Did you know Alabama has the largest artificial reef system in the U.S.? It’s true. In fact, we have more than 20, 000 of them. Everything from military tanks to shipwrecks and even airplanes are part of our reef environment. How do they differ from natural reefs, and what purpose do they serve? Let’s dive in and find out.

Real vs. Faux

Natural coral reefs house such a diverse array of aquatic organisms that many marine scientists liken them to miniature underwater cities. Colorful and complex sea creatures like blue starfish and schools of white spotted jellyfish bustle about the reefs, bringing beauty and wonder to an otherwise dull environment. Their importance to the aquatic ecosystem is invaluable.

Reefs provide protection to coastal shorelines and islands by absorbing wave energy. In fact, were they not surrounded by coral, most tiny islands would be wiped out faster than a surfer hanging 10 in a tropical hurricane. More importantly, reefs are home to a vast array of species, the majority of which are sought after by sportsmen or the seafood industry.

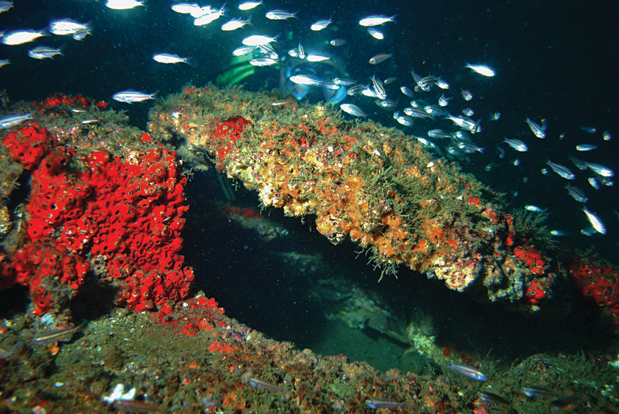

Where natural coral reefs do not exist, artificial reefs can be constructed to promote and encourage the potential growth of marine life, particularly in areas where the ocean floor is generally featureless. This is the case for much of Mobile Bay and parts of Perdido Pass. In effect, these manmade objects and materials serve the same function as natural coral exoskeletons, providing a surface onto which autotrophic organisms, like algae, can attach and subsequently grow while attracting other marine life and a variety of fish species.

The historic Liberty Ships (here, the Allen and Wallace) form humongous artificial reefs, creating the perfect oasis for observing life 90 feet below the surface. Army tanks, such as those at Statler Barge, create some of the best offshore fishing sites in the Gulf. South of Perdido Pass, the reefs known as Rome and Atlantis are formed from bridge rubble. Large structures, such as the Liberty Ships, form interesting shapes for sea life to attach to and explore.

Friend or Foe

Robert L. Shipp, Ph.D. is a professor and chair of the marine sciences department at the University of South Alabama and the author of “Guide to the Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico.” Dr. Shipp also happens to be a nationally recognized expert on the role of artificial reefs as management tools, having testified before the U.S. Congress five times, most recently on the controversies surrounding the population dilemmas of the red snapper. His extensive research has been published in more than 20 marine science journals and various other scientific publications.

“There are a few popular misconceptions about artificial reefs, ” Dr. Shipp says. “Many people believe that they either attract or produce. In actuality, the reefs attract fish, and in a sense, they produce because they have algae. But, we like to look at them more as transformers of the ecosystem. Coral can actually grow on artificial reefs. After 20 or 30 years, an artificial reef practically becomes a natural coral reef.”

Before taking the plunge, each artificial reef must go through a special detoxification process, which includes removing of any fuel lines and any chemicals that could have long-term negative effects on marine life. “In terms of the pros and cons, most of the cons have been eliminated, ” Dr. Shipp adds. “Artificial ones do end up removing some basic marine life, but there’s so much bottom out there that even the little fish aren’t in trouble.”

Into the Deep

Artificial reefs can be made of almost anything you can imagine. In 1953, Alabama became the first state to construct an artificial reef when the Orange Beach Charter Association received authorization to sink 250 automobiles just off Baldwin County. The reef was such a success that over the next few years the state would sink a variable hodgepodge of other objects, including bridge rubble, barges, culverts and even airplanes.

“Special cement pyramids are the most commonly used objects now, ” Dr. Shipp says. “But Alabama did use the rubble from the Dauphin Island Bridge in 1979.”

As Lewis Phillips of Gulf Coast Divers points out, even the Bay’s decommissioned offshore oilrigs now serve as artificial reefs. “Right after the BP oil spill, there was an immediate response from people wanting to pull the rigs. But they’re such a huge part of our marine ecology because there are so many fish there. Decommissioning the rig, but leaving the structure was ideal.”

In 1987, Alabama’s Marine Resources Division cut a deal with the U.S. Army to start sinking decommissioned M-60 tanks. The first six were sunk that year. Since 1994, more than 100 tanks were submerged off the Alabama coast. (See box at left for stats on two of them.) As a result of these and other artificial reefs, Alabama now has the highest rated offshore fishing grounds for red snapper ranging from 15 to 25 pounds. In fact, today, almost 40 percent of all red snapper caught in the Gulf are hooked off Alabama's shores.

Perhaps the most famous of Alabama’s artificial reefs are the Allen, Sparkman and Wallace, located between 8 and 11 nautical miles from Perdido Pass. They’re the shining stars of Mobile’s reef system and go by the collective title of the Liberty Ships. At roughly 441 feet long and about 50 to 60 feet wide, they dwarf other area reefs. The first liberty ships were sunk in 1974 in five separate locations off Mobile and Baldwin counties.

“They’re famous because they’re so big, ” Dr. Shipp says. “You can locate them with even the most rudimentary technology. Divers go there to see the biota, fish life and corals that form on the reefs.”

All sorts of aquatic life make their homes in both real and artifical reefs. Directly in front of Bahama Bob’s Beach Side Cafe in Gulf Shores, Whiskey Wreck, a 200-foot sunken rumrunner boat, is an ideal dive site for beginners.

Day of Wrecking

The artificial reefs are equally enticing to divers as they are to fishermen. And the LuLu, the newest project by the Alabama Gulf Coast Reef & Restoration Foundation, may not be the biggest, but she’s certainly the coolest. The 271-foot retired cargo ship was sunk in May of last year about 17 nautical miles south of Perdido Pass in Orange Beach. The exterior of the ship sports dozens of sponsor logos painted by Orange Beach-based artist Nick Cantrell, making it one of the more visually attractive reefs along the Gulf Coast.

David Walter, of Walter Marine, was directly involved in the sinking of the ship, an event that was open to the public.

“I didn’t use explosives, ” Walter says. “The secret to properly sinking a ship [without explosives] is to get water into every compartment. You have to time everything just right. Leaving air in a compartment will cause the ship to turn on its side, which destroys its value as a diving reef. We cut a hole at the back of the boat at the waterline and cover it with plywood and sealer. Then, for the sinking, we take it off. As the ship sinks by the stern, you want the compartments to fill

up equally.”

After being swallowed up by the sea, the LuLu made a 16-minute descent to 145 feet below the surface with the top of the ship leveling off at a state-required 60-foot clearance. She is now Alabama’s first whole-ship artificial diving reef.

The Alabama Gulf Coast is by far the leading location for both observational and recreational reef diving. And while you may not be ready to brave the ocean depths just yet, you can at least say that you learned a thing or two about our reef system. (And you didn’t even have to hold your breath.)

The Liberty Ships

SIZE

Weight: 14, 245 tons (displacement tonnage, not actual weight)

Length: Each ship is roughly 480 ft. long.

Width: 75 – 80 ft. wide

LOCATIONS

Allen reef: 95 fsw / 8.40 N.M. from P.P.

Sparkman Reef: 90 fsw / 18.43 N.M. from P.P.

Wallace Reef: 90 fsw / 10.93 N.M. from P.P.

PURPOSE Public diving and fishing; observance of aquatic life by marine scientists

FUN FACT The Liberty Ships are referred to as “ghost-fleeted” ships, meaning that they were reserve fleet naval vessels that were fully equipped for service, but not needed and therefore classified as decommissioned. See page 84 for more about the history of these ships.

Lawrence Sims Reef and Frank Broz. Reef

SIZE of one m-60 tank

Weight: 50.7 short tons (45.3 long tons)

Length: 6.946 meters (22 ft. 9.5 in.)

Width: 3.631 meters (11 ft. 11.0 in.)

Height: 3.213 meters (10 ft. 6.5 in.)

LOCATIONS

Lawrence Sims: 29.51 N.M. from P.P.

Frank Broz: 29.22 N.M. from P.P.

PURPOSE Offshore fishing

FUN FACT The primary aquatic life here is red snapper. Melvin Dunn of Theodore currently holds the red snapper state record: 44 lbs. 12 oz.

From left to right: The Lulu on the day of sinking, one day later and three months after sinking.

The Lulu

SIZE Length: 271 ft.

LOCATION Roughly 17 nautical miles south of Perdido Pass

PURPOSE Recreational diving reef open to the public

FUN FACT For the sinking of the ship, Mac McAleer, of LuLu’s at Homeport Marina, arranged for the Wet Willie Band to perform on the barge. This was the first time a band had been provided for the sinking of a ship since the Titanic.

text by Joshua D. Givens • photos by Lila Harris of Aquatic Soul Photography