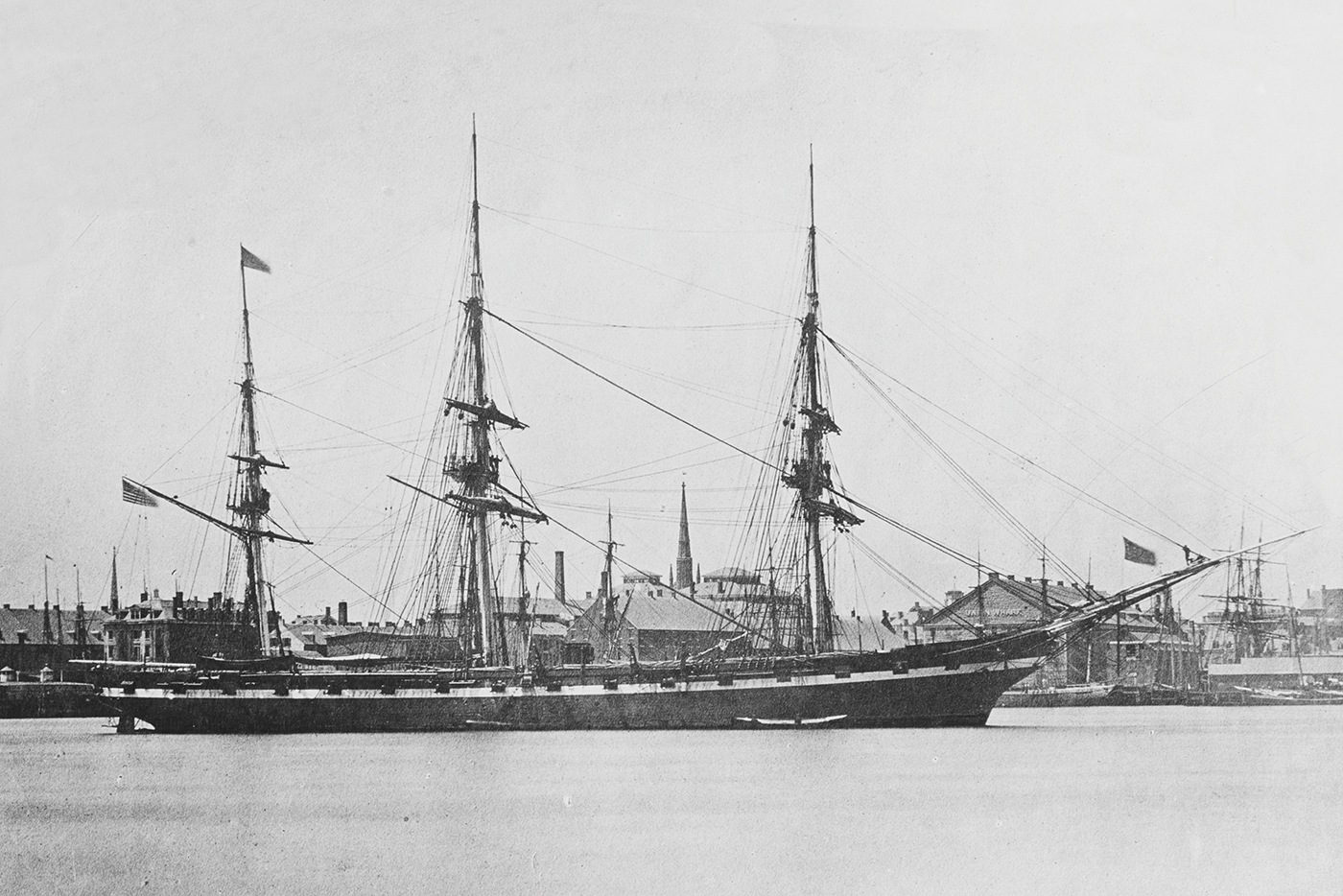

Above USS sloop-of-war Hartford looking lean and mean during the Civil War. Courtesy Naval History and Heritage Command

It was an ironic turn to be sure, the kind history sometimes presents along its meandering course. During the early 1950s, a small group of Mobilians did everything in their power to save the USS Hartford, the very ship that their forebearers almost 90 years earlier did everything in their power to destroy. The formidable steam sloop that carried Admiral David Glasgow Farragut and his valiant crew past Fort Morgan amid a storm of shot and shell in the summer of 1865 was, by the end of World War II, a rotted hulk taking up valuable harbor space in Norfolk, Virginia. The Navy asked Congress for permission to scrap the vessel, and that is when a clutch of Mobile leaders petitioned instead for her restoration and transfer down to the Highway 90 Causeway as a floating museum.

Not surprisingly, Alabama congressman Frank Boykin enthusiastically endorsed the idea. On June 24, 1954, he appeared before the Senate Armed Services Committee for a hearing on H.R. 8247, “An Act to provide for the restoration and maintenance of the United States ship Constitution, and to authorize the disposition of the United States ship Constellation, United States ship Hartford, United States ship Olympia, and United States ship Oregon and for other purposes.” Each of these vessels boasted a distinguished service record, and numerous other individuals were there to advocate for one or another of them (of these the Constitution is now on display at Boston; the Constellation at Baltimore, the Olympia at Philadelphia and the Oregon scrapped). When Boykin’s turn came, he introduced Mobile businessman James B. Donaghey, who owned a successful plumbing and air conditioning business.

Donaghey informed the committee that he was the Grand Knight of Mobile’s Knights of Columbus, and they wanted the Hartford restored and displayed on Mobile Bay. He added that he bore proxies for local chapters of the American Legion and the Veterans of the Spanish-American War. Alabama senators Lister Hill and John Sparkman backed him too, and so informed their colleagues by letter. Sparkman called the Hartford an “instrument of American destiny” and deemed her preservation “morally and patriotically mandatory.” Donaghey delivered a lengthy and carefully researched statement to the committee, arguing that the Hartford’s display on the Gulf Coast would not only teach a compelling history lesson but also operate as a valuable Cold War stratagem. Such an effort, he argued, would stand “as proof to the forces of communism and our enemies of the love of all Americans for this great country of ours. We know that our enemies seize upon any opportunity to create strife within our ranks and having this vessel as a monument of goodwill to the once-divided North and South is cheap at any price.”

Donaghey explained that heavy Causeway traffic and tourism would easily offset the estimated $2 million restoration and transfer costs. “Briefly,” he said, “this plan involves having the USS Hartford berthed at Mobile, Ala., in Mobile Bay, at the site of a new State-owned Park and recreation center within 100 yards of the main highway.” Gray Line Tours projected likely visitation at 2.4 million per annum. An admission charge of 25 cents for adults and 10 cents for children would generate “a minimum annual revenue … of $4,080,000.”

Back in the Port City, the idea of displaying a Yankee warship on Mobile Bay stirred mixed feelings. For its part, the Press-Register loved the idea. “Bring on the Hartford,” it declared. “The Register hopes that the effort to save the famous old naval vessel from the junkyard will succeed. … It deserves to live in the place where it helped make history: Mobile.” Others were less enthusiastic, including members of the United Daughters of the Confederacy. One centenarian, who claimed to have witnessed the Battle of Mobile Bay in her youth, fumed, “They’re not bringing that awful ship back to Mobile.”

Impressed by Mobile’s lobbying effort, Congress gave the city the ship, provided it could move her within a year. That proved a tall order. Those with firsthand knowledge of the Hartford’s condition were pessimistic. Admiral B. E. Manseau, deputy chief of the Bureau of Ships, told the committee she was “most unseaworthy, requiring inspection at frequent intervals.” Her masts, spars and rigging were gone, he reported, and her hull “housed over so that it bears only a slight resemblance to the original Hartford.” More seriously, her rotted planking leaked so badly that pumps had to run around the clock to keep her afloat. He doubted she could even get into drydock without coming apart.

While the ship continued to deteriorate, Boykin, Donaghey and their allies tried to secure funds, but progress was slow. Congress’ mandated deadline passed, and other cities, including New Orleans and Hartford, Connecticut, tried for the ship. Exasperated, the Navy again asked permission to scrap her. Fate intervened, when on the night of November 20, 1956, her pumps failed and, despite attempts to get them working, she listed and sank 30 feet onto a muddy bottom. Crews later raised the wreck and cut it apart before inflicting the final indignity — burning the keel.

A few items of the once-mighty vessel still survive. The bell is on display in Hartford, some guns in California, a rowboat in Georgia and, locally, an anchor at Fort Gaines on Dauphin Island. For the rest, Hartford lives on in blueprints, photographs, eyewitness accounts and in Farragut’s immortal words, “Damn the torpedoes!”

John S. Sledge’s “Mobile and Havana: Sisters Across the Gulf” with coauthor Alicia García Santana and photographers Chip Cooper and Julio Larramendi will be published March 2024.