Six years ago, journalist Lynn Oldshue set out to write a story about bus riders in Mobile.

“The first time I rode the bus, I feared rejection,” she remembers. “Instead, riders scooted over and made room for me.”

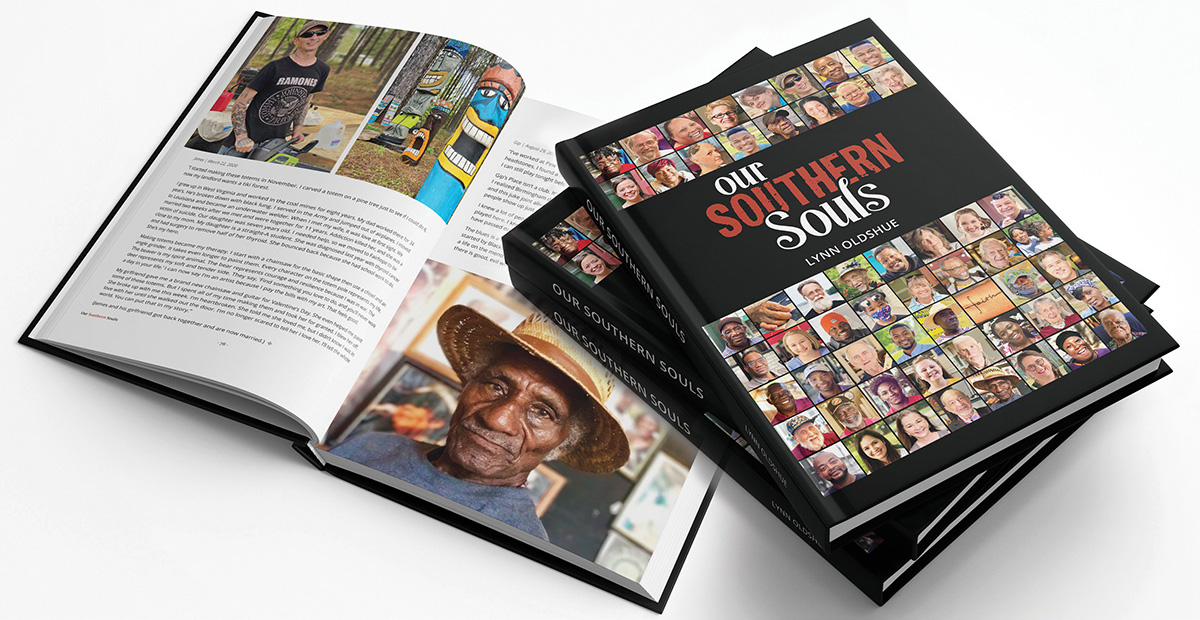

It began a profound, months-long experience for Oldshue — riding the bus and collecting the heartfelt stories of her fellow passengers. When her husband bought the book “Humans of New York,” filled with the stories of random New Yorkers, Oldshue was inspired to create Our Southern Souls as a website and Facebook page where she could post profiles of everyday Southerners. Now, in a book of 177 captivating profiles, Oldshue shares true tales of triumph and heartbreak in our own backyard.

Where did you pick up your love for people’s stories?

I’m a reader and a listener. My family published newspapers in Mississippi, and I grew up in Yazoo City in the shadows of Mississippi writers Willie Morris and Eudora Welty and storyteller Jerry Clower. I always dreamed of being a writer and telling people’s stories, but it took a long time to get here.

How did this book come about?

People started asking for a book, but it never felt like the right time. That changed last December. Some of the World War II veterans, civil rights activists and older Southerners that I interviewed started passing away. I spoke with Katherine Phillips Singer days after I posted her story online, and she said it was the last time she would tell her story. She died two weeks later. Their stories are our history, and I want to help pass them down. I owe a lot of credit to Jodi Engel who designed the book and really created something beautiful.

Where did you find your subjects?

Everywhere. Most of them are people I randomly walk up to. These are the people all around us: at the Fairhope Pier, on Dauphin Street, taking your order, walking past you on the sidewalk, or in line with you at the grocery store.

Did you learn any tricks to approaching a stranger and engaging them in conversation?

I usually walk up and say, “I have a crazy question for you.” I show them some of the stories from “Souls” so they know what they are getting into. “Souls” works because I approach each person with warmth and kindness. I care about them from the moment I meet them.

Someone listening with real interest is rare these days, and it feels good when it happens. We all want to know our lives and our stories matter.

You write in the book’s intro, “Whatever I predict their story might be, I am wrong every time.” Is that part of the reason you wrote “Our Southern Souls,” to remind us to challenge our everyday assumptions about people?

At the beginning of “Souls,” I had to unlearn a lot of habits, such as making assumptions about people — especially strangers. My brain naturally categorized them and inserted my own narrative, often concluding they weren’t special or worth my time and attention — even though I knew nothing about them. I was wrong. Everyone has a story worth hearing, and you can’t judge a book by its cover. Six years and 1,800 stories later, people still surprise me every time.

Who provided you with the biggest surprise?

Every story has a surprise. Every one of them. I am still surprised how personal and deep these conversations go in a short amount of time. Some of the best conversations I’ve had are with people I only met once.

Do you think there’s a healing power to sharing your story with another person, and did you ever witness such healing while working on this book?

I believe in the healing power of stories. Most interviews cover some of the hardest parts of their lives. A shift often happens after they talk through the past out loud and let it go. One woman told her story for the first time, and after she finished she said she could see in color again. Faith’s story in the book is the first time she spoke about her abusive husband. It was hard and she was anxious, but it was followed by the freedom of releasing fear, guilt and shame. She went back to school and finished her degree in counseling to help other women.

The healing power of stories requires a good listener. Each of us can give that to someone else.

You’re donating all proceeds from book sales to the United Way of Southwest Alabama’s Pledge Project. Can you tell us about that project?

For me, conducting the “Souls” interviews and writing stories for Lagniappe about sex trafficking, poverty and domestic violence opened my eyes to the vulnerabilities in our community and what people do to survive. There are great programs like Big Brothers Big Sisters and Dumas Wesley providing solutions in Mobile, but they are limited by funding and have waiting lists for people who need their help. The Pledge Project began in 2020 to raise money to get 2,020 kids off these lists and into programs they need.

The book is dedicated to your yellow lab Rosie who you said was by your side during the entire writing process. It’s only fair to ask — how do you think Rosie would describe her own life story?

Rosie was an emaciated puppy when my nephews found her in a box in the woods. They gave her to us when we moved to a farm with acres to roam. She went from discarded and unwanted to two homes where people love and care for her. She gives that love and comfort right back, putting her head on my leg or moving closer when she hears my frustrated voice talking or cussing to myself when I can’t get the words right.

She always looks like she is smiling and happy right where she is, and she calms me down.

Where can readers buy “Our Southern Souls”?

In Fairhope, it’s for sale at Page & Palette and Melt & More. In Mobile, it’s at The Haunted Book Shop and Ashland Gallery. You can also order it online here.

Excerpt from “Our Southern Souls”

Bathon

“I’m the kitchen manager at Five restaurant on Dauphin Street. We give out 70 to 100 free lunches on Thursdays to anyone who wants to eat. A portion of our sales at the restaurant goes to American Lunch, so we can afford to do this. At the end of the day, the restaurant also gives our leftovers to the homeless and hungry instead of throwing them away.

My mom taught me that it is not what you receive, it’s what you give. The blessings will come. My mom and grandmother taught me how to cook, and I picked it up along the way. My grandmother said, ‘If you know how to cook, you don’t have to depend on a woman.’ I’ve been cooking for 13 years. One day I want to own my own restaurant.

I know what it’s like to be in a difficult situation. We have three daughters. Our daughter, Camille, was diagnosed with cancer when she was 3. She passed away a year later on April 29, 2017. We were at St. Jude’s in Memphis for more than six months. We stayed at a Ronald McDonald House for a while. People cooked and cared for us. They became our family away from family. Watching children battle cancer with smiles on their faces made me realize there’s no reason to go through life with a frown. Camille lives on through us in everything we do. My tattoo says, ‘Family over everything.’ That’s how I live my life.”

Sahar

“I grew up in Iran and lived there for 27 years. I am Baha’i. We believe in peace, love and living in harmony, no matter your background or religion. Iranians don’t recognize us or give us our basic human rights. In school, I was called names and treated like I was dirty by teachers and students. I passed the test to get into the university four times, but I was never accepted. Being a woman and part of a minority religion, I was persecuted all of my life. I was like a caged bird.

As a woman growing up in Iran, the traditional thinking is that you are no one until you get married and become someone’s wife. But I was very independent. At age 18, I moved to Tehran with my sister and started working. We needed our father’s approval to do this. A woman can’t leave the country without permission from a father or husband.

Women are raising their voices and showing who they are, but men still dominate the culture. If you wear boots or jackets, you are dressing provocatively to men and have to pay a fee. I was arrested for an outfit I wore. I love to dance and teach Zumba. I couldn’t do that in Iran because it was provocative towards men. But men touch you on the street, and it’s not safe. I was sexually abused in the workplace when I was an 18-year-old intern. I couldn’t report it or take action because they would say it was my fault. It is hard to grow up in a world like that.

My sister and I left Iran in 2010. We went to Turkey and applied to enter the U.S. We didn’t have a sponsor, so we were sent to Mobile as refugees. We didn’t know anyone here. We didn’t know the language, the culture or what to do. Catholic Social Services helped us when we arrived. The first two years were hard. I went to school and graduated with honors. I used Google Translate to get me through.

I am not sad about my past. It is what makes me a fighter and survivor. People can’t stop you. Your culture can’t stop you. Sometimes you have to move away to make a change. We have to show a better way to the next generation. My best voice is art, and I want to make people think and open their eyes.”

Jeremy

“I started Cops for Kids because I want kids to understand that police officers are human. We like to have fun and are approachable. When I talk to kids in schools, some tell me about a family member in jail or that a police officer came to their house the night before. I want to give kids a lighter side of what we do. I let them sit in the police car and turn on the lights and sirens. I also give them stuffed animals and police badge stickers.

I love seeing some of my kids from the elementary schools in my area at Mardi Gras. My spot is at the corner of Royal and Dauphin streets. I started doing fun things with a mask that fell off one of the riders. Kids wanted to high-five and take pictures — it escalated from there. One officer escorting a band started dancing when they got to my corner. I thought, ‘Heck no. There’s no way he is doing that on my side.’ We had a dance-off, and my dancing started from there.

Mark Zuckerberg stopped by Mardi Gras last year during his tour of the states. He stood at my corner, and I said to him, ‘This may be a stupid question.’ He grinned and said, ‘I am.’ He asked me to keep it quiet because they were just here to have a good time. I had my picture made with him.

At least 200 officers work each parade, and there is an officer at every intersection. We are tired and cranky by the last two days, but we’ll still kick it around a little bit.”

Donna

“I’m 48 and just got my high school diploma. I finished with a 4.0 GPA. Math and science were the hardest parts, and I got help with those. One of my daughters is going back and getting her diploma because she saw me do it.

At 16, I got pregnant and dropped out of school. I wanted to go back, but one year turned to two, and two turned to three. At 48, I was fired from my day care job because I didn’t have my diploma. If he hadn’t fired me that day, I never would have gone back to school. Now I want to be an X-ray technician.

It’s hard to find a job that works around my pain. When I was 25, I was shot in a drive-by shooting in Prichard in 1996. They shot three people that night. I’m terrified of doctors, so I didn’t go to the hospital. I didn’t know my intestines were twisted from the shooting. After I got pregnant, the doctors had to untwist them. I lost the baby.

My son had just turned 20 when he was incarcerated for murder. He’s in for 25 years. He was going the wrong way and probably wouldn’t be here today if he wasn’t in jail. I’m trying to get him on the right path. I want him to have his head on straight when he gets out. I worked three jobs when my kids were young: a day care, Goody’s department store, and a cleaning job. I didn’t have enough time to raise my kids. My son got out of hand. I feel guilty about that, but I was doing the best I could to pay the rent and buy food for my kids. I advise anyone to stay at home with their children.

My oldest daughter struggled in high school but put herself through college. My 12-year-old daughter keeps me going. Both of my daughters inspire me to do better. My Mama taught us if you do something right the first time, you won’t have to do it again. I hope my kids learn that lesson from me.”