In 2025, the last furniture store on Dauphin Street liquidated its stock and closed its doors. Hoffman Furniture Company was first listed at 411 Dauphin Street in the 1933 city directory. In that year, it joined a dozen furniture retailers on Dauphin Street between Joachim Street (Gulf Furniture Co.) west to Warren Street (International Furniture Co.).

Even with the Depression worsening, Mobilians would have had a good selection of home furnishings by strolling down the city’s busiest retail district. It had not always been that easy.

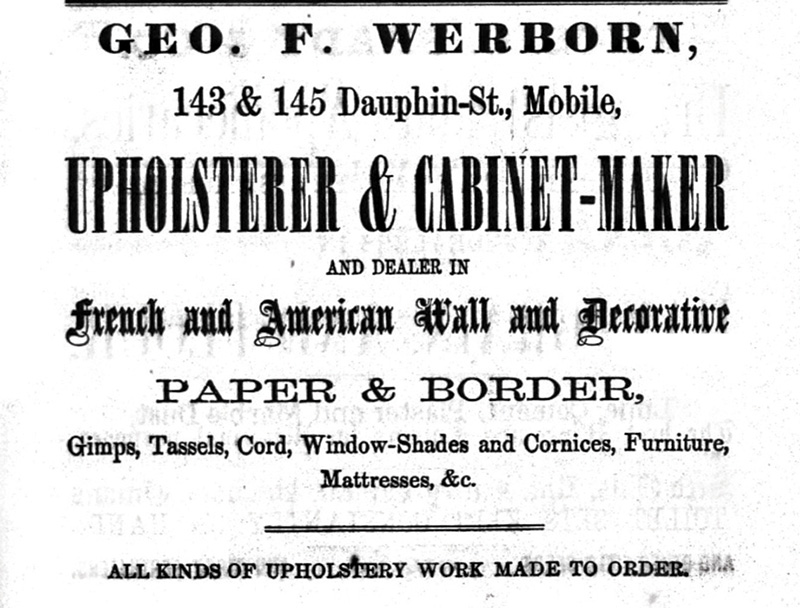

There were no furniture stores in Mobile prior to the Civil War. In 1860, there were four cabinet makers, just two of whom were operating on Dauphin Street. Furniture was made to order, and it was pricey.

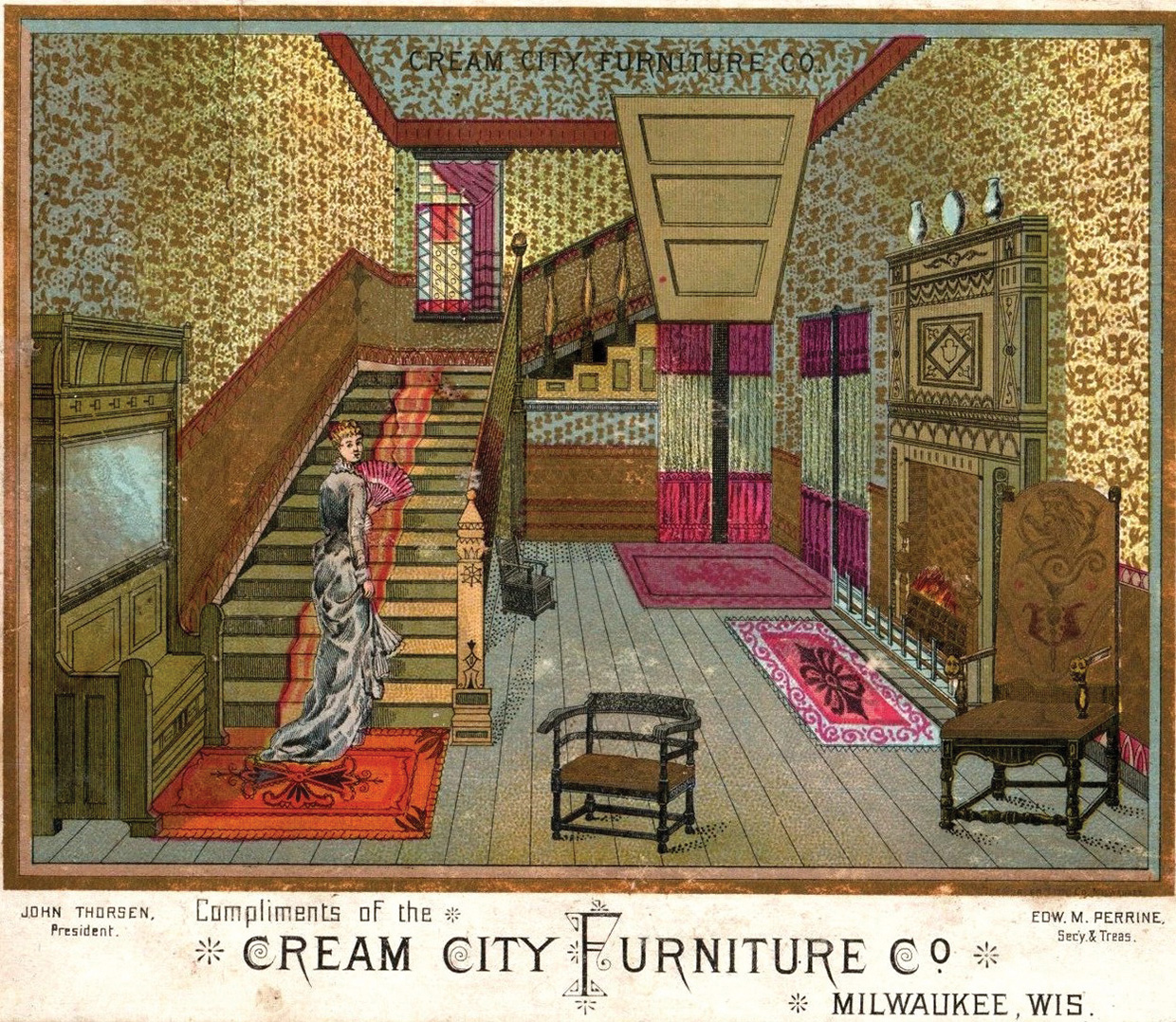

Industrialization following the war, increased the production of everything, including furniture. This brought down the prices and made it increasingly affordable to a growing middle class. Retail furniture stores sprung up in American cities at a rapid pace.

According to Mobile’s 1870 directory, the city had 11 retailers. The majority were operating along Water Street although one of the former cabinet makers, George Werborn, was offering ready-made furniture at 143-45 Dauphin Street.

By 1878, Adam Glass who had immigrated from Germany in 1869, had opened his first furniture store at 40 Dauphin Street after working as a carpenter and cabinet maker for another Dauphin Street dealer. By 1885, he advertised himself as a “Manufacturer and Dealer in Furniture.” The “manufacturing” may in fact have been the assembling of parts manufactured elsewhere.

Glass would go on to construct the city’s grandest furniture emporium on South Royal Street around 1890. Those who could not afford to shop his luxurious “furniture, rugs, carpets, tapestries and curtains” had plenty of less expensive options.

By the start of the nineties, there were 14 furniture dealers in town, and Dauphin Street was growing and extending west as the main business district. German-born Ferdinand Bitzer was offering his wares at 409 Dauphin while the Mobile Furniture Co. was open for business jut to the east at 405-07.

Frank E. Tutwiler advertised heavily in newspapers in counties north of Mobile alternating between proclaiming to be “The Cheapest Furniture House in Alabama” to its “Finest.” Here customers could select from “Stoves, Lamps, Crockery, Clocks, Paintings, Mattresses and Household Goods.”

Tutwiler’s location was not Dauphin Street but rather on the “four corners of St. Emanuel and Conti.” Sadly, no photographs could be found.

The first of a chain of furniture stores was Rhodes Furniture, which ultimately operated at 401-403 and 405 Dauphin Street. That chain claimed to have originated the installment plan as an option for buying furniture.

The installment plan was created in the 1850s, not for furniture, but for the sale of Singer sewing machines. It was a huge success, but the idea was slow to reach other merchants. But it eventually did.

The Hoffman name, so long associated with both furniture and “Cheerful Credit” would not appear in Mobile’s city directory until 1909, when Milton Hoffman was listed as offering “Cleaning & Dying, Clothes Cleaner, Presser.”

His address was then 514 Dauphin Street, near Lawrence Street, an address recently vacated by a man named John E. Fowler. Fowler’s occupation was given as “Sewing Machine and Clock Repairer” but he will go down in the city’s history for possibly building the first airplane in the country.

Less than a decade later as World War I was coming to a close, there were 18 furniture stores on Dauphin Street stretching from Phillips furniture Co. at #261 to C. W. Peters & Co. at #601. The majority were bustling for customers in the #400-500 blocks.

As the next decade roared, a change came over consumers and merchants. Production of automobiles and consumer goods such as radios and furniture boomed.

Hollywood portrayed a lifestyle previously unknown to the average American but an explosion of the installment plan could suddenly make it a reality for them. Why save up for a new car or radio when you could enjoy it for a little down and easy installments? The result was an explosion of consumer credit that would help lay the groundwork for the 1929 stock market crash.

According to Mobile’s 1929 city directory, there were a staggering 16 assorted furniture stores on Dauphin Street alone. Typical of the advertisements was one from the Whitcomb-Carter Furniture Co. at 413 Dauphin Street. Consumers were invited to use “The Easy Way” offering the “Lowest Prices and the Easiest Terms Ever Given.”

Typical of ads in the 1920s was one for Monk’s Furniture Co. which enticed customers into their store as “A Good Place to Trade – Liberal Credit.”

In 1929, the Webb Furniture Company offered a Jackson-Bell Radio “installed with a first class antenna, $69.50” offering terms of “$5 down and $1.50 per week.” To put that in perspective, in today’s dollars that would equate to a $1,350 radio with $97 down and $30 per week.

With the stock market crash and growing unemployment, workers could not always meet the payments on their furniture, radios, refrigerators and cars.

In November of 1931, a partner in the Edwards Brothers Furniture Co. located at 558 Dauphin Street was hauled into court after arriving at a customer’s house and demanding payment. When he did not receive it “he entered the house, stripped the curtains off the window and took them back to the furniture store.”

Judge David Edington admonished the unhappy merchant with this: “You can’t walk into a person’s home and carry off anything without the person’s permission. If you want those curtains, go to superior court and secure the proper legal rights.”

The judge then ordered him to return the curtains within 12 hours.

As the decade progressed, more than one furniture store added a second address nearby which they called their “Exchange.” While some termed their offerings there as “Wonderful Used Furniture Bargains,” others were more specific in describing the contents to include “Exchanged, Repossessed, Used Furniture and Radios.”

Two furniture stores opened on Dauphin Street in 1933, one new, one relocated. Nathan Furniture Co. announced a new store at 400 Dauphin Street and that was the first time Morris Hoffman’s business had been listed as a furniture store.

Mr. Hoffman had been located at 510 Dauphin Street where his business is alternately listed as “dry goods” and “clothing.” Around World War I, he moved into Louis Noble’s former grocery business at 411-13 Dauphin Street with his family residence upstairs at 413 1/2. This would be the address associated with the Hoffman name for over a century.

The 1931 and 1932 directories list Hoffman as running a “department store” at this address. And then in 1933, number 411 Dauphin Street is first listed as “Hoffman Furniture Co.” and “Department Store.”

By the late 1930s, Hoffman Furniture advertised two specials. The first was a package deal for the kitchen which included “a 4 burner oil range, a 5 piece breakfast suite, a utility cabinet, an 18 piece dinner set and a 7 piece ice tea set.” All for $39.50.

For an additional $20, Mr. Hoffman offered a “14 piece bedroom outfit with poster bed, vanity and bench, chest, a 50 lb mattress and wire spring frame, 1 bed lamp and two boudoir lamps with boudoir lamp shades.” In addition he included “2 feather pillows and a silk bedspread.”

He advised Mobilians: You can’t save money unless you shop Hoffman’s first!

In ads running in December of 1940, Mr. Hoffman was offering portable oil heating stoves and his ads then advised: Let our cheerful credit plan bring warmth and comfort.

During World War II, as shipyard workers flooded the city, the number of rooming houses and “furnished rooms” exploded and no doubt the landlords were able to find lower-priced furniture along the western portion of Dauphin Street which merchants assured their customers was “out of the high rent district.”

A 1942 advertisement for Hoffman’s advised “Our Exchange Department Has Some Wonderful Used Furniture Bargains.” The bargains ranged from a cedar chest at $8.95 to a Coldspot electric refrigerator for $59.50.

The war’s end eventually prompted an economic boom for merchants following years of rationing. The number of retailers offering kitchen and laundry appliances increased. The GI Bill allowed countless returning vets to build a home and all those new homes needed furniture and appliances.

In 1946, a dozen furniture stores offering a selection of both furniture and appliances stretched from the National Furniture Store at #225 to Dyess Furniture out at #600. Hoffman’s joined at least four other furniture retailers in the 400 block.

Coleman Furniture and Mattress Co. at #466-68 offered furniture for the “Living Room, Dining Room, Kitchen and Den” while offering the ability to make old mattresses new. Rhodes-Perdue was offering “Kroehler Living Room Suites and Philco Refrigerators and Radios.”

With all that construction going further to the west, it was inevitable that the retailers of just about everything would follow. As early as 1950, Abraham Gardberg had moved his furniture store to what was then the city limits: Florida Street.

By 1965, two furniture stores were listed out on Government Boulevard and a recently named Airport Boulevard. The shift was even more apparent by 1970. Although some 15 furniture stores remained downtown, four were already on Airport Boulevard and the newly constructed Beltline Highway had three more.

Six years later, additional furniture stores were on those streets as well as Dauphin Island Parkway and out in Tillman’s Corner. Meanwhile, downtown Dauphin Street had become largely a sad array of vacant buildings. West Mobile was closer to a majority of residents and retailers offered unlimited parking.

The 1995 city directory listed three furniture stores on Dauphin Street, each easily dwarfed by a single competitor west of the Beltline. And finally, in 2000, it was down to the last furniture store on Dauphin Street: Hoffman’s.

In 2025, the Hoffman family sold the last of the inventory in a building which had not only been their business, but which had been their home for a generation. The property which stretches south to Conti Street as well as east to North Franklin and west to South Hamilton has been sold.

The buyer, whose LLC is named Friendly Credit, is not sure what his final plans are for the buildings once they are restored. But he plans to respect the Hoffmans’ long legacy at the location and refurbish that iconic sidewalk sign.