected with his unit to their great surprise. With the war in its waning days, he boarded a ship for home.

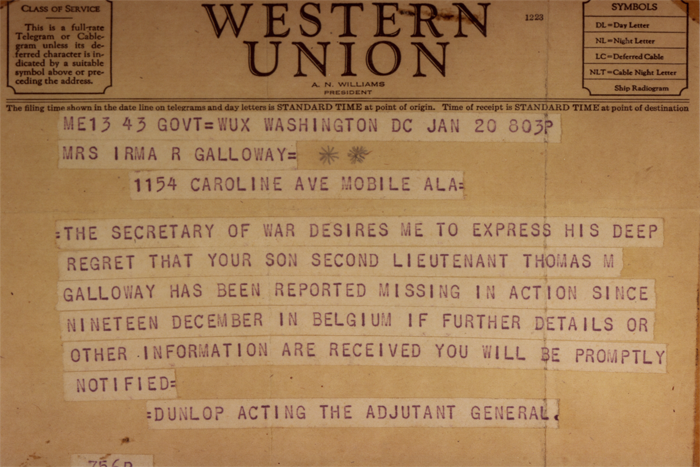

ABOVE Two telegrams received by Galloway’s family report news of his capture in Belgium and his subsequent return to U.S. military control.

ABOVE Galloway admires a collection of relics and articles associated with his time in the service. He says he recognizes his incredible luck in escaping World War II with his life. “I was an exception.”

Against All Odds

Back in the States, Galloway returned to Auburn to get his degree in aeronautical administration before deciding to pursue a law degree at the University of Alabama. After a brief stint in Montgomery as the assistant attorney general, he returned home to Mobile and opened a law practice. Never far from his mind, however, was the thought that he beat the odds.

“I really am lucky, ” he says of his survival of the war. “I have to assume it was prayer. I’m not sure how much praying I did, cause you’re too scared. Later I tried to catch up.”

The grit that carried Galloway through Hürtgen Forest and POW camps still flickers, 70 years after the fact. “You’re gonna make it, ” he says of his wartime mindset. “You had to have that attitude, that you were gonna make it.”

Today just so happens to be Veterans Day. Galloway says he used to go downtown to participate in the Veterans Day Parade, but his condition in recent years has prevented him from doing so. Whether he participates or not, it will be a long time before his city, his nation or his ancestors forget Galloway’s bravery, selflessness and endless fight. Even if he didn’t want that Purple Heart.

text by Breck Pappas • photos by Todd douglas